Fish sticks: How consumers got hooked

Caught up in nostalgia.

Caught up in nostalgia

Suggested Reading

The year was 2020, and thanks to a novel coronavirus, even a simple trip to the grocery store was suddenly a harrowing experience. Many homebound diners turned to their freezers to find comforting, easy-to-make meals. Those (we) hapless souls pulled out the unlikeliest of frozen heroes: the fish stick.

Related Content

In the US, Gorton’s sold 58 million more fish sticks than usual from March through July 2020. In the UK, fish fingers were Birds Eye’s fastest-growing product of the year, with sales up 23%. Germany-based Frosta’s fish finger sales increased 50% in the first half of 2020. And even as shoppers cut back on their canned tuna purchases in 2021, they kept buying frozen seafood.

That’s not bad for a “futuristic” 1950s food consumers never asked for in the first place.

What’s got today’s shoppers hooked? Let’s take the bait.

By the digits

25,459 metric tons (28,064 tons): Volume of US fish stick production in 2019, down from a high of 37,404 metric tons (41,231 tons) in 2008

2 billion: Fish fingers consumed in Germany every year

7 million: Fish fingers made daily at Germany’s largest production facility—if laid end to end, they would measure 800 km (497 miles); a year’s production is enough to circle the Earth 3.5 times

65%: Percentage of fish a fish finger must contain in Germany and Austria; in France and eastern Europe, the percentage can be as low as 52%

£187 ($227): Cost of the gold-crusted fish finger sandwich Birds Eye made for Queen Elizabeth II’s 90th birthday

$.49-.53: Price of a package of Birds Eye fish sticks when the product was introduced to the American market in 1953

Origin story

A solution to a problem consumers didn’t know they had

Post-World War II, larger fishing boats with onboard refrigeration and processing allowed US fleets to catch a lot more fish. Unfortunately, not many people wanted to buy it. Meat was no longer rationed, and then, as now, fish had a reputation for being smelly and difficult to prepare.

One newfangled product that fish companies hoped would excite consumers was “fishbricks”—tubs of frozen fish filets, packaged like ice cream, that allowed housewives to scoop out the amount they needed for each meal. Needless to say, fishbricks were a flop.

The industry’s winning innovation came from Birds Eye, the frozen food company founded by Clarence Birdseye, who famously developed his method for flash freezing food after observing Inuit preservation techniques. Birds Eye’s parent, General Foods Corporation, applied for a patent for its “production of fish product” in 1952, and fish sticks hit the market in 1953. Competing products from Gorton’s (the eventual US market leader) and Fulham Brothers followed close behind.

Manufacturers soon discovered fish sticks had global appeal. Birds Eye introduced them to the UK in 1955—renamed as fish fingers based on a poll of female factory workers—and within 10 years they accounted for 10% of UK fish consumption. Fish fingers arrived in Australia in 1956 and were first sold in Germany in 1959.

Food for your ears

Like this topic? So do we.

All aboard, podcast lovers! Season 4 of the Quartz Obsession is about to cast off.

Explain it like I’m 5!

How fish sticks are made

The process for making fish sticks is more or less the same as it was in the 1950s. After the fish are caught, they are turned into boneless, scaleless, headless filets, which are layered into giant blocks and frozen.

At the fish stick factory, band saws cut the frozen blocks down to fish stick size. The sticks are enveloped in a thin coating of batter, then covered with breadcrumbs or other dry breading. Next, the fish sticks are briefly deep fried—long enough to solidify the breading but not long enough to cook the fish—and immediately refrozen, before they are packaged and shipped out to stores, restaurants, and cafeterias.

Pop quiz

Which dictator almost sank Gorton’s?

A. Adolf Hitler

B. Benito Mussolini

C. Francisco Franco

D. Josef Stalin

Find the answer at the bottom of the sea/this email!

Person of interest

Captain Birds Eye gets a glow-up

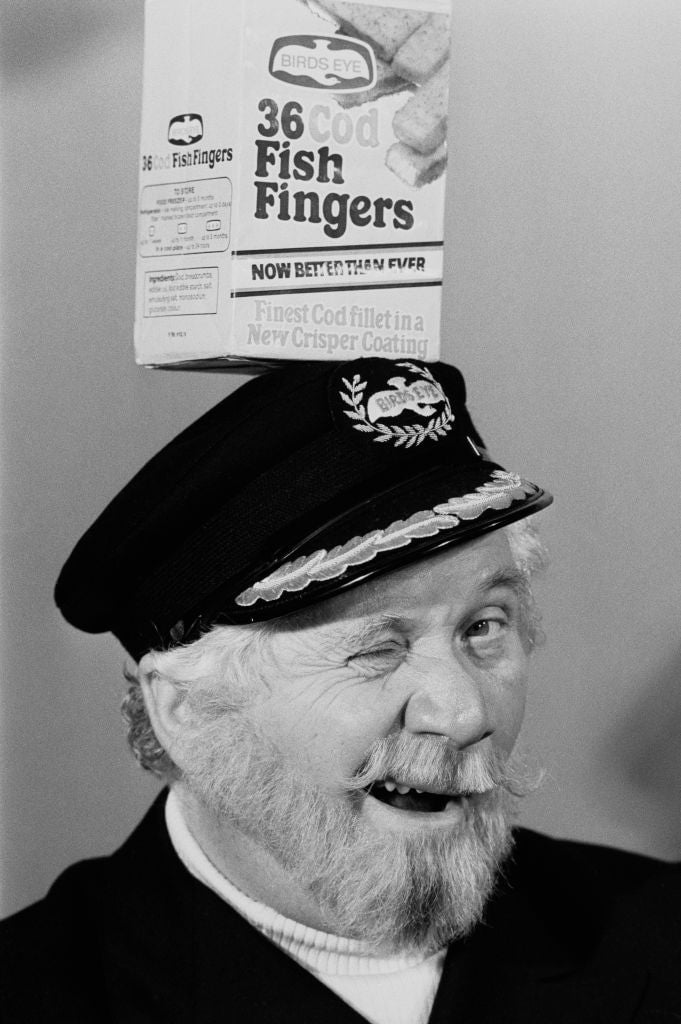

Since 1967, the face of Birds Eye in the UK has been Captain Birds Eye, a friendly, Santa-like seaman with a passion for fish fingers. He was played by actor John Hewer (pictured above) for more than 30 years.

Once Hewer retired, Birds Eye cast 31-year-old Thomas Pescod as the new Captain, but Brits didn’t take to the younger actor, and in 2002 he was replaced with a more mature-looking Martyn Reid, who had the job through 2007. Captain Birds Eye disappeared from the scene until 2016, when the company brought back the spokesman and cycled through a series of three similarly grandfatherly figures.

In 2018, Birds Eye made the controversial decision to hire a sexy Italian actor—who bears a strong resemblance to the original Dos Equis “most interesting man in the world”—as the latest Captain. He’s even had his own calendar, novelty men’s fragrance, and sustainable swimwear line.

Fun fact!

In a 2015 survey, one in five young adults in the UK believed fish fingers are made from the fingers of fish.

The way we 🎣 now

When fish sticks get stuck

Today’s fish stick industry is a global operation, and that has caused headaches for US suppliers and manufacturers. In 2018, they were caught up in the US-China trade war as both sides ratcheted up tariffs on seafood (pdf). A lot of the Alaskan pollock that goes into American fish sticks is processed in China and re-exported to the US, and those products were initially on the US tariff list.

At the same time, Russian pollock—which accounted for 50% of the fish in US school-lunch fish sticks in 2017—was excluded from Trump’s tariffs, allowing it to gain even more share in school cafeterias. (Lobbying from Alaska senator Dan Sullivan means that today only US pollock can be used.)

More recently, US seafood companies ran afoul of a 100-year-old maritime law that says cargo shipped between two US locations must be transported on US vessels, unless at some point in that journey it goes by rail within Canada. Since 2012, some companies had been using a 100-foot “railroad” located entirely within a New Brunswick port to get around the restriction. A US crackdown on the loophole in September 2021 trapped 26 million pounds (12 million kg) of Alaskan pollock in Canada. A judge allowed imports to resume the following month.

Million-dollar question

Are fish sticks sustainable?

By and large, the fish used in fish sticks is caught sustainably. A 2018 analysis (pdf) by the UK’s Marine Conservation Society found that 85% of the 48 brands tested used fish from “Best Choice” sources, while 60% carried a seal of approval from the nonprofit Marine Stewardship Council. German brand Frosta even stopped making fish fingers for around 10 years because it couldn’t source enough MSC-certified fish, and only restarted production in 2014.

However, as with most questions about sustainability, it’s complicated. One recent study notes that the fuel-guzzling ships that transport the fish to processing facilities and the trucks that deliver the final product to stores contribute significantly to fish sticks’ overall carbon footprint.

Some companies are working to bypass the ocean entirely. Good Catch makes plant-based fish sticks that mimic the texture and taste of the real deal, while the owner of Birds Eye in the UK, Nomad Foods, has partnered with US-based BlueNalu to develop lab-grown fish products.

Poll

What’s your favorite stick-based food?

- Fish sticks

- Mozzarella sticks

- Pixy Stix

- An actual stick (I’m a dog)

Stick up for your opinions. Tell us your answer!

💬 let’s talk!

In last week’s poll about vertical farming, avocados narrowly edged out potatoes as the crop you’d most like to see go vertical, though 16% of you were pushing for cheese, somehow.

💌 Fantastic news—we had a glitch that meant your emails weren’t getting to us. All is well now, and we’d love for you to get back in touch.

Today’s email was written by Liz Webber (grew up eating Van de Kamp fish sticks), and edited by Susan Howson (dreams of that classic slightly soggy crunch) and Annaliese Griffin (toured the Gorton’s fish factory on vacation as a child in Gloucester, Massachusetts).

The correct answer is B. Benito Mussolini. In the 1920s, Gorton’s delivered an order of $1 million worth of salt cod to Italy, which Mussolini refused to pay for. Clarence Birdseye moved to Gloucester soon after and saved the day with his new flash freezing techniques.