For members—The company capitalism couldn’t survive without

Hi Quartz member,

Hi Quartz member,

Here’s an exercise: Try adding up the minutes in your day when you’re not using a microchip. Your smart clock-radio has several; so do your microwave, smart TV, and Alexa. Needless to say, your phone and laptop are stuffed with them. The semiconductor chip is the fundamental unit of modern life, and it wouldn’t exist as we know it without ASML—a little-known Dutch company that makes the machines that make the microchips.

But first, a recap: India’s vaccine program has glaring data and communication issues, Apple’s privacy update shows the massive power of small design changes, and Basecamp put out a culture memo that’s quite controversial. Joe Biden’s families plan would revolutionize American life, and the Sony PlayStation had a record year, PS5 shortage be damned. Why has South Africa’s vaccine rollout been so slow? Is business journalism a good career choice? Is Zoom’s Immersive View the stuff of nightmares? Asked and answered.

Your most-read story this week: Ray Dalio says his new personality test is better than interviews. And most relatable member goes to everyone reading The $4,400 Hong Guang Mini EV is outselling Tesla in China. Yes, the $4,400 EV is cute.

Okay, now bust out the chips—no, not the Doritos. We’re talking about ASML’s grip on the semiconductor space.

Chips ahoy!

The world is running short of semiconductor chips—so short that Subaru temporarily closed a plant in Japan, 5G network rollouts are delayed, Apple is worried about production hiccups, and new PlayStation 5s are nearly impossible to find. The reason for the shortfall may be plain to see—pandemic production slowdowns, compounded by booming demand for consumer technology—but the shortfall itself shows the stunning ubiquity of the chip today, and the dense complexity of the supply chains that produce it.

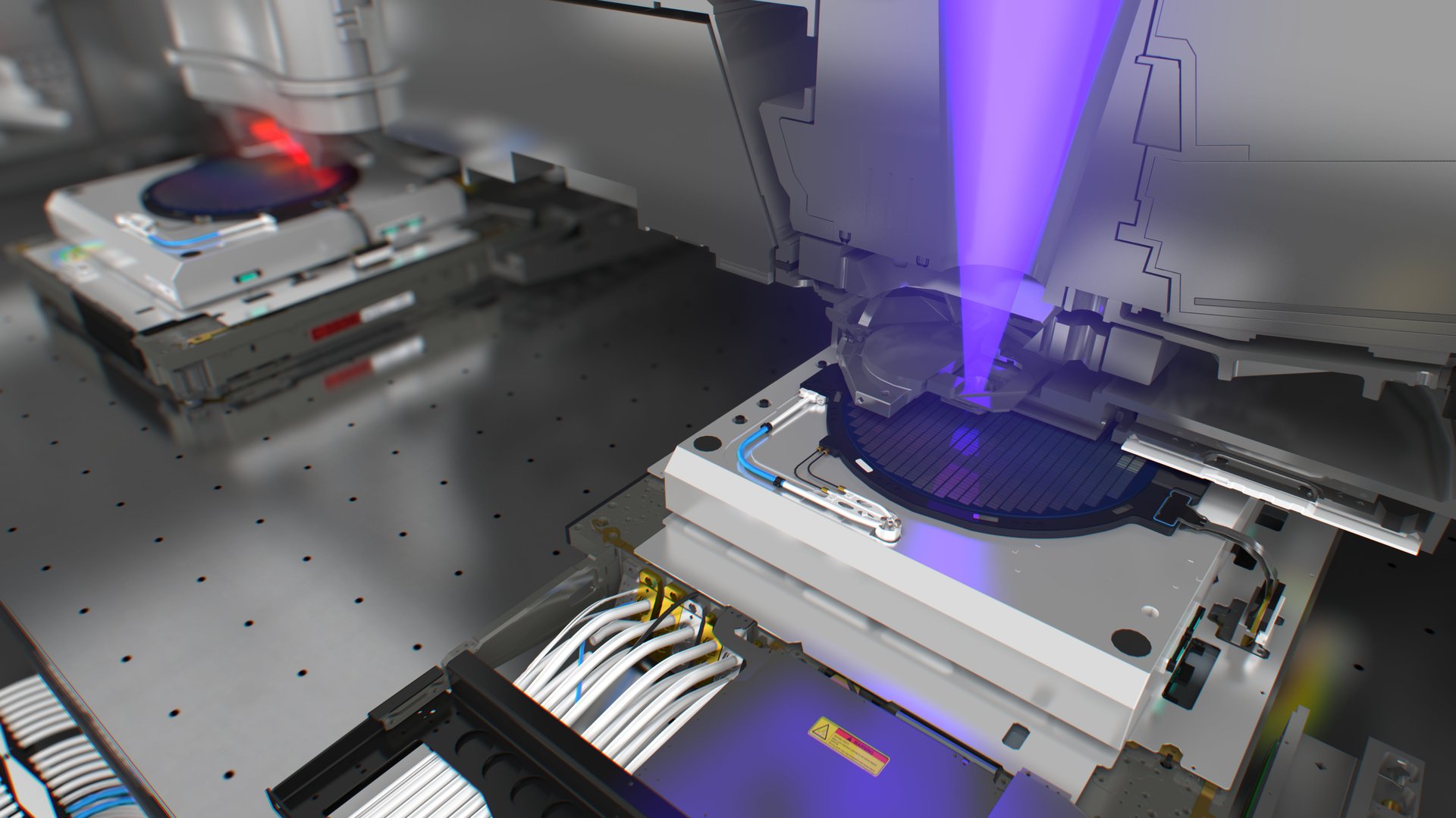

Which makes it all the more remarkable that a single Dutch company sits at the very heart of this $439 billion industry. At its headquarters in Veldhoven, in the Netherlands, ASML assembles photolithography machines, which etch circuit patterns onto chip wafers using low-wavelength light. Other companies make such machines too, but ASML controls more than 60% of the market. It is also the only manufacturer of the latest, most precise generation of chip-making machines, which use extreme ultraviolet light (EUV), with a wavelength of 13.5 nanometers—one ten-thousandth the width of a human hair.

It’s difficult to think of another company that is simultaneously this important and yet this unknown to the public at large. If Veldhoven vanished tomorrow, our version of capitalism—our cellphone-toting, remote-working, Netflix-binging, online-buying, cloud-storing, smart car-driving, Internet-of-Things-ing capitalism—would judder to a halt. ASML isn’t a monopoly, but its market depends upon its technology to a degree that can almost be discomfiting.

ASML provides a window not just into our silicon-chipped world but also into a business that has to ride waves of technological and social change. The company’s singular status places it squarely in the path of any economic or geopolitical turbulence that affects the chip industry. It is, for example, caught between the US and China in their ongoing trade war. And it is, of course, feeling the heat of the chip shortage.

To expand its capacity to meet demand would take two years, Peter Wennink, ASML’s chief executive, said. “So we’re just trying to get more people to do more things faster”—that is, to assemble photolithography machines out of their hundreds of thousands of parts, test them, break them down again, fly them to semiconductor plants in Taiwan or South Korea or the US, build them back up, and get them running, so that the plants can try to meet our near-insatiable appetite for chips. No pressure.

How it works

- The heart of the photolithography process is the “mask,” a sort of master blueprint: a flat plate scored through with lines and holes that lay out the complex network of circuits on a chip. Companies design these networks based on the needs of their devices. Apple, for instance, maps out its circuitry and asks the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) to manufacture chips bearing those designs.

- Light falling on a mask passes through the lines and holes in the precise pattern of circuits. Below the photomask is the “substrate”—the topmost layer on the surface of a semiconductor wafer. The substrate is designed to be chemically sensitive to light, so when light falls on the wafer through the mask, it “prints” the pattern onto the wafer.

- The shorter the wavelength of light, the finer these patterns can be—and the finer the patterns, the greater the complexity of circuits that can fit onto a chip, and the more that chip can do. ASML is the only company in the world that makes photolithography machines generating EUV light.

- Producing this light is difficult. A source within the machine releases 50,000 drops of molten tin each second. A laser heats these up into plasma, which emits just the kind of EUV needed. But these processes make the machine so hot that a perfect vacuum has to be maintained within the chamber, to control the temperature.

A brief history

1959: The first chip with integrated circuits is fabricated. The same year, the photolithography process receives its first patent in the US.

1984: Philips, a chipmaker, uses its expertise in optical technology to set up ASML, a joint venture with another company named Advanced Semiconductor Materials International. The first employees sit in the corner of a leaky factory hall and in temporary Portakabins in the Dutch town of Veldhoven.

1988: ASML is spun off into an independent company.

1995: ASML is listed on the Amsterdam and New York stock exchanges.

2000s: ASML begins research and development on EUV machines. The development gets so costly and complicated that ASML invites some of its customers—Intel, Samsung, TSMC—to buy stakes in itself, so that the money can be used to fund research.

2010: ASML ships a prototype EUV machine to a client’s research facility in Asia.

2016: The first truly production-ready EUV machines ship out to ASML clients.

2018: ASML’s market share rises to over 60%, double what it was in 2005.

2020: Of the 258 photolithography machines ASML sells, 31 are EUVs. ASML expects its EUVs to earn three-quarters of all its revenue by 2025.

13.5 nanometers: Wavelength of the extreme ultraviolet light in an EUV

50,000: Drops of molten tin released every second in an EUV

$120 million: Cost of an EUV

$1 billion: Cost of a facility to use EUVs to manufacture semiconductor chips

$13.2 billion: ASML’s revenue in 2019

543 billion: Chips imported by China in 2020

$30 billion: Latest round of investment by China into developing a domestic semiconductor industry

$60.6 billion: Estimated losses in revenue for the automotive industry as a result of the global chip shortage

The geopolitics of it all

Semiconductor chips are so important today—in how they’re used, in where they’re made—that they’ve become part of geopolitical strategies. Most of the world’s chips are made in Taiwan, South Korea, or the US. But since the world’s largest consumer of chips is China, this presents an economic lever to use against Beijing.

The US government and other Western countries have grown worried about what China might use cutting-edge chips for, and what surveillance technology it might install on any chips it sells to the world. Additionally, in the ongoing tussle of economic one-upmanship between Beijing and Washington, the US wants to keep China dependent on non-Chinese chip vendors. So under US pressure, chipmakers are restricted from selling their products to Huawei. Along similar lines, ASML’s EUV was placed on the Wassenaar list, a multilateral regime that controls the export of several critical technologies to non-member states such as China.

As a result, China cannot manufacture the most sophisticated chips in the world, much as it wants to. Its state-owned chipmaker, SMIC, was founded in 2020, but has to work with older-generation photolithography machines. It’s difficult for China to set up a company from scratch to make something as complex as an EUV.

Still, the possibility always exists that China will seed and grow photolithography machine manufacturers—becoming not just self-sufficient in chips but competitive with ASML. “The government just put an absurd $30 billion into this in its latest economic plan to catch up,” Velu Sinha, a partner in Bain & Company’s technology practice, said. “It isn’t Game Over—it isn’t that China will never get there.”

Pop quiz

Which of the following does not use semiconductor chips?

🚗 The first generation Tesla Roadster, produced in 2008

☀️ An LED tanning-bed lamp

💳 Debit cards

👟 Nike Vaporfly shoes

🎸 Audience wristbands at Coachella

Keep learning:

- The global semiconductor backlog may last through the end of 2021.

- The biggest culprit for the shortage of chips is the state of the global semiconductor industry.

- Samsung wants to put a chip into everything.

- A Taiwanese semiconductor titan is at the nucleus of the US-China tech fight.

- Apple and Qualcomm settled a lawsuit between them. So why was Intel the loser?

- Answer 🔑 : Nike Vaporfly Shoes remain—for now—chip-free.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a conductive end to your week,