Quartzy: the new look edition

Happy Friday!

Happy Friday!

I’m Anne Quito, Quartz’s design and architecture reporter. Today’s dispatch is inspired by my recent trip to France.

I began in Paris, at the glittery Christian Dior retrospective at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. There, among the beaded, Versailles-ready gowns, the exhibition’s centerpiece was a rather plain ensemble: a cream nip-waisted jacket paired with a full, black mid-length skirt. Dior’s so-called “New Look” was more than a fashion moment when it debuted in 1947. It was a manifesto for living.

Dior championed luxury as a humanizing element of daily life. During a time of material scarcity following World War II, the designer established his label and courted controversy with his lavish use of textiles; some even called the New Look’s voluminous skirt “unpatriotic.” In defense, he wrote in the introduction to his debut collection: “In a time as dark as our own, where luxury consists of guns and airplanes, our sense of luxury must be defended at all costs.…I believe that in it there’s something essential. Everything that goes beyond the simple fact of food, clothing and shelter is luxury; the civilization we defend is luxury.”

In an age when we equate luxury with extravagance, Dior’s assertion that it’s essential to civilization may strike some as outlandish. But while luxury can take the form of couture gowns, Louis Vuitton luggage, and Salon champagne, it can also mean taking pleasure in humbler delights. A man from Bordeaux I met on a train described luxury as feeling the warmth of the sun on his face every morning.

What Dior and the French reminded me is that luxury—at whatever scale—is vital. Sometimes, it’s even free.

On this trip, I eschewed a planned itinerary in favor of a flâneur‘s uncharted path. Defined as the mid-way between laziness and activity, the flâneur‘s luxury involves (momentarily) rejecting all calls, meetings, and appointments to seize time for oneself.

Charles Baudelaire says a wanderer’s motive is to “wed the crowd,” and lose oneself. “It’s an immense pleasure to take up residence in multiplicity, in whatever is seething, moving, evanescent and infinite: you’re not at home, but you feel at home everywhere,” he explains in the essay The Painter for Modern Life. “The observer is a prince who, wearing a disguise, takes pleasure everywhere.”

A flâneur‘s single agenda, as Baudelaire suggests, is to be present and open for an unforeseen spectacle.

How to eat breakfast like a flâneur. I have my own twist to luxuriant flânerie. When visiting a new place, I ride my jet lag and rise very early to seek out the most elaborate breakfast in the vicinity. I often find this in a luxury hotel that I’m not staying in—an easy venue for solo travelers not yet acclimated with a new place.

The “elaborate” part is key. No self-serve buffets (though often hard to resist in Asia) or grab-and-go cafés. Sitting down for a meal alone allows one to experience local hospitality and intuit an aspect of their sensibility. A restaurant’s service, after all, is a kind of cultural performance—the experience is both grounding and educational.

A hotel breakfast ceremony usually begins in the same way: As you approach, the faint din of glass and silverware sound like musicians tuning their instruments before a performance. Then, a warm cup of tea or coffee. Maybe a newspaper and a menu soon follow.

As the meal progresses, subtle variations emerge: In London a plate of soft scrambled eggs was presented with great panache under a comically ornate plate dome. In Tokyo, a smiling server offered a small box for my handbag. Afterwards, small bites of fish, slivers of rolled omelette, rice, and pickles appeared in beautiful ceramic vessels. And in Turin, my breakfast theater ended with a sleepy waiter offering an assortment of chocolate hazelnut cakes.

I take no photographs of these solitary breakfasts, but I take it all in. The hour is fleeting and precious—an experience perhaps even more special because it wasn’t documented or shared.

Small indulgences. Reflecting on everyday luxuries this week made me think of my late grand aunt, Emerita. A Sorbonne-trained philosopher, she lived an ascetic life except for two earthly pleasures: French cheese and Swiss chocolate. Ever serious, she hardly smiled except when presented with cheeses and chocolates.

Emerita extolled the virtue of calibrated indulgence. ”To begin with, I should not eat chocolates, and that’s the reason why I’m doubly enjoying it,” she declared the last time we were together. She passed away the day before I left for France.

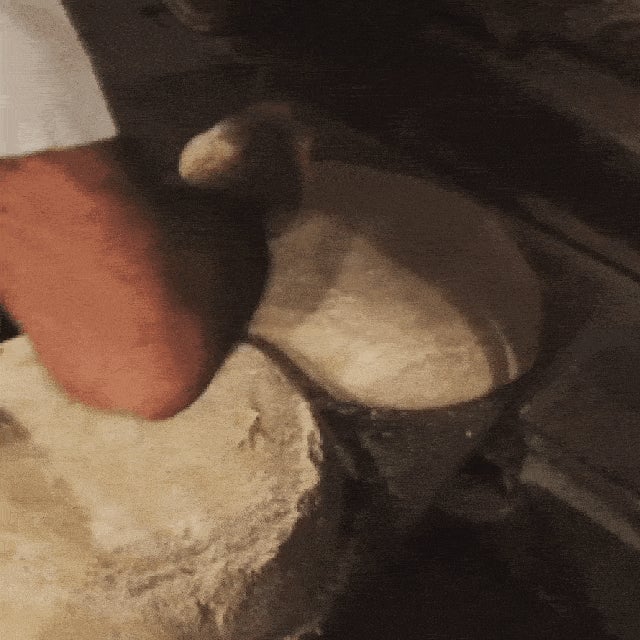

I tried to import this notion of everyday luxury by schlepping a beautiful, 3 lb. hunk of French sourdough back to Brooklyn. My precious cargo was a freshly-baked miche from the superb Parisian bakery, Poilâne. Marked by a calligraphic letter P on the surface, pain Poilâne is tangy and airy, with lots of wonderful holes to catch butter and jam.

But apparently, an enormous hunk of bread raises red flags with airport security. My bag was flagged for extra screening, with agents eyeing me as if I was smuggling a dagger or contraband raw-milk cheese inside the dense orb.

“Is it just bread?” asked the agent at Charles de Gaulle, lightly tapping on the still-warm surface.

Just bread? It wasn’t just bread. It was the bread! Sublime, transcendent, vital bread, sir. The inquisition was but a minor hassle for the weeks of Poilâne toasts, BLT’s, and grilled cheese sandwiches to come. (It freezes well.)

Have a great weekend!

This weekend, I’m eager to see “Faces Places,” a new film co-directed by street artist JR and the grandmother of French new wave cinema, Agnès Varda. Driving a goofy van that looks like a giant camera, the duo scope rural France in search of heroism in ordinary lives. The New York Times called the documentary “powerful, complex and radical,” and I think it looks just delightful. It won the Golden Eye Prize at the Cannes Film Festival this year, and just premiered in the US. Watch the trailer here.