Hi Quartz members!

Carbon markets are proving one of the most divisive issues at COP26. Activist Greta Thunberg stormed out of a Nov. 3 meeting about them—shouting “no more greenwashing!”—but many officials argue they could unlock billions in funding to accelerate the low-carbon economy… if everyone can agree on some highly technical and politically sensitive details.

Negotiators are hung up on what’s known as Article 6, which sets guidelines for how countries can buy or sell credits generated through emissions-reducing projects. Article 6 outlines two types of carbon markets, the first consisting of trade deals between governments that agree to buy and sell carbon credits (or allow private entities within one to sell credits to the government of the other). This type of carbon market already exists: California, Canada, Japan, South Korea, and Switzerland have all purchased offsets derived from projects in other countries, and then counted those toward their domestic decarbonization targets.

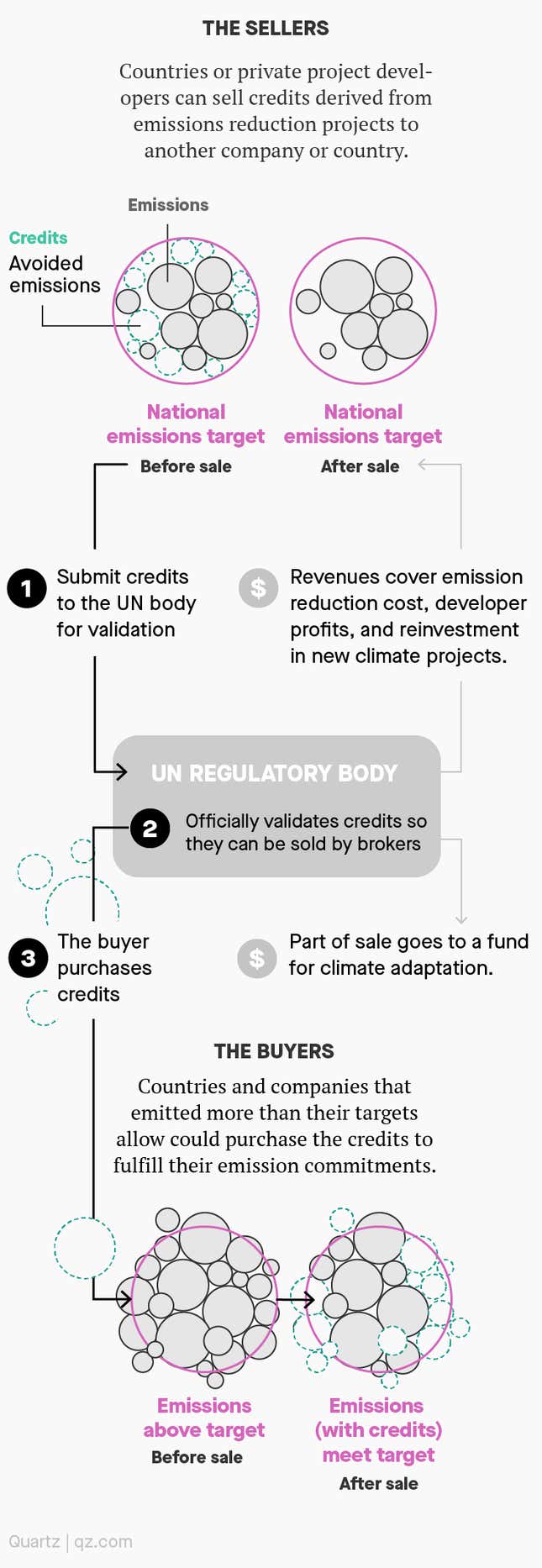

But the second kind of carbon market would be a true global marketplace, regulated by the United Nations, and would replace a smaller market authorized by the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. In this new market, governments or companies could pitch or purchase credits via a UN supervisory board that would effectively act as an exchange. Project developers would need government approval to pitch, and some of the proceeds could be channeled into a fund for low-income countries. One big challenge for this market: It’s not clear who the buyers would be.

Both types of markets currently suffer from a lack of clear standards, which has made them largely ineffective up to now. A draft text of Article 6 circulated this week encompasses possibilities that could fix some of those flaws (or not). But don’t get your hopes too high: Negotiators have failed to agree on Article 6 rules in the last four COPs; there’s no guarantee they’ll succeed this time.

The backstory

- Carbon markets turn emission reductions into tradable assets. These credits are generated from emission-reduction projects (a solar farm or forest-conservation easement, for example) or pollution allowances allocated by government cap-and-trade systems. The credits are then sold to buyers, often private companies or governments, looking for cost-effective ways to cut emissions.

- Buying credits is often cheaper than reducing all emissions. Because greenhouse gas pollution is global—it affects the atmosphere equally no matter where it’s emitted—the climate benefit is the same no matter where emissions are avoided or removed. Theoretically, carbon-market revenue funds efforts that wouldn’t happen otherwise (a concept known as “additionality”), opening up cheaper ways for countries and companies to lower emissions.

- Some carbon markets already exist. That includes legally mandated cap-and-trade markets for certain sectors in the US, Europe, and China, plus a booming market for voluntary offset credits bought by companies. But these aren’t perfect. Many offsets don’t really correspond to the stated volume of emissions, aren’t permanent, and/or are derived from projects that would have happened even without the carbon market (and thus don’t represent genuine climate action on the part of the buyer).

How it could work

What to watch for next

- Proving “additionality.” Additionality is a major problem in existing voluntary carbon markets: Should a forest conservation project really generate carbon credits if it faces no actual threat of being cut down? Negotiators need to agree on how a selling party should determine baselines for different types of projects.

- Matching emissions vs. reducing them. Language like “overall mitigation in global emissions” would require the market to do more than offset emissions in one country with reductions in another. The idea is that carbon credit buyers should receive fewer credits than they pay for, such that trading activity proactively reduces net emissions. The draft text pegs that tax as low as 2% or as high as 30%, with developing countries arguing for the higher end.

- How to prevent double-counting. If both the buying and selling countries could count sold credits toward their own emissions targets, it would delegitimize the market.

- “Share-of-proceeds.” Some negotiators argue that a share of each trade should be diverted into a fund that developing countries could tap for adaptation. The US and other rich countries are pushing for this to be excluded when trades are conducted bilaterally rather than through a UN-administered marketplace.

- Crediting the original credits? Negotiators need to figure out what to do with credits from that smaller carbon market piloted under the Kyoto Protocol. Countries like Brazil and India want to continue selling those credits. Others argue those credits are outdated and should be tossed.

We’re in the market for feedback. How are you liking Quartz’s new member-exclusive emails? Let us know by taking this (brief!) survey.

One 🛢️ thing

While the carbon-market fight is ongoing, the most impactful COP26 announcement of the past 48 hours has to do with fossil fuel phaseout. More than 20 countries and institutions, including the US, agreed on Nov. 4 to end international development financing for most oil and gas projects outside their borders by the end of next year. China and Japan, two of the biggest financiers of overseas fossil projects, weren’t on the list.

Need more COP26 intel? We’re on the ground in Glasgow, and sharing updates every other day in our Need to Know: COP26 newsletter.

Quartz stories to spark conversation

⛏️ Even bitcoin is getting hit by the supply chain crisis

🧯 This is how the Fed will confront climate change

📈 Inflation is expected to run hot well into 2022

🤔 China is invoking an American economist on productivity

🏘️ How Zillow got rocked by the housing market

💊 Hollywood is remaking The Matrix franchise as NFTs

🥽 The metaverse will mostly be for work

5 great stories from elsewhere

🐋 Are we about to talk to whales? Hakai Magazine explores the Cetacean Translation Initiative, which is using artificial intelligence to decode whalespeak.

🇨🇳 China’s “ideas man.” Palladium profiles political theorist Wang Huning, a Chinese Communist Party leader who has shaped Beijing’s vision for decades.

🔬 Time to revolutionize American science. The Atlantic diagnoses several paradoxes in the US science system, which together stifle speed, expertise, and creativity.

🕰️ Watching the clock. The Guardian looks at “time millionaires,” who focus on clawing back hours from work to spend on leisure instead.

💁♀️ Whither the plain female protagonist. LitHub examines a seemingly inescapable authorial instinct: to render all leading literary women as “hot.”

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a sustainable weekend,

—Tim McDonnell, climate and energy reporter (subsisting on mediocre cheese sandwiches and putting in about 12,000 steps per day in Glasgow)

—Amanda Shendruk, Things reporter (drowning in impenetrable UN acronyms)