For members—Crypto’s controversial clique

Hi Quartz member,

Hi Quartz member,

Coinbase founder Brian Armstrong got two big things right: He understood early on that bitcoin was a trillion-dollar opportunity, and that regular people would need a simple, regulator-friendly way to access it. That vision became Coinbase, and when the biggest US crypto exchange went public in April, it made 38-year-old Amstrong one of the richest people on the planet.

In typical tech-company fashion, Coinbase has a lofty mission: “to use cryptocurrency to bring economic freedom to people all over the world.” A spokesperson says the exchange does that by promoting free trade, enforcing property rights, enabling freedom of contract, providing access to stable currency, and through its nonprofit charity, GiveCrypto.

But it’s an open question whether bitcoin and its ilk will become a genuine alternative to fiat currencies, gold, and finance as we known it, or remain little more than a digital gambling den. In the meantime, Coinbase faces mounting competition abroad and in cyberspace.

OK, get out your crypto wallet and jot down your private key. We’re talking about Coinbase.

Master of Coin

When Coinbase went public in April, some saw it as a critical moment for the crypto sector the nine-year-old company helped build. Its listing on Nasdaq, with regulatory blessing for the offering and the invitation for deeper scrutiny of its financials, would help legitimize the virtual assets and crypto projects of different stripes and flavors, the thinking went.

It was also a moment of validation for Armstrong himself. The former Airbnb engineer reportedly first heard about bitcoin in 2010, two years after the technical specifications for digital cash appeared on the internet.

Armstrong made two important bets when he started Coinbase with seed funding from Y Combinator. One was that the exchange would keep and protect users’ private keys—a secret code that’s necessary for bitcoins to be spent. The other was that he would cooperate and work with government regulators.

These choices were controversial in the crypto world. The whole point of bitcoin and other virtual assets, for some purists, is that you don’t need a bank or other intermediary to use it. Bitcoin is like cash—with the associated risks and benefits. You can lose your code or someone can steal it. At the same time, no bank, exchange, or government can stop you from using it.

Many of bitcoin’s early supporters had rebellious or libertarian views, and some in the community also bristled at playing nice with the regulatory authorities. While some crypto enthusiasts saw themselves as renegades, Armstrong figured it was a better move to portray Coinbase as an exchange that worked within the system.

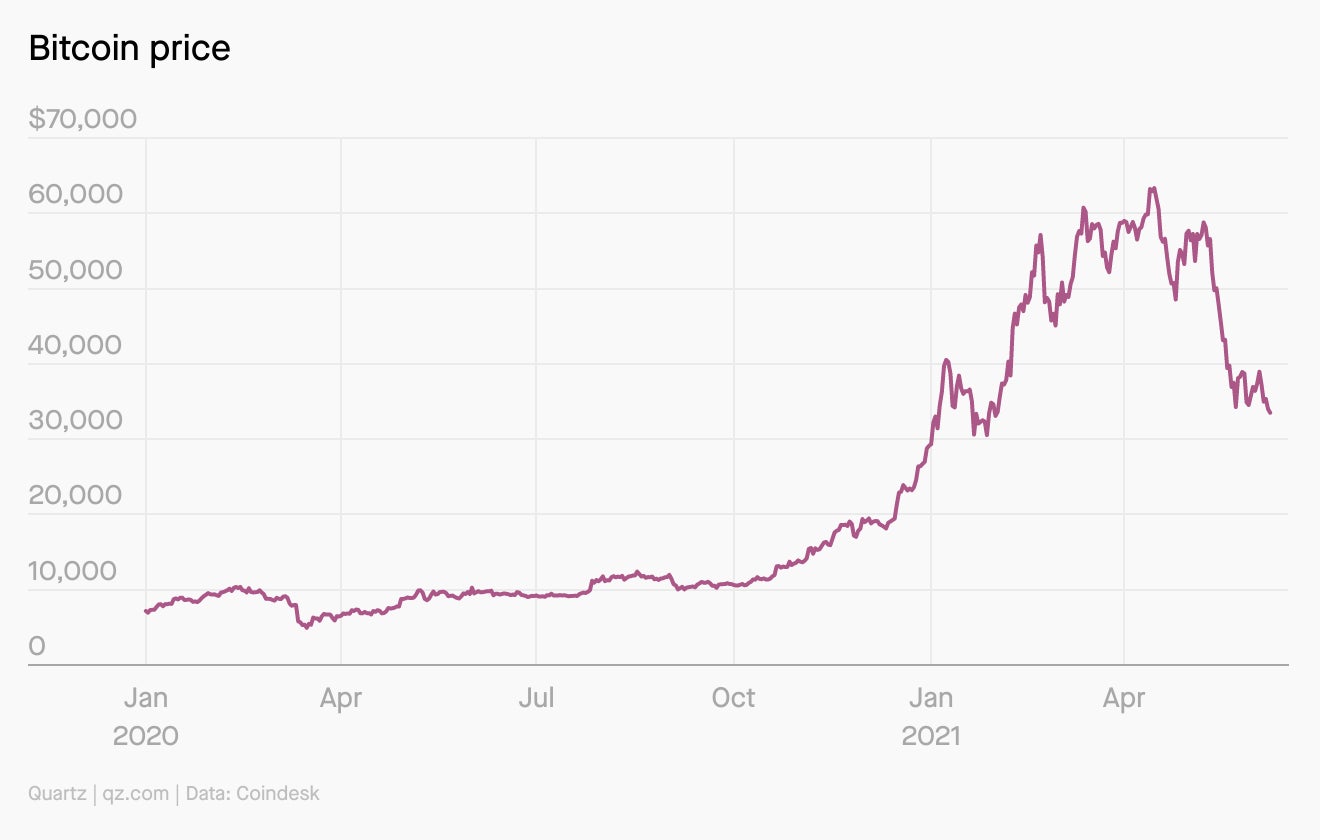

His instincts have so far served him well: Armstrong correctly understood that regular people would need an easy on-ramp to the mysterious and technical world of crypto. After multiple booms and busts, Bitcoin is trading for around $34,000, up from $100 or so in 2014. Coinbase makes a nice profit from the $30 billion to $300 billion-plus in trading volume (pdf) that takes place on its platform each quarter.

Coinbase is now valued by the stock market at more than $46 billion, and it’s the largest exchange in the US. The company says it raked in $771 million in net profit during the first three months of the year, four times that of the previous quarter.

What could possibly go wrong? Coinbase faces competition from the likes of Binance, the world’s largest crypto exchange, as well as decentralized exchanges like Uniswap, which handle more trading activity than Coinbase does.

And even though Armstrong’s exchange is meant to play nice with regulators, Coinbase technically falls between the gaps of oversight by the Securities Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission—for now. Tighter regulation could crimp profits or more.

QZ&A

Jeff John Roberts wrote the book on Coinbase—literally; it’s called Kings of Crypto, and it chronicles the exchange’s rise from Y Combinator startup to the biggest market for virtual assets in the US. Quartz spoke with Roberts to find out the juicy details.

On the Coinbase founder and media attention:

On Armstrong’s leadership style:

People in the industry underestimated Armstrong:

On Armstrong becoming a more polished speaker:

Where are they now?

👨 Coinbase co-founder Fred Ehrsam left the exchange in 2017 but is still on the board. He co-founded Paradigm, a venture fund that invests in crypto startups.

👨 Olaf Carlson Wee became Coinbase’s first employee after a job interview with Ehrsam and Armstrong that included solving “a really brutal mathematics problem.” In 2016 he started Polychain Capital, a fund that invests in crypto.

👨 Charlie Lee was an early employee and spent about four years at Coinbase as an engineer. In 2011 he created Litecoin, an alternative to bitcoin that has a market value of around $18 billion.

👨 Ben Reeves was also a co-founder of Coinbase, but he and Armstrong split up over a disagreement about whether Coinbase should hold and control users’ private keys. Reeves is the co-founder of crypto wallet Blockchain.

Quotable

“The price of bitcoin is purely a function of the market’s imagination. That is, unlike the prices of the S&P 500 or a commodity like crude oil, there is no set of fundamentals that gets in the way of what bitcoin’s price can be. If enough people wake up in the morning thinking that the price of bitcoin should rise, and act on it, then it will rise.”—JP Koning

Bitcoin has never really caught on as a means of payment. But some think it could be a digital goldmine, while others see it as mainly a speculative asset par excellence.

$17 billion: Value of CEO Armstrong’s stake in Coinbase after its IPO

$1.8 billion: Coinbase revenue during first three months of 2021

$47 billion: Coinbase market capitalization (down from about $86 billion went it went public)

$26 billion: Exchange operator Nasdaq’s market capitalization

1,300: Number of questions Coinbase received ahead of its pre-IPO Reddit AMA

440,000: Bitcoin’s approximate record for number of daily transactions

386 million: Average number of daily transactions on the Visa card network in 2020

Coinbase controversy

Armstrong opened a can of worms in September with a blog post titled: “Coinbase is a mission focused company,” in which he said the exchange would focus on its mission to “create an open financial system for the world” and warned that Coinbase would not be a place to “debate causes or political candidates internally that are unrelated to work.”

Armstrong described his vision in simple terms: Corporate social activism is likely to backfire by dividing employees, and distracting enterprises from their true purpose. His post said Coinbase should not be expected to represent employees’ personal beliefs externally, or to take on any activism outside of its core mission. The company later offered an exit package to workers who disagreed with the policy.

The timing of Armstrong’s post—it was published as the US contended with a racial reckoning sparked by the killing of George Floyd—seemed short-sighted and incredibly tone deaf to many. Then late last year, the New York Times reported that 15 Black Coinbase employees had left or been pushed out in 2018 and 2019; many had reported racist or discriminatory treatment to human resources on their way out. Black employees said they had been stereotyped in front of their colleagues, described as less capable, and passed over for promotion.

A Coinbase spokeswoman told the Times that the company “does not tolerate racial, gender, or any other forms of discrimination.” The company then took the unusual step of emailing employees before the article ran, questioning its accuracy, and pre-emptively posting the email publicly.

Keep learning

- Coinbase’s listing may have marked a peak for bitcoin (Quartz)

- Seven secrets from Coinbase’s early days (Decrypt)

- How Armstrong made crypto trading as easy as sending email (WSJ)

- Five percent of Coinbase staff walked away from its “apolitical” future (Quartz)

- Elon Musk and Cathie Wood disagree on bitcoin’s climate impact (Quartz)

- The world’s largest crypto exchanges have invested in India despite unfriendly policies (Quartz)

- A manager and employee compare notes on Basecamp’s controversial memo (Quartz)

- Elon Musk “explains” Dogecoin (Saturday Night Live)

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a speculative end to your week,