Happy Friday!

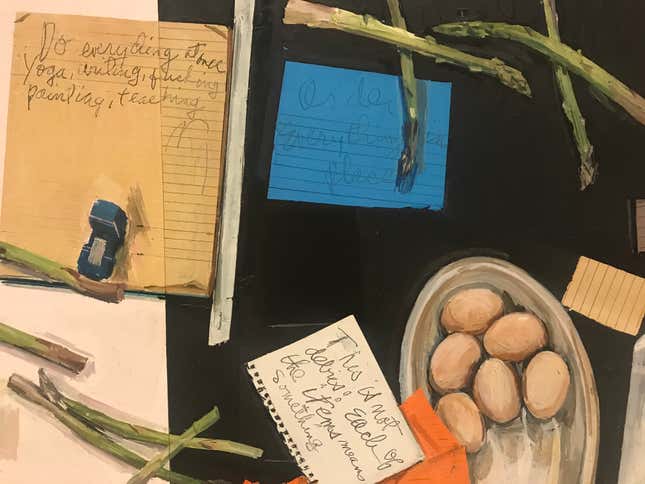

A single table-scape by the painter Manny Farber contains more life than most galleries. He painted surfaces littered with everyday detritus—handwritten notes on slips of paper, punnets of berries, root vegetables piled into colanders, vases of wilting homegrown flowers, rulers, matches, day planners, and half-finished glasses of water—and played with perspective in rich brushstrokes that bring Maira Kalman to mind.

“Do everything at once yoga, writing, fucking, painting, teaching,” reads the cursive script on a slip of lined yellow paper sitting beneath a roll of tape and asparagus spear in one such painting.

“It’s a pretty good spread,” said my friend David on Sunday, facing one of these table-scapes as we worked our way through the new exhibit One Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art at MOCA in Los Angeles.

Farber, who died in 2008, was a film critic and painter who worked in New York during the 1950s and 1960s, before he moved to San Diego, where he taught visual arts and film criticism at the University of California San Diego.

“Termite art” comes from his 1962 essay, published in Film Culture, “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art.” In it, Farber calls for filmmakers and artists to burrow through the landscape of daily life, intensely concentrated on their craft, as opposed to creating mega-masterpieces that are suffocated by their own grandeur.

“What a termite art aims at,” he wrote, is “buglike immersion in a small area without point or aim, and, over all, concentration on nailing down one moment without glamorizing it, but forgetting this accomplishment as soon as it has been passed; the feeling that all is expendable, that it can be chopped up and flung down in a different arrangement without ruin.”

It would be a mistake to consider termite art any less ambitious than masterpiece art. It just concentrates on smaller stuff, as Farber wrote, and will chew through boundaries as it does.

If you’d like to consider the question of white elephant art vs. termite art but can’t make it to MOCA between now and March, you might check out the delightful new documentary The Price of Everything, which is out in select theaters now and will air on HBO Nov. 12.

In it, filmmaker Nathaniel Kahn goes behind the scenes and interviews blue-chip artists, Sotheby’s executives, gallerists, and critics to examine the tension between creativity and commerce. If you love contemporary art—and particularly, painting—it’s worth it just to watch the likes of Marilyn Minter, George Condo, and Jeff Koons’ minions at work.

The white elephant (or silver bunny?) in the room, of course, is Koons, whose gleaming stainless steel statues have commanded upwards of $25 million at auction.

Meanwhile, the documentary’s termite nibbles away in a rickety barn, hand-slapping paint onto a palette behind an improvised curtain of insulation padding. He is Larry Poons, a painter once associated with contemporaries such as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Frank Stella (who calls Poons “Mr. Natural”). He fell off the popular radar when he evolved beyond the geometrical abstractions that made him famous in the 1960s.

As the New York Times’ A.O. Scott points out in his review of the film, it would have been easy to make Koons the villain and Poons the martyr, toiling away in relative obscurity for an artist of his caliber. But that would have been lazy and not quite accurate. After all, Poons is still striving, painting, prepping for his comeback via a solo show at a Manhattan gallery. Had he stayed in the heat of the spotlight, the artist says at one point, he doubts he would be alive today.

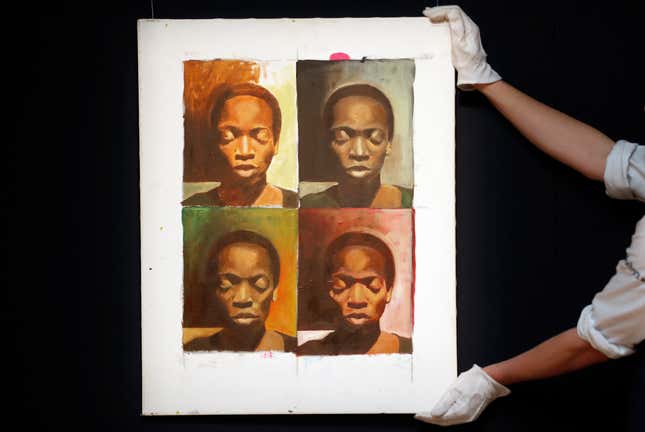

Endurance, after all, is one of the termite’s superpowers. With the Nigerian-born artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby—in her 30s with a new baby, and paintings newly auctioning for over $1 million—Kahn shows a painter aware of how precarious a rapid rise can be. While hefty auction prices don’t necessarily fatten artists’ pockets immediately, they do ratchet up the pressure.

“There’s a temptation to get [paintings] out fast,” Crosby says, in her east LA studio. “But if I speed up the production of the work, it will take away from all that’s behind the scenes that makes the work as rich as it is.”

“It’s not about making a lot of money in the next five years and buying a beautiful house in LA—although that would be good!” she laughs. “But that’s not my driving force.” She wants her work to hang in museums, she says, for future generations. Sure, it might just sit in storage if she falls out of fashion, but then, it could re-emerge. “Someday, maybe in 50 years, maybe in 70, maybe in 150, it could come out. It doesn’t just vanish.”

To me, the real joy in this movie, aside from Poons’ expressive caterpillar eyebrows, was watching painters paint—and fight for the focus and inspiration necessary to maintain that privilege.

Have a great weekend!

[quartzy-signature]

Hey, you. On the topic of termites nibbling at their boundaries, I’ve been writing this newsletter for over two years now. You’ve probably noticed that we’ve recently had some guest contributors, and I’m eager to experiment more myself with these weekly missives. I’d love to know what’s working (and not working) for you, dear reader, so write me back! If you reply to this email, I’ll receive it.