Quartzy: the nice at work edition

Happy Friday!

Happy Friday!

I’m Sarah Todd, a senior reporter for Quartz At Work.

A while back, some professional acquaintances and I were talking about the phrase “resting bitch face”—a controversial term meant to describe women whose default facial expressions make them appear angry or cold. “You don’t have that,” someone told me. “You look more like a mark.”

I wasn’t surprised to hear that strangers might see me and think, Now there’s a good target for my next scam. As a generally sunny person, I’m accustomed to the fact that people often perceive a cheerful, smiling face as a sign of weakness.

Still, it’s telling that the opposite of “resting bitch face” is an “easy to manipulate” one. It’s a clear example of the warmth-competency tradeoff (pdf), a research-backed phenomenon in which women who act friendly and warm are viewed as less competent, while women who develop a reputation as high performers are often seen as aggressive or difficult. This means that women face a maddening double bind in the workplace: Is it better to seem nice but dumb, or smart but unlikable?

Why “nice” is a bad word at work. Powerful politicians like Hillary Clinton and Elizabeth Warren are two high-profile examples of the ease with which our culture deems successful women to be cold and calculating. Less frequently discussed, but just as insidious, is the bias against nice women at work.

“For women who conform in certain ways to the expectation that women are friendly and warm, the consequence for them is that their skills can be overlooked,” says Marianne Cooper, a sociologist at Stanford University’s VMware Women’s Leadership Innovation Lab and the lead researcher for Sheryl Sandberg’s bestseller Lean In.

Consider one 2018 study (pdf) of 81,000 performance evaluations of military leaders. Men were most frequently praised for being “analytical” and “competent,” while women got points for being “compassionate” and “enthusiastic.”

As the study’s authors explain, the focus on women’s people skills means that they may be more likely to get passed over when it comes to decisions about hiring and promotions. “The term analytical is task-oriented, speaking to an individual’s ability to reason, to interpret, to strategize, and lending support to the objectives or mission of the business,” they write in the Harvard Business Review. “Compassion is relationship-oriented, contributing to a positive work environment and culture, but perhaps of less value to accomplishing the work at hand.”

Blame the patriarchy. So why do so many workplaces assume that a woman who’s generous to her coworkers couldn’t possibly also be great at crunching numbers and strategic planning?

In a patriarchal society, niceness, compassion, and kindness—all stereotypically feminine traits—are bound to be culturally undervalued. The result is that many workplaces instead place a premium on stereotypically male qualities like dominance, resulting in “masculinity contest cultures,” a term coined by Cooper and her fellow sociologists Peter Glick and Jennifer Berdahl.

Writing in the Harvard Business Review, they explain: “This kind of culture endorses winner-take-all competition, where winners demonstrate stereotypically masculine traits such as emotional toughness, physical stamina, and ruthlessness. It produces organizational dysfunction, as employees become hyper competitive to win.”

Masculinity contest cultures make everyone unhappy, leading to higher rates of burnout, turnover, illness, and depression. And it’s ultimately terrible for business. Glick, Cooper, and Berdahl point to Uber as an illustration of how sexual harassment and other misconduct can thrive in workplaces that prize aggression and competition over listening and cooperation.

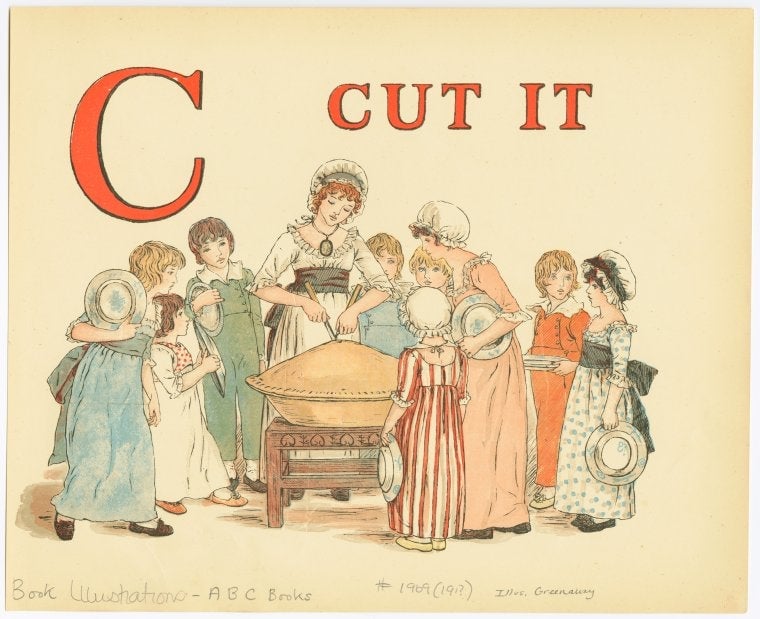

Bake together, stay together. Thankfully, there are ways to introduce cultural norms and routines at work that encourage people to prize kindness, compassion, and even fun.

One of my favorite traditions at Quartz’s New York office—and something that would never fly in a masculinity contest culture—is our Great British Bake Off pop-up club, born from one coworker’s fierce devotion to the cultural institution of her homeland. As a new season of the baking competition airs, we gather weekly to dissect the latest episode over baked goods. Participants are each assigned a contestant; when “their” contestant gets eliminated, it’s their turn to bring in a homemade treat. (The Quartz group, like the the show, is mixed-gender.)

The meet-ups share some DNA with fika, the Swedish tradition of taking twice-daily coffee breaks with colleagues, which has been linked to reduced stress and higher productivity. It’s undeniably relaxing to step outside of the hustle and bustle to talk about a topic entirely unrelated to work, and to learn more about one another based on our opinions on tarragon or whether it’s fair to expect the Bake Off contestants to know a choux pastry recipe by heart.

Tasting one another’s delicious concoctions—and talking about the inspiration behind each person’s recipe of choice—has undoubtedly brought us closer together, too. Some of the group’s most recent offerings have included swirled sesame muffins, apple cake, a citrus-y semolina loaf, the Argentinian tart pasta frola (recipe in Spanish), and a Halloween-appropriate red velvet cake with a “blood” topping.

Valuing kindness. There’s no simple fix to warmth-competency stereotypes. But part of the solution lies in dismantling rigid binary notions of masculinity versus femininity, logic versus emotion. If we can all evolve to see empathy and compassion as qualities that are equally valuable in men, women, and people of all genders, bosses will be a lot less likely to dismiss the intelligence of women who treat others well.

That would be good news for everyone, since workplace cultures that treat talent and kindness as qualities that go hand in hand help employees to stay in touch with—or even deepen—our humanity. In the words of Quartz’s global news editor John Mancini, whose last day at our publication is today, the feeling you get at a place where people sincerely care about one another goes beyond dedication. It approaches something like love.

Speaking of The Great British Bake Off. If you’re looking for a case study in playing nicely with others, there’s no better source than the GBBO season now streaming on Netflix. While the show is designed as a competition, the contestants are famous for what Quartz’s Annaliese Griffin calls “heart-melting civility,” jumping in to help one another when someone has fallen behind and offering comfort, hugs, and advice when a bake goes wrong. It’s no coincidence that the contestants who create this kind of environment have little interest in upholding traditional gender norms. In one recent episode, a female host, Sandi, wandered over to three male bakers gathered by the refrigerator. “Welcome to the least laddy lad’s club,” one man said proudly. “We’re discussing the setting temperature of gelatin.”