For Quartz members—Palantir goes public

Depending on who you ask, Palantir is either the architect of an immoral panopticon, or a smoke-and-mirrors operation passing off routine human labor as technical wizardry. Or, more mundanely, maybe it’s just Tableau for spies.

Depending on who you ask, Palantir is either the architect of an immoral panopticon, or a smoke-and-mirrors operation passing off routine human labor as technical wizardry. Or, more mundanely, maybe it’s just Tableau for spies.

The secretive unicorn became a publicly-traded company this week, going out of its way to distinguish its philosophy from its Silicon Valley brethren. But before getting into all things Palantir, a recap: The Apprentice seems to have saved Trump from financial ruin, Wall Street is betting the US presidential election will be resolved by Inauguration Day, Coinbase has a controversial new approach to social activism, one-in-four women in the US and Canada is considering a career step-back because of Covid-19, and maybe sex doesn’t sell after all.

Your most-read story of the week is on the countries with the biggest immigration gains and losses during Trump’s first term. Most-relatable member goes to whoever’s reading All the ways bad sleep is hurting you. (Don’t be afraid to go take a nap!)

Finally: Don’t miss our new presentation on 10 ways Covid-19 has changed the global economy, Quartz Africa invites you to a virtual event on Oct. 8 all about China’s influence on the continent, and you can now share paywalled articles with your friends on qz.com.

Now, time to get philosophical about Palantir.

Palantir, the ideology company

What is a company for? Ostensibly, to make products for customers and profits for investors. The digital economy is different. Google makes products out of its customers. For most of its existence, Amazon has not been profitable. And then there is the imperative to change the world.

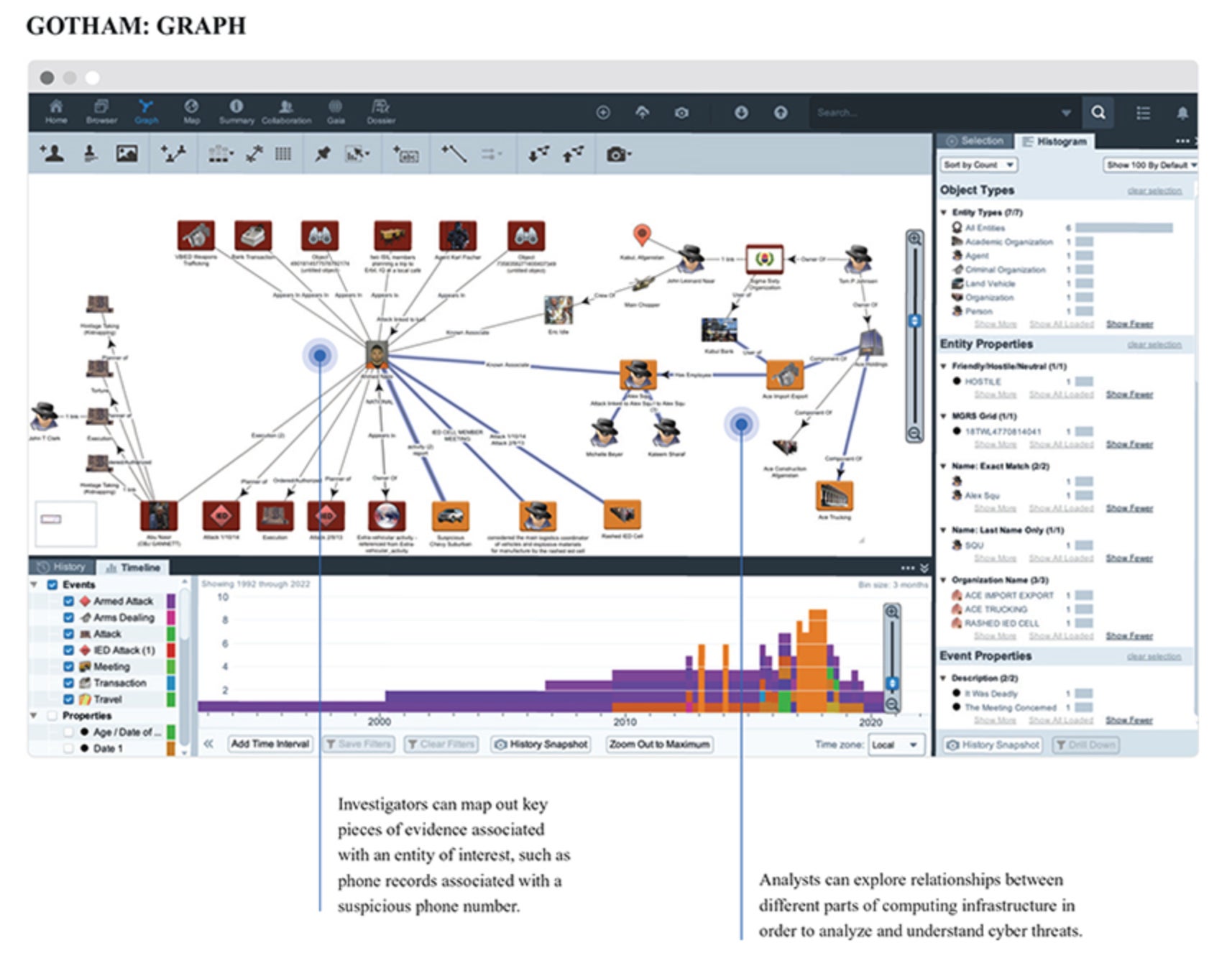

Palantir is not merely a purveyor of data management software, initially to military and intelligence agencies and now global corporations, capable of funneling disparate data sets into user-friendly interfaces and visualizations said to help with everything from military strikes to building jets.

Judging by the letter accompanying its prospectus, authored by CEO Alex Karp, it is also an ideological project. To dispel fears about a company that can inspire images of Minority Report, he decries the abuse of personal data by many giants of the digital economy, and answers our first question: Companies ought to act in the public interest; after all, “the privilege to engage in private enterprise…is a product of the state and would not exist without it.”

Public interest takes different forms. Some engineers at digital firms like Google, Facebook, and even Palantir itself have seen it as their duty to publicly protest how government agencies use their products to enable the killing of civilians in military strikes, the spread of election disinformation, and the abuse of illegal immigrants. Some companies backed off; Palantir took a different approach.

“Our society has effectively outsourced the building of software that makes our world possible to a small group of engineers in an isolated corner of the country,” Karp, who recently moved Palantir’s corporate headquarters from Palo Alto to Denver, Colorado, writes. “The question is whether we also want to outsource the adjudication of some of the most consequential moral and philosophical questions of our time. The engineering elite of Silicon Valley may know more than most about building software. But they do not know more about how society should be organized or what justice requires.”

Set aside that Palantir co-founder Peter Thiel has dedicated his career to reorganizing society, from seasteading and ending college to promoting monopolies and president Donald Trump. What Palantir offers is not so much a nuanced theory of justice as a singular focus on product-market fit: The government wants the best technology, at a time when many of the best technologists are having second thoughts about how their tools are used. Palantir, like a traditional defense contractor, won’t waste time worrying about what justice requires.

Striking a blow in the culture war is more than a lubricant for the company’s business model; it may have helped its stock price as rampant retail stock trading draws buyers to businesses with powerful, if not often accurate, stories to tell.

I’m contractually obligated to mention here that Palantir’s name is a reference to magical stones in the novels of JRR Tolkien, which allow users to peer through time and across realms. Less often mentioned is that when Tolkien’s characters use the Palantir stones, they are typically deceived by what they see (pdf).

The business problem

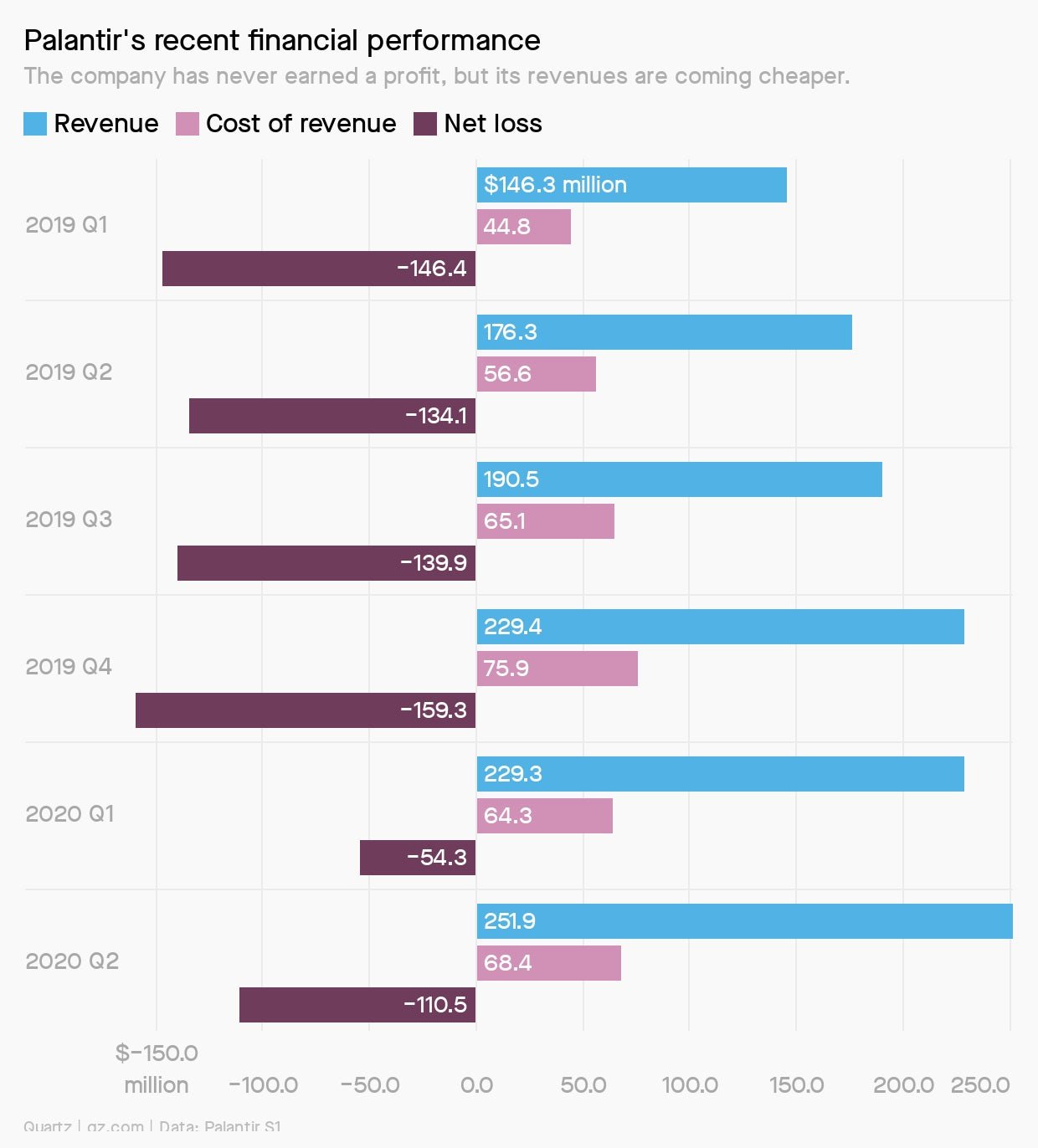

Ideology aside, Palantir’s financial prospects are hardly golden. Before the listing, valuations were expected in the $20 to $40 billion range; about half way through the second day of trading, investors valued the firm at $21 billion. That’s about 20 times the company’s forecast 2020 revenue.

Palantir wants to be valued like a “software as a service” (SaaS) company—the darlings of investors, these firms build a software product which can then be used by a functionally infinite set of users. Think Zoom’s video-conferencing software, or Microsoft’s Office apps: it takes money up front to build the software, but much, much less to acquire new users. Palantir’s two data management platforms, Gotham and Foundry, are marketed this way.

The issue, however, is that both platforms appear to require significant customization and engineering support for users. Palantir brags that its engineers are on the front lines in places like Afghanistan alongside its users, which sounds badass, and is also very expensive to scale. The company’s prospectus says it is not throwing people at problems, and it predicts that the costs of its services will continue to fall, particularly as revenue from on-going customers continues to grow.

Palantir has spent $1.5 billion on its platform thus far, engineering that may set it apart from potential competitors. However, in attempting to win market share in industries ranging from finance to aerospace engineering (current customers include Credit Suisse and Airbus), it may find itself competing with internal solutions developed and marketed by specialists. SpaceX developed a novel systems engineering and integration platform to build its rockets, while asset management giant Blackrock built Aladdin, an investment management platform now used by Apple, Microsoft, and Alphabet.

Consider the numbers: Public SaaS companies have traded at valuations averaging 16 times their previous twelve months of revenue—but these firms are generally growing fast, with revenue increasing at 50% or more year over year, and are profitable. Palantir has averaged 20% annual growth over the last five years and never been in the black.

Sometimes love is having to sue your customers

Palantir is part of a relatively young class of venture-backed companies seeking to make a business out of working for the US government, alongside SpaceX and Anduril, a national-security company founded in part by former Palantir employees, if you couldn’t guess from yet another Tolkien allusion.

These companies share something in common, according to Katherine Boyle, a partner at the venture fund General Catalyst, and Anduril board member. Traditional government contracts state both the problem and the requirements for the solution, which newer firms with Silicon Valley mindsets often see as inhibiting innovation. But trying to convince the government to change how it writes contracts often leads to conflict, as traditional contractors with significant political influence fight to preserve traditional methods.

Palantir and SpaceX have both fought for contracts that emphasize commercial buying, with fixed prices and limited requirement-setting. It has been contentious: SpaceX sued the US Air Force in 2014 to compete for rocket contracts, eventually winning billions in launch business.

In 2016, Palantir sued the US Army over a contract to provide “battle management software.” Palantir won the right to compete, a victory the company’s prospectus suggests will significantly increase the amount of government contracts it can win.

The CIA plays venture capitalist

One of the first outside investors in Palantir, back in 2006, was a little shop called In-Q-Tel. It’s not your typical fund: It’s non-profit, and it was founded by the CIA. (And yes, the Q is for James Bond’s Q.)

The US intelligence agency, once responsible for creating spy satellites and supersonic planes, felt it was losing its high-tech touch in the nineties as information technology became dominated by the private sector. Venture capital was where the tech was, and the CIA decided to go there, launching a fund led at first by former Lockheed Martin CEO Norman Augustine.

At the beginning of 2018, the most recent year it has publicly reported data, In-Q-Tel reported about $450 million in investments; the fund appears to aim mainly at seed and early-stage investment rounds in companies that manage big data, launch satellite sensors, develop nanotechnology, and organize geospatial imagery.

“We have a board observer position, and we are able to influence where it goes with its product,” an early In-Q-Tel leader said. “There is the aspect that at the end of the day, we want the technology, obviously. That’s sort of our, for a lack of a better term, our special sauce, if you will, of getting in there with that venture relationship.”

For young companies daunted by federal procurement rules, the CIA venture fund was a key way to develop the understanding needed to compete for government contracts. The imprimatur of the spy agency also gives these firms a sexy gloss that helps them raise new money from traditional private investors.

Palantir, explicitly founded to work with US intelligence agencies, was an obvious candidate for In-Q-Tel’s investment. It’s fascinating, then, that Palantir’s relationship with US spy agencies appears to have soured in recent years: It’s not clear either the CIA or the National Security Agency is using the company’s platforms.

A lesson in marketing

Palantir’s greatest success—and the one most reflective of the Silicon Valley ethos the company may or may not be abandoning—was in how it got the military to buy its platform.

As the lawsuit story above highlights, going through the front door wasn’t exactly an easy option. But successful startups find a way in, and one move was providing free training and software to soldiers. Palantir’s Gotham platform was used in Afghanistan by soldiers combining maps, intelligence reports, and records of roadside bombings to plan their missions.

This helped win over the rank and file, who appreciated the more intuitive tools and support offered by Palantir’s engineers. It’s not unlike how instant messaging platform Slack spread initially, winning over individual teams rather than corporate IT departments. Senior Army officials were perturbed because the freebies likely violated government contract rules—but they wound up putting Palantir on a small contract to solve the problem, effectively paying for the company’s marketing.

The act-first, ask-questions-later approach offers shades of Uber selling rides without regulatory approval in cities, then using its customer base as leverage to win the right to operate. For Palantir, getting troops in the field to use its platform paid off when Army officials saw that their troops were more comfortable with it, compared to a kludgier product delivered by traditional military contractors.

“I walked away convinced that Palantir is much easier to use,” Heidi Shyu, the Pentagon official in charge of buying gear for the military between 2011 and 2016, told New York Magazine.

Keep reading

- Read Palantir’s prospectus and CEO Alex Karp’s letter for yourself.

- Palantir went public in a unique way—as a “direct listing,” which can simplify the complex IPO process. Was it an improvement?

- Further exploration of Karp’s philosophy is found in this essay by Moira Weigel, who read Karp’s German-language PhD thesis to understand his views of aggression in the life-world.

- NYU Marketing professor Scott Galloway reads Palantir’s S1: “The firm spent $911 million in marketing over the last 24 months, roughly half of what Tide detergent spent over the same period.”

- A profile of the company by Sharon Weinberger has lots of inside scoop from the Pentagon on Palantir.

- Alex Clayton, a partner at Meritech Investments, keeps track of public SaaS companies.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a safe end to your week,