For Quartz members—Four billionaires walk into a room

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

On Monday, Apple’s Tim Cook, Alphabet’s Sundar Pichai, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg are scheduled to appear—virtually, at least—before the US House Judiciary Antitrust Subcommittee. This is no Zoom happy hour: The four will take questions over accusations of antitrust abuses at their companies. Today we’ll talk about how they ended up there. But first, a recap:

Ant Group, the fintech spinoff of China’s Alibaba, announced plans to go public—an IPO that could make it bigger than Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo combined. Chinese bank losses are shaping up to be major, and the price of oil is working for OPEC at US producers’ expense. India’s richest CEO has a plan for 5G, coronavirus is boosting US used car sales, and Netflix wants a franchise. Also, we’re all buying stretchy clothes.

Our most recent presentation: How startup cities around the world are challenging Silicon Valley. Your most-read story: The chair that every remote worker wants hasn’t been invented. This week’s most relatable member: the reader of Does CBD actually work?

Okay, put your thimble on the board and organize your bills. We’re playing monopoly.

Message in a bottleneck

If you ask entrepreneurs about the power of the tech giants, you’ll likely be reminded that Google once seemingly had no chance of unseating Yahoo, or that some commentators worried about the MySpace monopoly. Incumbents often look insurmountable until suddenly they don’t, and that ethos is built into Silicon Valley’s self-conception. David beat Goliath with only a sling and a bit of startup hustle; just imagine what he’d have done with tens of millions from Andreessen Horowitz.

That brash optimism was on display back on Nov. 2, 2016, when Microsoft rolled out its Slack competitor, Teams. That same day, Slack took out a full-page ad in The New York Times, written as an open letter to Microsoft. “We’re genuinely excited to have some competition,” Slack declared, adding that “If you want customers to switch to your product, you’re going to have to match our commitment to their success and take the same amount of delight in their happiness.”

This week, Slack filed an antitrust complaint ($) against Microsoft with the EU’s competition authorities, acknowledging, in effect, that acquiring users isn’t only about delighting in their happiness. Slack has accused Microsoft of abusing its market power by bundling Teams with its Office suite, an echo of the US government’s suit against Microsoft in the 1990s over its bundling of Internet Explorer with the Windows operating system. (Analyst Ben Thompson has a good discussion of Microsoft’s strategy, published before Slack’s antitrust complaint was public.)

A spokesperson at Slack said that the company “simply wants fair competition and a level playing field.” Simple or not, it’s an evolution for Silicon Valley—from the assumption that any company more than 10 years old is ripe for disruption to a recognition that disruption depends on policymakers committed to fair competition.

When the CEOs of Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, and Facebook face Congress next week for a hearing on antitrust, they’ll have to answer complaints from consumer groups, activists, economists, unions, Main Street businesses, and more. Those combined grievances have been dubbed the “techlash,” and extend far beyond issues of antitrust. But that phrasing obscures the fact that on antitrust issues the big platform companies are increasingly facing scrutiny from aggrieved tech companies, too. —Walter Frick, membership editor

Why is it called antitrust?

A “trust” is a group of firms or industries organized to concentrate power, and reduce or eliminate competition. The model developed in the 1880s, as burgeoning oil baron John D. Rockefeller sought to consolidate his holdings across state borders. As policy analyst Matt Stoller explains in his book, Goliath:

In 1882, an oil refiner named John D. Rockefeller helped invent a centralizing legal tool to capture industries across state borders. He placed all stock from various oil properties into one legal structure called a “trust.” Known as the Standard Oil Trust, Rockefeller’s oil companies might look independent legally, but the trust’s board of directors set policy for the combined group. With this new legal tool, Rockefeller built the largest and most powerful monopoly of the era.

Standard Oil is often referred to as the first trust, and marked the birth of the giant corporations that now dominate the daily lives of people around the world. While Standard Oil consolidated the oil industry, financier John Pierpont Morgan organized General Electric and US Steel, and captured the railroads. Rich Uncle Pennybags, the round-faced, mustachioed mascot created in 1936 for the Monopoly board game, was modeled on Morgan.

The cost of consolidation

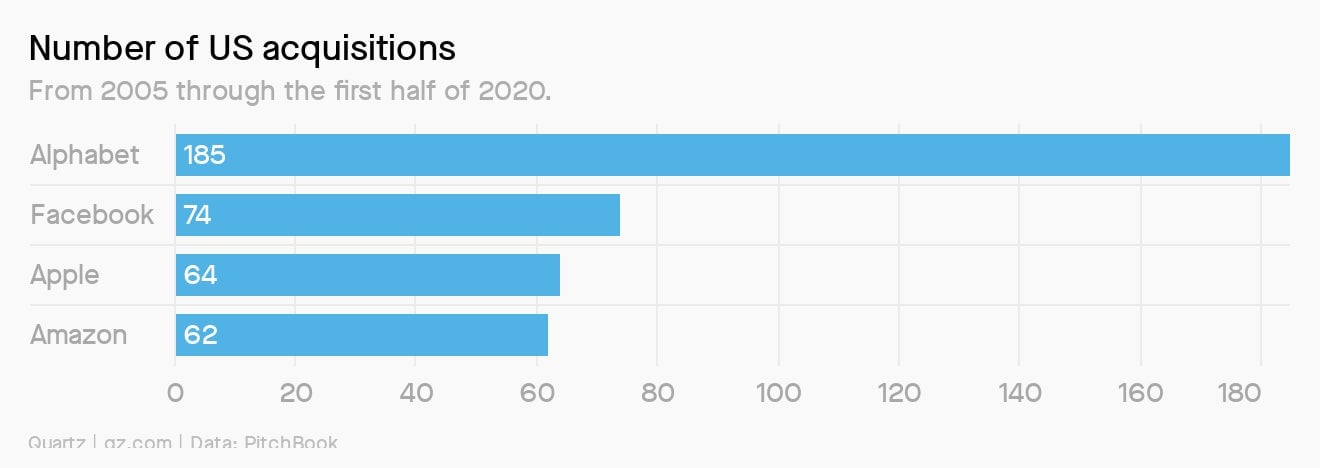

Since 2005, Alphabet, Apple, Amazon, and Facebook have acquired 385 other US companies, according to PitchBook. Those acquisitions have channeled $86 billion into the pockets of entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, early employees, and other startup investors.

Billion-dollar buyouts motivate more tech founders to get started, but they can also deter entrepreneurship. Albert Wenger, a managing partner at Union Square Ventures, has warned that the big tech companies have a “kill zone” around them, meaning startups that operate too closely to their businesses have no chance of success.

In a 2019 working paper that explored the kill zone (pdf), economists at the University of Chicago examined nine acquisitions by Google and Facebook worth $500 million-plus. They found that over the three years following the acquisitions, VC investment in startups competing with the acquired companies fell by 46%.

European-style

Not all tech giants are the same. Next week, Facebook will be questioned over its WhatsApp and Instagram acquisitions, Google its digital-advertising dominance and favoritism in search results, Amazon its undercutting of third-party sellers, and Apple its closed app platform. That’s a lot of ground to cover, and if Zuckerberg’s 2018 Congressional appearance is any indication, the questions are unlikely to be as aggressive (or nuanced) as the systems they’re about.

Things are a little different in Europe, where GDPR is just one example of a more robust regulatory landscape for tech. Leading the European Union’s regulatory fight is Margrethe Vestager, who in September won a second five-year term as the EU’s competition commissioner. Vestager has levied billions of euros in fines against Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and other Silicon Valley stalwarts for breaking the bloc’s antitrust rules.

“They’re not startups any more, fighting for a toehold among big, powerful companies,” she said during a conference in 2018.” Now they themselves are the big beasts. And if they deny today’s startups a chance to do what they did, and carve out a market by doing things differently, then we all lose out on the benefits of innovation.”

Getting on the board

Monopoly isn’t just a tech CEO’s game—many niche industries face increasing market concentration. In his newsletter, BIG, Stollar identified a few that might surprise you:

🚽 Portable toilets

📞 Prison phone services

👄 Dentistry

👊 Mixed martial arts

✉️ Mail sorting software

🐎 Horse shows

🐶 Veterinary clinics

One definitely-not-monopoly (a Parcheesi?) is the cannabis industry. In the 2019 fiscal year, US attorney general William Barr ordered investigations of 10 cannabis mergers, equal to 29% of the antitrust division’s investigations during that period. Critics of those investigations—including a Department of Justice whistleblower—say his concerns were wildly overblown.

“These mergers involve companies with low market shares in a fragmented industry; they do not meet established criteria for antitrust investigations,” whistleblower John Elias testified last month. “The rationale for doing so centered not on an antitrust analysis, but because [Barr] did not like the nature of their underlying business.”

Essential reading

Want to keep going down this rabbit hole? Here’s some recommended reading:

- Our field guide on taming big tech

- Nobel-winning economist Jean Tirole on how to regulate tech monopolies

- A precedent for Amazon competing with so many companies

- A guide to modern antitrust in plain English from economist Fiona M. Scott Morton

- A series of reports on solving the problems caused by tech platforms

And if you’re in the recommending mood, why not refer a friend to Quartz membership? With this link and the code Memberreferral, they can enjoy 40% off the first year.

As always, we want to hear from you: feedback, questions, ideas, or your favorite Monopoly piece (no wheelbarrows).

Thanks for reading! And best wishes for an expansive end to your week,

Walter Frick

Kira Bindrim