Dear readers,

Welcome to the first issue of Quartz’s space business newsletter, where I’ll consider the economic possibilities of the extra-terrestrial sphere. Think of this less as a link roundup and more as an ongoing conversation. Please forward it to your friends and enemies, and let me know how I can make it more useful.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Let’s start with a provocation: American astronauts aren’t landing on the Moon in 2024.

Since March, when US vice president Mike Pence announced the new plan—take a very notional 2028 Moon landing and knock it out four years earlier—there was a delightful frisson that something might happen. The Moon is in vogue, the Moon has ice, the Europeans want to go, billionaires want to go, the Chinese are going (therefore the Americans have to go), Donald Trump loves space, and July even marks the 50th anniversary of the dang Apollo Moon landing.

Sic transit gloria spatii: It turns out NASA didn’t actually have a plan for Pence’s deadline. When they put one together, lawmakers in the House mostly denied a $1.6 billion down payment for the mission, named Artemis to reflect the agency’s intention of putting the first woman on the Moon. Mark Sirangelo, an executive hired to lead the Artemis mission, left NASA after a 44-day tenure. NASA won’t say how much Artemis will cost for fear of inducing sticker shock, but the best rumors peg the total at $8 billion—annually!

An accelerated moon landing is likely to be subsumed in Washington’s broader fights over domestic and defense spending, unless powerful Republican senators like Richard Shelby (who has yet to weigh in) and Jerry Moran (who tweeted that he will fund a moon program, but not when) get involved.

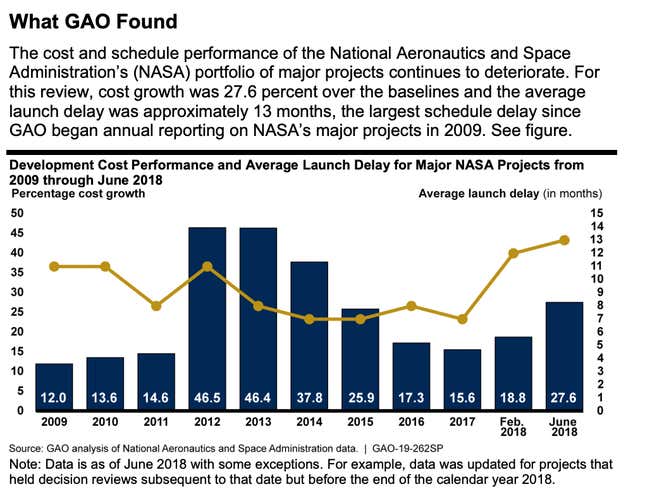

But here, a chart is worth 1,000 words (or tweets). This one, from a recent audit (pdf) of NASA’s major projects, found them delayed by over a year on average. Even if Congress does end up putting a down payment on Artemis, the smart bet would be on a missed deadline.

“What’s sad is to see this mad political dash by NASA to reach a goal that is untenable,” a longtime space policy hand says. “If all it took to do something like go to the Moon in 2024 were speeches and rhetoric from political figures in the White House and NASA, don’t you think this would have been done before?”

There have already been semi-obituaries for the semi-program. Kenneth Chang’s “Can Trump Put NASA Astronauts on the Moon by 2024? It’s Unlikely,” is top-notch. Eric Berger’s “NASA’s full Artemis plan revealed: 37 launches and a lunar outpost,” gets to the point in a section outlining the “Three Miracles” Artemis would need to succeed.

Then again, who cares? The Trump campaign can use the 2024 date in re-election ads regardless of its feasibility, and space insiders are reluctant to criticize Artemis because they believe going to the Moon is a good idea, and trying to pull the date forward can’t hurt. Meanwhile, the average American isn’t as interested in Moon missions as anyone in at NASA HQ, doesn’t remember Apollo so fondly, and (in a few sad-but-true cases I’ve encountered) thinks the US already has a Moon base. There’s unlikely to be any public outcry if NASA misses its deadline, or if the US government’s credibility on deep-space exploration continues to suffer.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery Interlude: Neil Armstrong celebrates the birthday of this newsletter—or, rather, he celebrates his 39th birthday in quarantine, weeks after returning from the Moon in 1969. Per NASA, “Armstrong’s cake was a ‘standard two-layer, plain vanilla,’ and featured a full array of 39 candles. Eighteen of the persons quarantined with Armstrong assembled for a champagne toast and a rendition of “Happy Birthday.”

🌘 🌘 🌘

SPACE DEBRIS

(This, dear readers, is where we’ll share the most interesting nuggets of news and opinion from the past week.)

Mea culpa: Last week, I wrote about Amazon’s new satellite ground-station service, part of the big-compute behemoth’s move to plug satellites directly into its cloud network. It’s a potentially important development, but Mark Harris took the time to check the FCC filings and found the service only has legal approval to work with one of its eight currently announced partners. That’s a reflection of Amazon getting ahead of itself, but also of the regulatory thicket that is satellite operation.

The link in our stars: There has been a good bit of hand-wringing over SpaceX’s Starlink satellites and their initial appearance from Earth as lights marching across the sky. But why the surprise? Discussion of the huge numbers of low-flying satellites planned for launch by SpaceX, OneWeb, LeoSat, and Amazon have been a staple of space conferences and regulatory forums for years. True, there are very real concerns about space debris and Earth-based astronomy, but if past worries about satellites visible to the naked eye are any indication, this too shall pass with a little coordination. Musk and Co. say they will work to make future Starlink satellites harder to see.

Moonwalla: If all goes according to plan, the first American Moon lander of the 21st century will be designed in India. That’s because NASA is asking for companies to handle the job of sending scientific sensors to the Moon, and one of those companies turned to TeamIndus for its lander design. TeamIndus is one of the many children of the Google Lunar XPrize, which managed the trick of seeding a half-dozen companies without actually giving out its grand prize.

Goodbye, Stratolaunch: The late Paul Allen should be remembered for a lot of good things, but his decision to build the world’s largest aircraft to launch rockets still baffles me. It may have likewise baffled the inheritors of the project, which Reuters reports is set to be shuttered (I haven’t been able to confirm this directly). Barring theories about top-secret military shenanigans, this modern Spruce Goose wasn’t going to launch satellites more capably or efficiently than the many new competitors in the rocket space.

Chinese rockets take to the sea: The China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT) flew two satellites from an oceangoing platform today, the first time China has launched rockets from the ocean. The South China Morning Post celebrated “the first nation to fully own and operate a floating sea launch platform,” suggesting that the Sea Launch project, a former joint venture of US, Ukrainian, and Russian firms, failed because of political conflict. In fact, Sea Launch went dormant because of launch failures, high costs, and the fact that rockets don’t much love corrosion from the salt-sea air. Let’s hope the Chinese have better luck.

your pal,

Tim

Hope your week is out of this world. Please send any lunar schemes, UFO reports, tips and informed opinions to tim@qz.com.