For members—McKinsey’s moment of reckoning

Hi Quartz member,

Hi Quartz member,

Consulting firms aren’t supposed to be in the news. They work behind the scenes, trying to help companies make better decisions. But McKinsey & Co., the oldest and most influential consultancy, has been in the headlines a lot lately, attracting attention for its unsavory clients and questionable practices. In a rare acknowledgement of its missteps, last month the company even agreed to pay nearly $600 million for its role in the opioid crisis.

But first, a recap: Stripe’s valuation hit $95 billion, Europe is anxious about the AstraZeneca vaccine, and China is boosting vaccine diplomacy with visa perks for foreigners. America? Running short on wood. The IKEA catalog? Now an audiobook. This article? We put it on sale as an NFT.

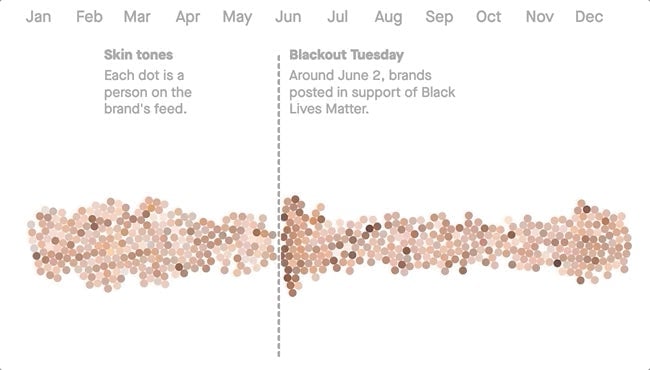

Your most-read story this week: An analysis of 27,000 Instagram images show that fashion’s BLM reckoning was mostly bluster. And don’t forget the member-exclusive part: All the data behind which brands are keeping their promises.

Okay, now don your best suit. We’re talking about McKinsey.

Consulting on its image

For nearly a century, McKinsey has been the gold standard in management consulting, the nebulous and occasionally controversial billion-dollar industry based on giving advice.

Since its founding in 1926 by James O. McKinsey, the firm has advised the Eisenhower White House, the Vatican, NASA, and 22 of China’s largest state-owned enterprises. The company had a role in inventing the UPC code on packaged goods and in defining modern corporate hiring.

In recent years, however, McKinsey’s shine has begun to tarnish. The company has been embroiled in numerous scandals, from its choice of clients—among them Purdue Pharma and the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency—to its secretive internal hedge fund rife with conflicts of interest. It’s been implicated in abetting corruption in South Africa and Mongolia, accused of enabling oppression in Saudi Arabia, and suffered the embarrassment of a partner’s arrest as part of a massive insider trading scandal.

Stung by the criticism, McKinsey has begun to make amends. In December, the company issued a quasi-apology for its role in the opioid crisis, which had included recommending how Purdue could boost sales of OxyContin even as public concerns about the addictive drug grew. On Feb. 4, the company agreed to pay $573 million as part of a settlement with US state attorneys general.

The firm’s senior partners also voted out managing partner Kevin Sneader last month after just one term, a rarity at McKinsey, and elected Bob Sternfels to replace him. That follows the 2019 adoption of a new client selection process that, among other things, prevents McKinsey from working for “defense, intelligence, justice, or police institutions in non-democratic countries.”

For an organization that prides itself on its loyalty, dedication, and principled business practices—in an internal report, McKinsey compared itself to the Jesuits and the US Marine Corps—the waves of scandal are a humiliation. Whether it can recover its halo remains to be seen.

By the digits

30,000: McKinsey global employees

130: Cities with McKinsey offices

0: McKinsey headquarters (pdf) (The company claims to have no HQ; its managing partner chooses which office to work out of.)

34,000: McKinsey global alumni

$67,500: Weekly rate in 2020 for one junior McKinsey business analyst (pre-pandemic discount)

$255,000: Weekly rate for a team of five McKinsey consultants (pre-pandemic)

43: University of Chicago MBA students hired by McKinsey in 2020, the most of any employer

$165,000: Median annual base salary for Chicago MBAs hired by management consulting firms

McKinsey’s business model

Companies hire consulting firms like McKinsey or its competitors—its two biggest are Bain and Boston Consulting Group—because they lack the expertise, resources, or independence to solve a business problem on their own. But they also hire McKinsey to say they’ve hired McKinsey.

Having McKinsey vouch for a decision sends a signal to the board and investors that management has done its due diligence, and that the best consultants money can buy have signed off on the move, whether it’s a merger or new product launch.

It’s hard for a client to assess whether McKinsey will do a good job before they’re hired, since they’re being tasked with something the company can’t, or won’t, do itself. Even after all is said and done, it’s hard to know how the firm performed, since there’s nothing to compare it with. So instead of relying on objective measures, companies trust McKinsey because it projects trustworthiness. Price is also a factor: The more McKinsey charges, the more reputable it seems.

McKinsey is famously selective in its hiring: The company gets about 200,000 applicants annually for just 2,000 spots. And once on board, its consultants still can’t relax. Like most consulting firms, McKinsey practices “up-or-out” management, meaning consultants who aren’t promoted are asked to leave. The system ensures a steady flow of new, and cheaper, talent, but also means McKinsey sends thousands of its alumni out into the world, where they become decision makers at their new companies and hire their former firm to consult. It’s a perpetual business-generating machine.

Can you McKinsey?

McKinsey’s rigorous hiring process includes tests with elaborate scenarios meant to duplicate consulting assignments. There’s a full practice test online (pdf) for the truly brave souls; for the fainter of heart, here’s a sample question:

Way Forward is a nonprofit organization that consists of more than 50 local offices in the UK. Way Forward Greater London (WFGLA) is one of these local offices. Typically the local offices work together with private and social sector organizations to pool efforts in fundraising campaigns, which typically address pressing community issues.

Currently, there is an economic downturn in the UK. This presents a challenge for WFGLA, because donations are decreasing when community need is high. The president of WFGLA has reached out to McKinsey to ask for support: “I need your help on improving our campaign effectiveness, which we define as the number of pounds donated per pound spent on the campaign. We really need to focus on increasing donations in these times!”

Which of the following pieces of information would be LEAST helpful in better understanding the current WFGLA situation?

Total amount of donations, in British pounds, collected by other WF offices across the UK.

Comparison of donations made to WFGLA by one-time donors versus regular donors over the past 5 years.

Market research on the public awareness generated by WFGLA campaigns over the past 5 years.

Comparison of campaign effectiveness with other local WF offices

We won’t leave you hanging; the answer is at the end of the email.

That McKinsey culture

Marvin Bower, the managing partner responsible for McKinsey’s rise in the 1950s and 60s, had strong ideas about how a McKinsey partner should and should not, dress. Suits were required. Facial hair and bow ties were frowned upon. Socks should be worn high so a client never witnesses the bare flesh of a consultant’s leg.

The dress code wasn’t just about Bower’s preferences. “If you have revolutionary ideas, they are much more likely to be listened to if you do not have revolutionary dress,” Bower told his biographer. “If you were an airline passenger, and the pilot came aboard the plane and he wore shorts and a flaming scarf, would you have the same confidence as you did when he came on with his four stripes on the shoulder?”

Today McKinsey has loosened up. It boasts of its diversity efforts, has significant philanthropic activities, including its own foundation, and claims to have zero net carbon emissions since 2018. Some things haven’t changed, though. On an online forum for aspiring McKinsey employees, new hires are advised to buy 15-30 dress shirts and three to six suits. And, it goes without saying, plenty of long socks.

Prominent McKinsey alumni

🏦 Lael Brainard, member Federal Reserve board of governors

🚃 Pete Buttigieg, US Secretary of Transportation

🇺🇸 Tom Cotton, US senator, Arkansas

💰 Jane Fraser, CEO, Citi

💻 Lou Gerstner, former CEO, IBM

🇬🇷 Kyriakos Mitsotakis, prime minister of Greece

🔗 Sundar Pichai, CEO, Alphabet

🌐 Susan Rice, former US ambassador to the United Nations

👤 Sheryl Sandberg, COO, Facebook

⛽ Jeff Skilling, former CEO, Enron

Keep learning

- The Witch Doctors: Making Sense of the Management Gurus, by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge

- The Firm: The story of McKinsey and its Secret Influence on American Business, by Duff McDonald

- Consulting on the cusp of Disruption (Harvard Business Review)

- Who says talent development has to stop when an employee moves on? (Quartz)

- McKinsey’s partners suffer from collective self delusion (The Economist)

Wondering about that sample question? The answer is 1: “The total amount of donations collected by other WF offices would be least helpful in and of itself, as different offices will target different population sizes and demographics and direct comparisons would be meaningless. B would help determine which types of donors to focus on. C and D would help determine the effectiveness of current campaigns.”

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for an advisable end to your week,