Hi Quartz members!

The US is facing a shortage of 80,000 truck drivers, according to an October warning from the American Trucking Associations (ATA), an industry group representing big US trucking companies. It’s an alarm the ATA has sounded every year since 2005, but amid a global supply chain crisis, the argument is once again picking up steam. Executives at publicly traded companies referenced the “driver shortage” in at least 61 calls with investors over the past 30 days.

But the assertion that the US is suffering from the latest round of a 16-year truck driver shortage is misleading at best. About 2 million Americans work as licensed truck drivers, and states issue more than 450,000 new commercial driver’s licenses every year. In fact, it’s the most common job in 29 states.

The real shortage is of good trucking jobs that can attract and retain workers in a tight labor market. The annual turnover of drivers at big trucking companies averaged 94% between 1995 and 2017, according to ATA statistics. A third of drivers quit within their first three months on the job. Today, many licensed drivers can find better working conditions and pay elsewhere, including at factories, construction sites, and warehouses.

Economic theory suggests that when there’s a shortage of something—in this case, workers willing to drive trucks—prices (or wages) will rise and more people will be motivated to supply it. Eventually, the shortage should abate. Yet the “driver shortage” rhetoric has been repeated by the trucking industry since the late 1980s. How could such a clear shortage persist for three decades in a market economy?

In 2019, two economists for the US Bureau of Labor Statistics set out to investigate the mystery of the perpetual driver shortage. They found that the labor market for trucking works about the same as the labor market for all sorts of blue-collar work: Differences in pay entice workers to enter the truck driving industry—and leave it for better opportunities. “There is thus no reason to think that, given sufficient time, driver supply should fail to respond to price signals in the standard way,” the authors wrote.

In other words: Raise wages, and the workers will come.

The backstory

- Trucker wages can’t compete. They’re rising at about the same rate as overall US wages, which makes it harder for trucking to compete against other blue-collar employers also hiking pay in manufacturing, construction, and logistics.

- Raising wages is already helping. Trucking wages are up 6.7% since April, and the number of working truckers is, accordingly, up 7%. When trucking companies increased wages in the run-up to the 2020 holiday shopping season, trucking employment went up. When trucking companies cut wages immediately after, employment went down.

- Driver pay is only part of the equation. The US also needs infrastructure improvements. As it stands, drivers are forced to wait in lines at ports that weren’t built to handle the volumes of cargo they’re currently seeing. They also waste time searching for overnight parking and wind up ending their driving days early when they happen to find a spot. These challenges make the job more aggravating and less efficient.

Keep on trucking?

Life as a long-haul trucker isn’t easy. Aside from the tedium of driving on highways all day, truckers deal with the myriad hassles that come with their nomadic lives.

😴 Many long-haul truckers spend the night in “sleeper cabs”—small bedrooms tucked behind the driver’s seat—and pay $15 to shower at a truck stop.

⏲️ US law limits truckers to 11 hours of driving a day and 60 hours a week; when their time is up, they have to stop wherever they are, no matter if there’s food, lodging, or bathrooms nearby.

💰 Most truckers get paid by the mile, meaning all the time they spend sitting in traffic, waiting to load and unload, or looking for parking for the night is unpaid.

💊 Trucking comes with health risks: Drivers sit all day and have limited dining options. Nor is visiting a doctor or filling a prescription along a truck route an easy task.

What to watch for next

- The holiday season. Trucking companies are already giving drivers splashy pay raises of up to 25%, offering bonuses of up to $1,000 per day for drivers who get stuck waiting in lines at ports, and guaranteeing minimum salaries. But there are still more open jobs than workers willing to drive.

- Expanding the hiring pool. Less than 7% of truck drivers are women—a severe limitation for an industry eager to attract more workers. Trucking companies have been taking pains to change that through efforts that are sometimes laudable (tuition subsidies for driving courses) and sometimes laughable (buying trucks with automatic transmissions, on the assumption that women can’t drive stick). A record number of women are now entering the industry, but often finding it wasn’t built for them.

- Teen drivers hitting the road. Industry groups have long lobbied Congress to lower the minimum truck-driving age of 21. And sure enough: Tucked into the recently passed US infrastructure bill is an apprenticeship program that would allow trucking companies to hire drivers as young as 18 for long-haul routes.

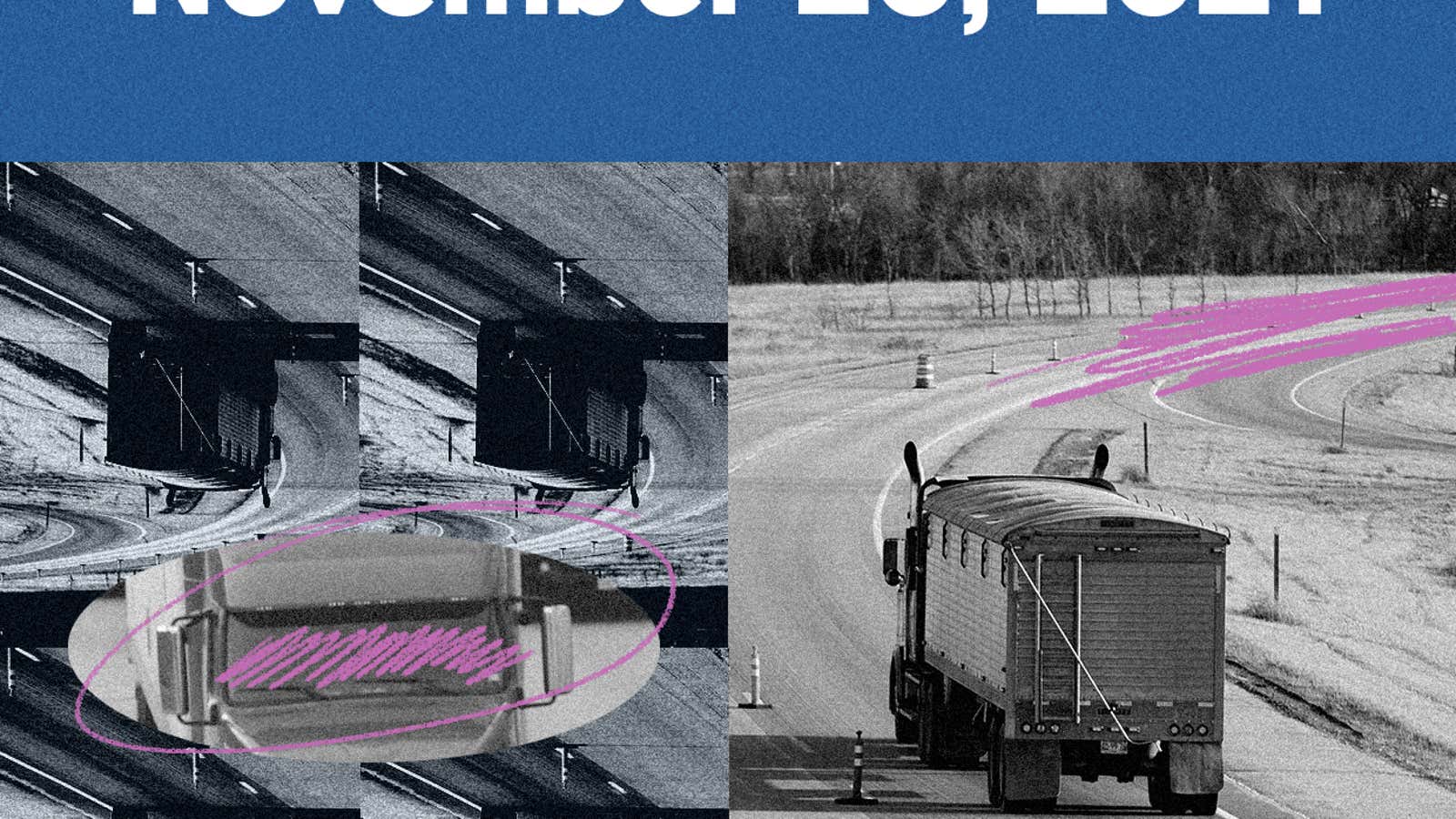

- Autonomous-trucking pilot programs. A handful of US startups are testing self-driving trucks (mostly in the southwest, where state highway laws are lax). Amazon-backed Aurora and Google-owned Waymo are already hauling freight between Houston and Dallas, Texas—with a human driver onboard to keep an eye on things. Meanwhile, Silicon Valley startup Plus announced in August that its autonomous truck had safely navigated Chinese highways without a human onboard at all.

- More non-truck delivery options. With ports jammed, rail yards in disarray, and trucking under-staffed, the idea of using long-range cargo drones to transport boxes no longer seems so far-fetched. This year, startups building autonomous drones to carry passengers and packages have raised $5.1 billion. That’s up from $1.1 billion in 2020, and compared with just $438 million for the entire decade between 2009 and 2019.

One 🚢 thing

One more job keeping the global supply chain moving: seafarers, who cross borders for a living to do their work on cargo ships. While the pandemic is driving demand for seafarers, they’re also caught in a patchwork of covid-era border restrictions. Seafarers are tied to the vaccine constraints of the countries they come from, which means some can’t get onboard a boat, while others are stuck at sea.

Quartz stories to spark conversation

💀 After COP26, climate goals are on life support

📈 Guess how much prices on common grocery items are up

🥽 China sees the metaverse as the next internet battleground

🎓 Reference letters perpetuate inequity. Let’s end them

🇮🇳 India’s startup ecosystem doesn’t need China

🏠 US home builders can’t get houses up fast enough

🐦 Finance Twitter is getting its own Dow Jones Index

5 great stories from elsewhere

🔌 How to stay in charge. The Verge interviews the CEO of a major seller of phone chargers and battery packs about hawking electronics in the age of Amazon.

🐯 Inside Tiger Global. The Generalist digs into the origins and investing philosophies of “the best blitz chess player in the world of venture capital today.”

✋ We’re all chirologists now. On The Hedgehog Review, a professor returning to a masked-up classroom goes down a rabbit hole on “chirology”—the discourse of the hand.

😐 Hold it right there. The New York Times explores the world of botox, and how elective facial muscle paralysis somehow became a symbol of authenticity.

⚰️ Morticians let loose. Mic attends the National Funeral Director Association’s 2021 convention, where “the pandemic’s last responders” dissect a hellish year.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a shortage-free weekend,

—Nicolás Rivero, tech reporter (and a fan of the classic 1970s film Convoy)