For Quartz members—Can Boeing recover?

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

One pandemic and nearly one million deaths later, no regular person has been giving much thought to Boeing’s 737 Max aircraft, which dominated headlines for months last year after it crashed twice and killed nearly 350 people.

Last week though, a nearly 240-page Congressional report (pdf) offered the most comprehensive look yet at one of the worst US public safety failures—one that many have come to see as a painful illustration of the flaws of America’s model of capitalism. Today we’re looking at Boeing, and what went wrong with the 737 Max.

But first, a recap: The UN kicked off the mother of all Zoom meetings, Tesla held a socially distanced battery confab, and Uber is getting into office carpools. Oracle and Walmart miiiiight have a deal to save TikTok, if only everyone could agree on what it is. China imprisoned a property tycoon who criticized Xi Jinping, and Americans are running out of houses to buy. Also, things aren’t looking great for Quibi.

Your most-read story this week: How South Africa’s “Jerusalema” became a global dance favorite. And most relatable member goes to whoever was reading Resilience is the new happiness. Hang in there.

Okay, let’s get started.

The Boeing tragedy wasn’t about software

It’s not normal for a brand-new airliner to fall out of the sky. But that’s what happened on Oct. 28, 2018, when a Lion Air flight using the 737 Max plane plunged into the sea less than 15 minutes after taking off from Jakarta, killing 189 people.

Tracing the trail of errors that doomed those passengers leads back to 2010, when the other member of commercial aviation’s “duopoly,” Europe’s Airbus, unveiled the fuel-efficient A320neo narrow-body jetliner. Boeing was at the time leaning toward replacing its 50-year-old 737 program with a new aircraft, which would have taken about a decade and $10 billion to develop (pdf, p. 37). But after a stern warning from an airline to present a rival option or lose business, the company went into panic mode.

Revamping the 737 to compete with the A320neo involved adding more powerful engines that were placed further forward on the aircraft, changing its aerodynamics. To adjust for that, a new software control was added: the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System. It was designed to pitch the nose of the plane sharply down in response to flight angle data that indicated a potential stall—and to do so repeatedly.

Boeing was authorized by the FAA to carry out large parts of the safety certification itself, and overrode concerns raised internally about the chances the new system could cause a fatal crash. To avoid having the plane certified as a new model, the company didn’t publicize the presence of MCAS, which allowed Boeing to keep a commitment to its launch customer, Southwest Airlines, that expensive flight-simulator training wouldn’t be required. That also meant not telling the pilots about MCAS, or putting it in their operation manuals. The FAA, unwilling to compromise Boeing’s bottom line, went along with the recommendations.

By the time the plane went into service, MCAS had been made about four times more powerful, and could trigger repeatedly based on data from a lone sensor—even if that data was wrong.

After the first crash, the FAA didn’t ground the Max, though an internal risk assessment pointed to the chance of another deadly crash. Then in March 2019 another 737 Max went down, an Ethiopian Air flight carrying 157 people, even though the pilots were prepared for MCAS this time. First China, then the world, grounded the plane.

Boeing’s dysfunction can be traced even further back than 2010, to a 1997 merger with McDonnell Douglas that heralded “a move away from expensive, ground-breaking engineering” to one “devoted to keeping costs down” and shareholders happy. Over the period of the Max’s development, the congressional report noted, Boeing spent $60 billion on dividends and buybacks while spending around $3 billion (pdf, p. 37) to create the Max. As Big newsletter writer Matt Stoller put it, the joke was “McDonnell Douglas bought Boeing with Boeing’s money.”

Add the pandemic to the mix, and it’s difficult to believe that either the FAA or Boeing are equipped to do a better job than they did the first time around. The government’s track record on dealing with a catastrophic crisis doesn’t look any better in late 2020, and Boeing has laid off thousands of workers as orders drop away.

By the digits

4 seconds: The amount of time Boeing gave 737 Max pilots to sift through multiple associated alerts and counteract an erroneous MCAS activation.

15: The additional fatal flights the FAA forecast could occur over the lifespan of the 737 Max if MCAS were not fixed (pdf, p. 29).

18 months: How long it’s been since a 737 Max took to the skies.

355: Number of Max orders canceled in the first half of 2020.

~56%: Decline in Boeing’s share price this year.

$2.4 billion: Boeing’s second-quarter loss, which includes more than $2 billion in severance costs for 19,000 employees laid off as the pandemic decimated air travel.

$2.9 billion: Boeing’s second-quarter loss in 2019, when it posted a $5 billion charge related to the 737 Max program.

$1,033,680: The estimated cost of fixes, mainly software updates, to make the 73 Max planes in the US fleet safer (pdf, p. 20).

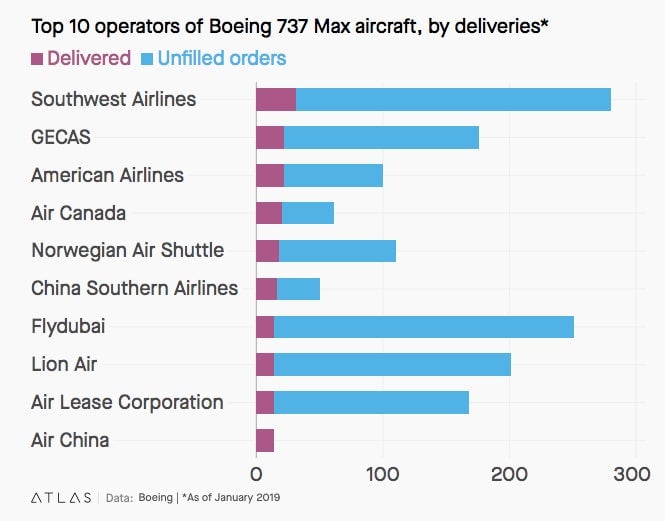

31: The number of 737 Max jets in Southwest Airlines’ fleet as of January 2019, when the plane was grounded. At the time, Southwest was waiting on orders of a further 249 of the aircraft.

Let’s get technical

In August 2020, the FAA proposed a number of fixes (pdf) to address some of the worst design flaws of MCAS. The comment period on the proposal closed on Monday (Sept. 21), with about 220 submissions posted online.

But the FAA is still working within the lines drawn by Boeing, many commenters point out. And it’s only solving for problems that already happened—not the worst-case scenarios that could occur if the software misbehaves in ways we haven’t seen yet. As Quartz noted last year, a fatal flaw in the whole process was making conveniently sunny assumptions:

The idea that the anti-stall system could work fine on a single sensor, that a malfunction wouldn’t be catastrophic, or that pilots would act a certain way in an emergency, were all based on assumptions that, now, turn out to have been wrong. Boeing might have been able to avoid this by assuming the worst: The sensor will fail, MCAS will activate erroneously, pilots won’t immediately know what to do.

One comment submission from the British Airline Pilots Association is well worth reading for how it probes the thinking underlying the FAA’s latest safety proposals. Okay, so you disable this troublesome software if the sensors disagree by X amount. Well, what if they disagree by slightly less than X, and MCAS is triggered: What are the chances of that and how catastrophic might that be?

Even within the FAA there’s dissatisfaction with the proposed fixes.

Some pilots and engineers believe that a really robust safety process would require Boeing to rip off the “band-aid” of MCAS entirely, considering it’s a software fix to what is fundamentally an aerodynamics problem. Many say Boeing has pushed the 737 model as far as it can, and needs to go back to the drawing board. Doing that might also be what’s required for Boeing to truly win back the public’s trust.

Will the Max really come back?

It would be unprecedented for Boeing to retire a new plane that it expects to generate billions of dollars in revenue. The cost to the economy, and Boeing’s scores of suppliers, would be even more painful than the production halt that’s been in place since January. But with the 737 Max crisis—as with the pandemic—we’re in unprecedented territory already.

In a tiny glimmer of hope, last month Boeing got its first new orders for the Max since its grounding, from Polish charter flight operator Enter Air. (For the year, cancellations have put Boeing at negative new orders.)

Boeing—and any airline hoping to use the plane—is fighting an uphill battle. Even before the pandemic, many passengers said they would never fly the Max again. Since then air travel has plummeted, and isn’t expected to recover to pre-pandemic levels until 2024. Many of those who do travel are going to be deeply nervous because of Covid-19, at least until a vaccine is widely available. Will airlines successfully woo those passengers with a flight on an aircraft that’s been involved in two fatal crashes?

Keep reading

- Flawed analysis, failed oversight: How Boeing and the FAA certified the suspect 737 MAX flight control system

- The four-second catastrophe: How Boeing doomed the 737 Max

- Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg’s letter on 737 Max safety

- The 1997 merger that paved the way for the Boeing 737 Max crisis

- The non-bailout: How the Fed saved Boeing without spending a dime

- Our field guide to Boeing’s 737 Max crisis

- Final report of the House Committee on Transportation & Infrastructure (pdf)

- Public comments on the FAA’s August 2020 safety proposal for the 737 Max

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a safe end to your week,