Hi Quartz members,

Reading a great writer is like watching Fred Astaire dance—it looks almost laughably simple until you try to do it yourself. You don’t have to be a professional writer to need to know how to write; these days there are seemingly infinite outlets for the written word, from a work memo to a Facebook post, from an admissions essay to a public Substack. It’s easy to feel under-equipped to write for these different formats and audiences. Thinkpieces aplenty insist that Americans can’t write; some even claim that writing can’t be taught.

But writing is a skill like any other, which means anyone and everyone can sharpen it with a little practice and guidance. In this email you’ll find advice from our newsroom of professional writers and editors, which can hopefully inspire you to seek out the practice and feedback components. Writing is a journey that no one, even professionals, feel they ever totally master; progress comes from developing your own voice and watching the thoughts on the page better reflect what was originally in your head.

How you know where to improve as a writer

I wish I could write like that. Being an intentional reader and listener is one of the keys to developing as a writer. If you’ve ever found yourself pausing at a turn of phrase or description in a magazine article, podcast, hell, even reading a tweet or ad copy—write it down. It’s a great way to find inspiration.

Perhaps the person used a powerful quote, played with grammar, or had a compelling description of something mundane. Or perhaps it was the way they held back—by using sparse language or a simple, short sentence. When your brain sends a signal that something is interesting, listen to it. Make a note of it. Then, try to weave some of that into your own writing as an exercise.

It can often feel overwhelming to tackle the myriad ways you can become a better writer. But sometimes the smallest change can have the biggest impact. At Quartz for example, we value brevity. Our style guide reads:

“A story should have something clear to say; say it as concisely as possible; use creative ways to get its point across better and faster; not promise more than it delivers; and provide something useful to take away. Respecting readers’ time influences everything: How you write, how you link, how you use images and charts, and what you choose to include—and exclude.”

When I first read those words, and the resulting sharp, powerful prose of the author, co-founder Gideon Litchfield, I endeavored to apply those principles to my own writing. It’s a challenge which I try to tackle every day.

—Jackie Bischof

Look at the bones

Something’s wrong here but I don’t know what. This is what countless friends and colleagues have said to me about pieces they wrote, sometimes even pieces they edited. Almost every time, whatever is wrong with the piece can be cured by looking at its structure.

By structure I mean looking at the focus and purpose of each paragraph and section. Usually this can be done pretty quickly in an outline. In a magazine-style feature, for example, you might have a few paragraphs of introduction, followed by what journalists call a nut graph (a paragraph that sums up the main point of the piece and hints to the reader where we’ll be headed next), then perhaps a step-back to add context and background.

When looking at the structure of a piece, I ask myself:

- Do we have everything we need, with nothing extraneous?

- Is the information in the right order?

- If something could go two different places, where does it serve readers best? Where can it accentuate drama, tension, and contrast?

To make extra sure, sometimes I’ll print out a piece and cut up every paragraph so I can more easily move the order around. Don’t get duped by transition sentences at the beginning and end of paragraphs—it can be tempting to use those as a guide, but they are easily changed.

Of course, an editor doesn’t have to worry about a structural edit if the writer got the structure right in the first place. Outlining is the writer’s greatest asset here. Even if the information unspools in a slightly different way, you at least had a solid foundation from which to deviate.

—Alex Ossola

Find your voice by finding an ear

It sounds so simple to just “write how you talk,” but writing and speaking originate in different parts of the brain—which is why the most eloquent speaker you know might not be a great writer, and your cleverest Twitter follower might be tongue-tied IRL. As with any skill, finding your writing voice takes time and practice.

The bad news is even the clearest writing can make people’s eyes glaze over if it lacks a unique voice. The good news is—you already have one. In fact, you probably have several. It’s the language and tone you use when you speak to people, and chances are, you probably speak to different people in different ways. Here’s a method for connecting speaking tone with writing tone:

1️⃣ Identify a person who would be the perfect reader for the specific piece you’re working on. Let’s say it’s your witty friend Lottie. When you talk to her you feel both sharp and at ease.

2️⃣ Start writing the piece as if its only reader will be that person. Imagine it’s an email or a long series of texts, something that lives somewhere between chatting on the phone and a formal essay. Don’t think too hard about what you’re saying, just imagine saying it to Lottie.

3️⃣ Step away for a bit. Work on something else, get some sleep, and revisit the next day, if you can.

4️⃣ Spice it up (or spice it down). Read your piece aloud. Anywhere you find yourself stumbling, smooth it out until you stumble no more. Add more colorful language as it comes to you, and take out jokes that would slay with Lottie but might not make sense (or go down easily) with others.

—Susan Howson

Writing advice from our newsroom

On getting started:

“If you’re having trouble getting started, just put some words on a page. You can always come back and change them later.” —Alex Ossola, membership editor

“These days I start with ‘What are the facts?’ to stop myself from overthinking. I list them, and [the piece] flows from there.”—Alexander Onukwue, West Africa correspondent

On the process of writing:

“Economize your words. It might mean more time on your end but it means less time for the reader, and a sign of respect.”—Heather Landy, executive editor

“At some point I made the decision to stop thinking about how much better a story could have been (under different circumstances or in the hands of someone better!) and just make it as good as it could be (written by me, in the circumstances I was in). It helped a lot, and I think this approach might provide some sanity.” —Annalisa Merelli, senior reporter

“Ask yourself: ‘How can this be weirder?’ Allow yourself to stretch the borders of the topic and entertain seemingly zany tangents.” —Anne Quito, design reporter

On self-editing:

“Be ruthless and kill your darlings. It may be a wonderful sentence, but it also might need to go so that the rest of the piece can be more cohesive. It’s ok, you’ll write wonderful sentences once more!” —Susan Howson, email editor

“Read your piece out loud to catch clunky or unclear writing. If that feels awkward, imagine you’re hosting your own podcast.” —Lila MacLellan, senior reporter

“Stop using complicated phrases to make you sound clever.” —Hasit Shah, news editor

Have a great weekend,

—Alex Ossola, membership editor (even editors still need editors)

—Jackie Bischof, talent lab editor (still can’t with possessive case)

—Susan Howson, email editor (maybe wrote this specifically for you)

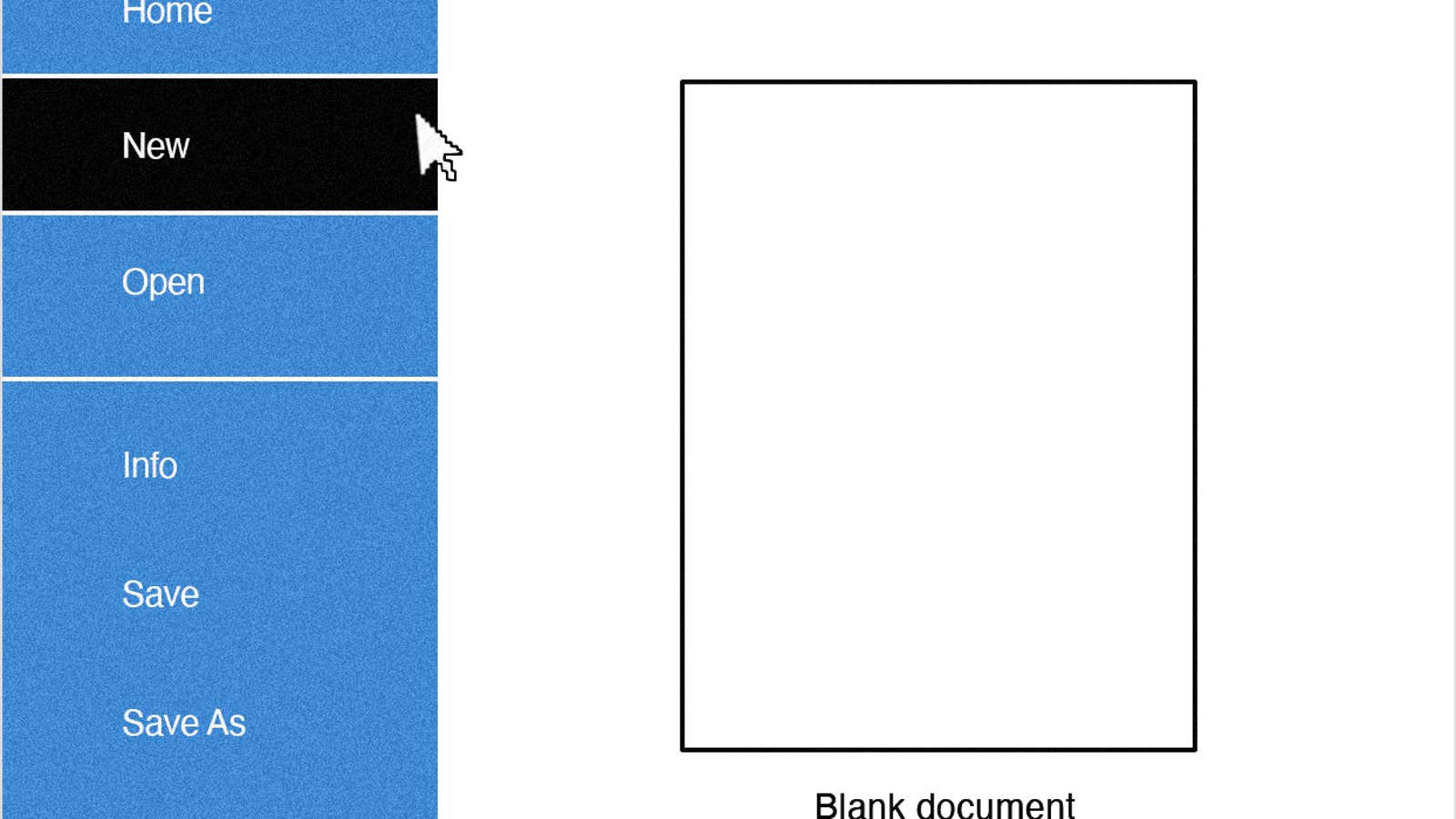

One ✍️ thing

A great way to get better at writing is to get into the practice of doing it. A daily habit of a few hundred words can go a long way towards developing your comfort with writing as well as your unique writer’s voice. If you need a little help making that habit, the website 750 Words can provide you with some structure.