Happy Friday!

I’m Jenny Anderson, a senior reporter at Quartz. I live in London and cover the science of learning, how babies learn and grow, and how we connect to one another—which is what I’m writing about here today.

Five years ago, on a blustery March day, I locked arms with my mother and walked into a church in Maplewood, New Jersey to bury my brother. I remember shivering and worrying: that my dad would slip, my mom would collapse, and that I would botch the eulogy.

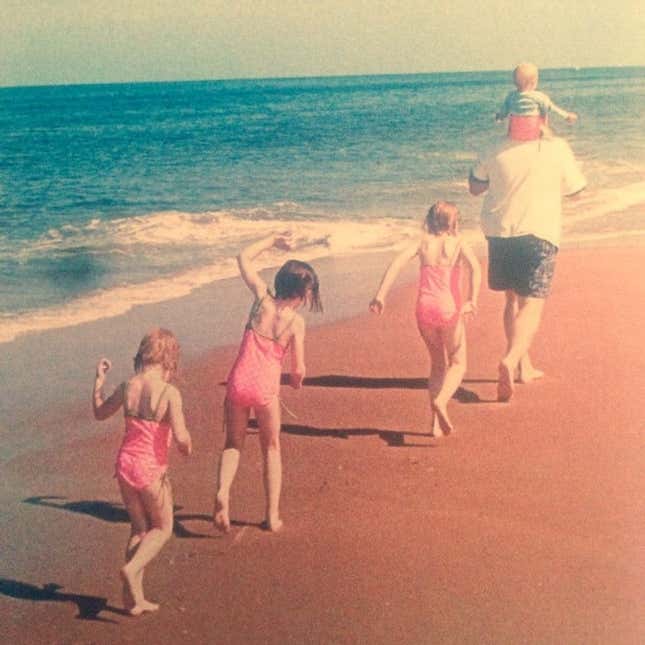

When I stood up on the lectern and saw several hundred people, all of whom seemed to actually know my brother, I was humbled by the life he had created: building his own architecture firm in New York City, raising four girls, belonging to a community that he helped create—by coaching lacrosse, talking to neighbors in the yard and strangers at the grocery store, and attending approximately two million children’s birthday parties.

In seeing his community, I became acutely aware of the feeling that I did not have my own. I had friends and a loving family. But as Annie Dillard wrote, “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.” And I spent my days focused on optimizing myself: endlessly working and improving, on a permanent quest to do as much as possible in the unforgiving confines of 24 hours. It was the only way I knew how to be. Compete. Excel. Win.

I had never considered there might be a cost to a life of high-octane, high-reward competition.

Before Robbie got sick, if you had asked me if community mattered, I would have said yes. But I wouldn’t have thought about it much. Nor would I have spent much time working out what it meant.

But after many nights in emergency rooms and hospitals, of watching my nieces slowly lose their father, I got a glimpse of what community looks like. It was the people who turned up before they were asked, to do things they didn’t have time to do. Neighbors who collected kids from school and came to hospitals. Friends who stayed. Groups who materialized to make lunch for four kids because their parents couldn’t.

This was community. And what I have come to learn, slowly, is that community is about a series of small choices and everyday actions: how to spend a Saturday, what to do when a neighbor falls ill, how to make time when there is none. Community is knowing others and being known; investing in somewhere instead of trying to be everywhere. And communities are built, like Legos, one brick at a time. There’s no hack.

Why community matters. The late John Cacioppo pioneered the field of social neuroscience and dedicated more than two decades to studying loneliness. Loneliness—defined as the discrepancy between a person’s desired and actual social relationships—is everywhere, he found. It does not discriminate by income or class, by ethnicity or gender.

Cacioppo also explained how misunderstood it could be—associated with social isolation, depression, introversion, and poor social skills, when in fact it has more to do with our individual needs. Humans don’t just require the presence of others, he wrote, but rather the presence of others who value them, “whom they can trust, and with whom they can communicate, plan, and work together to survive, prosper.”

These people can, of course, be friends. But mine come from so many chapters of life—high school, grad school, work, Mexico, Colorado, London, New York. They feel more like a constellation than a community. So I had to build one.

Let down the defenses. A key to feeling connected is being there for others, so that they will in turn be there for us. “We need mutual aided protection,” Cacioppo explained to the Guardian.“If you are only receiving aid and protection from others, that doesn’t satisfy this deeper sense of belonging.” This means asking for help, and offering it. (And as we learned from the recent Quartz Obsession on the Ben Franklin Effect, asking for a small favor may even help you gain some trust and approval.)

But when I’m feeling lonely I can also feel defensive. (What’s my problem? Why is everyone else so happy?) That’s totally normal, according to Cacioppo’s research. He found that when we are lonely our brains can turn in on ourselves, causing us to retreat into self-preservation mode and to be on high-alert for social threats.

Calling an old friend or inviting a neighbor to coffee in those moments can be especially hard; it requires being vulnerable at a moment when one feels uniquely unsuited to do that. But that’s precisely why it’s so powerful; it offers the possibility for true connection, and respite from the pain of feeling alone.

Get over yourself. Too often when we are depressed or lonely, we are told to medicate our chemical imbalances or self-improve: do more yoga, be more mindful, eat more paleo, work four days, travel intentionally.

Julia M. Rohrer, a researcher at the Max Plank Institute, studied a large group of Germans who said they were committed to trying to become happier. Some pursued self-improvement goals such as getting a new job or making more money, while others spent more time with friends and family. A year later, she found those who focused on connecting more with others were happier than the self-improvers.

“Our results demonstrate that not all pursuits of happiness are equally successful and corroborate the great importance of social relationships for human well-being,” her team concluded.

Brick-by-brick. Building community demands time, attention, intentionality. When we moved into a new house, I acted as if we would stay forever, although I had no idea how long we would be there.

I slowed down. I introduced myself to my neighbors, joined a book club, and tried church. I became the manager my daughter’s football team (soccer, for the Americans) and started playing tennis with a few local friends (with drinks after, to ease the scald of declining skills).

I used to think that community was as simple as having friends who bring a lasagna when things fall apart and champagne when things go well. But I now think it’s really an insurance policy against life’s cruelty; a kind of immunity against the loss and disappointment and rage that does come. My community will be here for my family if I cannot be. And when I die, my kids will be surrounded by people who know and love them, quirks and all.

In building toward the future, I’ve made the present so much richer. Less me, more others. A problem shared is a problem halved, my kids were taught at school. Communities do that too.

Have a great weekend!

Have an imperfect dinner party. Dinner parties are a great way to connect. My key lesson: don’t worry so much about the presentation (perfect dishes, Instagram-ready house) and focus more on the process (togetherness, booze, edible food). Think less Nigella Lawson and Marie Kondo, more pot-luck with clothes-piles stashed in closets. For this sort of occasion, Quartz’s culture editor Indrani Sen slow-roasts a pork shoulder and calls it a taco party. And who doesn’t love a taco party?