Hi, Quartz members,

Whoever said “There’s no such thing as bad publicity” would have had a change of heart after working on Boeing’s PR team over the last few months.

Barely a week ago, a Boeing 747 cargo plane had to make an emergency landing after fire broke out in one of its engines; in a spectacular video captured by someone on the ground, the plane seemed to be coughing flames out of its rear. A couple of days later, a nose wheel detached and rolled away from a Boeing 757 just as it prepared for takeoff in Atlanta. An All Nippon Airways flight suffered a crack in its windshield; a Boeing scheduled to carry US Secretary of State Antony Blinken from Switzerland to the US was grounded because of an oxygen leak.

Compared to what happened earlier in January (a door plug blowing off midair during a terrifying Alaska Airlines flight involving a 737 Max 9 plane) or last September (engine fire; burst tires; again a 737 Max 9), these may have been less dramatic incidents. But they served nonetheless to continue the cavalcade of unfortunate news surrounding Boeing—and, in particular, its Max planes.

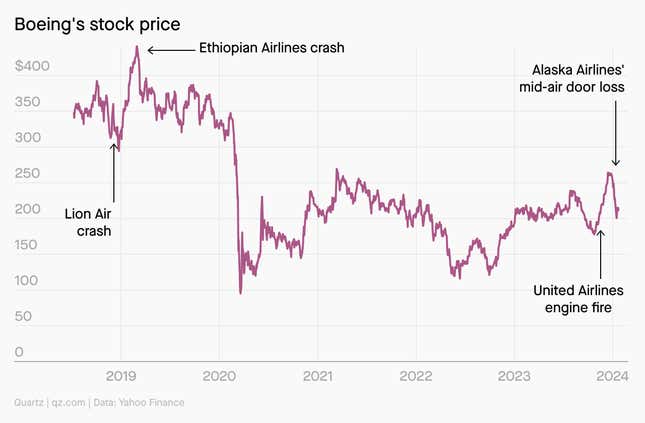

You’ll remember these planes from even worse news in the not-too-distant past. In 2018, a Lion Air flight on a Max plane crashed into the Java Sea, killing 189; a few months later, an Ethiopian Airlines flight crashed just after taking off from Addis Ababa, killing nearly 160 people on board. After these twin accidents, airlines grounded their Max planes for nearly two years, costing Boeing more than $20 billion in compensation and other expenses and perhaps as much as $67 billion in lost Max sales.

The Federal Aviation Administration is currently investigating Boeing’s manufacturing practices, and US airlines have grounded a number of their Max planes. Air travelers are checking the model of their planes while booking flights. The whole debacle is sending ripples across the entire industry. It’s a crisis—so how is Boeing holding up?

CHARTED

QUOTED

“I think the Max 9 grounding is probably the straw that broke the camel’s back for us. We will at least build a plan that doesn’t have the Max 10 in it.”

— Scott Kirby, the CEO of United Airlines, which grounded 79 of its Max 9 planes following the Alaska Airlines incident. United had agreed to purchase 277 Max 10 planes from Boeing, with the option for another 200.

A FIELD OF TWO

To be sure, the movement of a stock doesn’t capture everything about a company. But it throws up intriguing questions—particularly in the case of Boeing.

A faulty product from an aircraft manufacturer is very different from a faulty product from a toy company or a film studio. Lives aren’t on the line with a defective Hungry Hungry Hippos or a flabby Marvel movie. A Boeing plane isn’t entirely its own product, of course; it’s filled with components made by other companies, such as engines and tires. (Indeed, critics have pointed out that Boeing’s increased emphasis on outsourcing as much of the airplane as possible, in a quest to drive up profits, is partly to blame for its Max crisis.) But the label on the plane is still Boeing’s. You wouldn’t be blamed for thinking that crashes or dangerous accidents would lead to an absolute bloodbath in its stock price.

But that hasn’t tended to happen; any slides in stock price have been minimal and eventually—sometimes even quickly—contained. (The current decline, admittedly, is still in progress.) Analysts have noted this in the past as well. What gives?

One answer lies in the nature of the aircraft manufacturing sector: a duopoly dominated by Airbus and Boeing, giving airlines little alternative but to keep buying from these companies. Mere days after the Alaska Airlines mid-air door blowout, and even as loose bolts are being found in many Max planes, India’s Akasa Airlines placed an order for 150 of the aircraft. Boeing is so essential to the aerospace industry that the FAA can’t easily take the step of grounding its planes or halting production. During its ongoing investigation, the FAA allowed Boeing to keep making Max planes at its current pace, and only prohibited the company from stepping up production. As long as airlines are buying, the stock will not bottom out; it’s telling that, over the last five years, the most precipitous drop in the stock price came in the early months of the pandemic, when no one was sure when flights would resume.

This duopoly exists for a very good reason: Planes are time-consuming and expensive to build. Planning for Boeing’s 777X started nearly 15 years ago, and the plane still hasn’t been put into commercial service. The only major company to start making planes of its own, in recent years, is the state-funded Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC), which launched its C919 into commercial service last year. COMAC may have received anywhere between $49 billion and $72 billion in state support, according to the Center for Strategic & International Studies—and it isn’t even remotely a rival to Airbus or Boeing yet. When that’s the volume of capital needed to enter the field, it’s difficult to see the duopoly dissolving any time soon.

ONE ✈️ THING

While Boeing is still very much one of the two big players in commercial aviation, its revenues have declined, even as Airbus’s have climbed. It has nearly $40 billion in debt, arising partly out of the pandemic’s impact on airlines. Unlike other struggling US companies, though, one prospect keeps popping up whenever Boeing’s woes are discussed: nationalization. It’s vital for the US to have a competitive homegrown plane-manufacturer. Observers maintain that Boeing is already, at the very least, “a state-backed national champion,” with a large share of revenues coming from the US government, which also encourages airlines to buy its planes. And nationalizing an airplane giant wouldn’t be outrageous; COMAC is an extreme example, but even Airbus is one-tenth owned by the French government. It’s a sign of how central aviation is to our world that it’s easier to see the US government nationalizing Boeing than it is to envision the fall of Boeing altogether.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have an accident-free weekend,

— Samanth Subramanian, Weekend Brief editor