Fill ‘er up

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extra-terrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Gas stations in space, rocketry with Chinese characteristics, and why the heck isn’t NASA looking out for deadly asteroids?

🌘 🌘 🌘

A big idea driving people back to the moon is the possibility of harvesting the water ice there and converting it into hydrogen and oxygen—two common types of rocket propellant.

Why does that matter? Rockets taking off from Earth are mostly propellant—typically about 90% of their mass is some kind of carbon-based fuel and an oxidizer that allows that fuel to combust in the vacuum of space. (This is why rocket engineers often use the word “propellants” instead of “fuel”). Most of it is expended just getting to orbit, which leaves little left to get around in space, and little room for weighty cargoes.

But, if you could launch a spacecraft and re-fuel it with propellants from the moon instead of flying them up from the ground, the cost of getting around in space could fall dramatically. This could enable NASA to bring more stuff to Mars more quickly, for example, making deep space missions feasible. It could also make prosaic launches far cheaper as well. Tasks that seem simple to people unfamiliar with orbital mechanics—like fixing or moving a broken satellite—are actually quite hard, but in-space refueling could make them doable.

United Launch Alliance, the Lockheed Martin/Boeing joint venture, has kicked around the idea of refuelable space tugs, while Elon Musk’s SpaceX has in-space refueling as a key point in its plans to head for Mars. There’s just one problem: Nobody has the technology yet to transfer volatile, super-chilled liquid chemicals from one highly pressurized system to another in microgravity.

This week, NASA announced that it would partner with SpaceX to work on this very problem, part of a broad roll out of new projects where private firms will contribute to NASA’s proposed 2024 return to the moon. These collaborations don’t involve money changing hands, but private companies getting access to NASA data, expertise and sometimes facilities to push their own investments forward.

Other projects on NASA’s new list of public-private partnerships include developing new materials for lighter rockets, powerful new fuel and solar cells, and even the tools necessary to grow plants in space.

It’s worth noting that in-space refueling has plenty of critics in the space establishment; in a useful history of the concept, Ars Technica’s Eric Berger notes that advocates of NASA’s Space Launch System rocket killed plans to further study the technology in 2011 because they saw it as competing with their own project. With the SLS still on the ground nine years later, anyone looking for innovation now has to turn to the private sector.

🌘 🌘 🌘

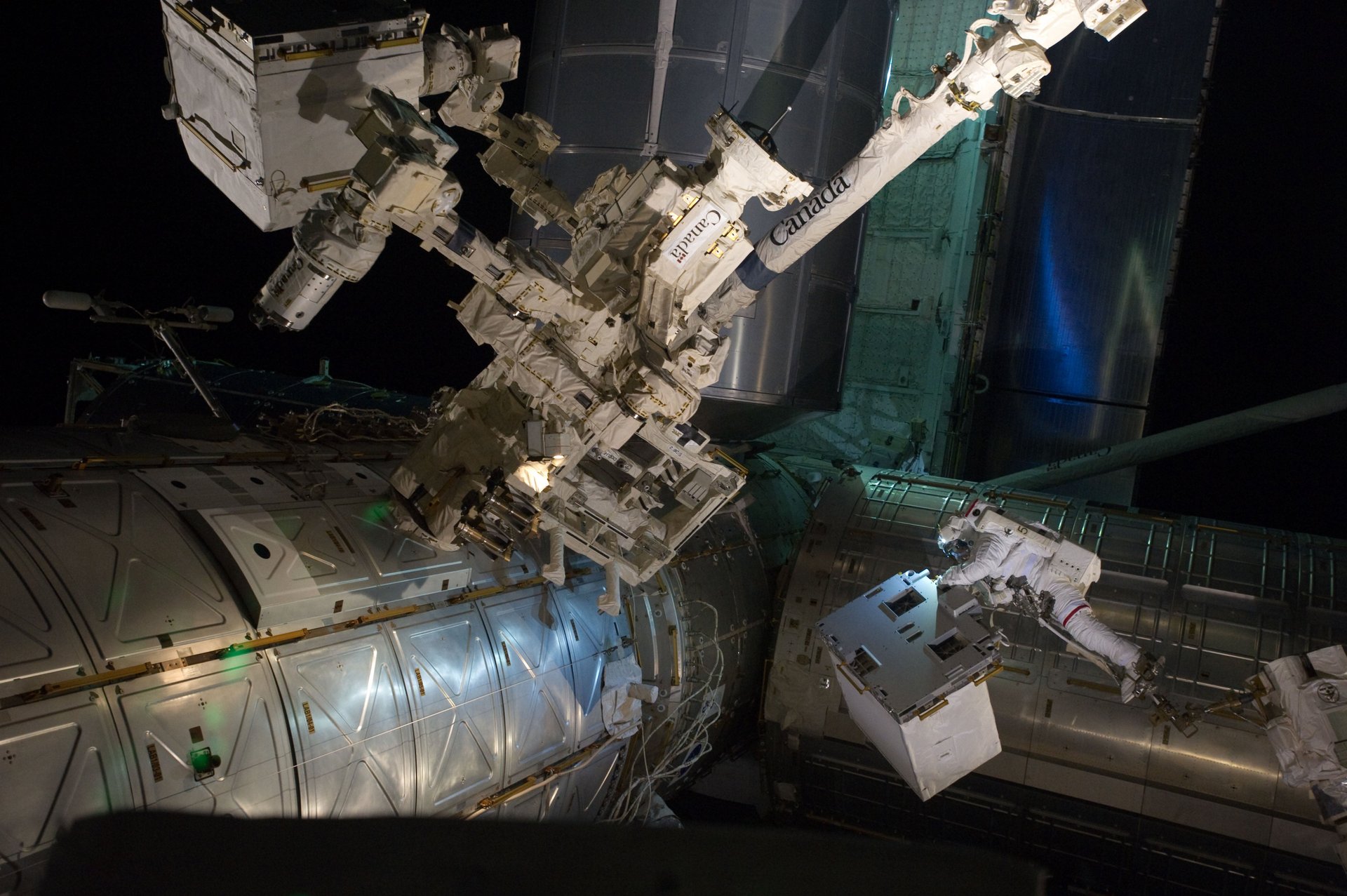

Imagery Interlude: NASA’s most recent experiments with in-space refueling began in 2011, when the Robotic Refueling Mission was launched on the final space shuttle mission to the International Space Station. Here, astronaut Mike Fossum prepares to install the platform on the outside of the station, where it was used to practice robotic top-offs.

The RRM is still on the station today and being used for technology demonstrations.

🚀 🚀 🚀

An asteroid just missed the Earth. Astronomers were dismayed to see an asteroid estimated to be 130 meters across pass within 45,000 miles of the Earth (far closer than the moon) without any warning. Reminder: NASA has declined to pay for an asteroid hunting space telescope that the National Academy of Sciences says is the best way to spot potentially deadly asteroids. It’s part of a funding stand-off between the space agency and Congress, but it’s not clear who is going to budge when it comes to working on what the public says is NASA’s most important mission. A spokesperson for Arizona senator Kristen Sinema, the senior Democrat on the subcommittee overseeing NASA, said she supports the mission and will push her colleagues to fund it.

Red Musk. China’s push to develop a “private” space industry continues apace. We learned last year that China began yearning for its own SpaceX competitor following the launch of the Falcon Heavy. Earlier this month the country rolled out rules to incentivize its private rocket companies. This week China’s military even slapped some grid fins on an orbital launcher. Also this week, a Chinese company borrowed the cultural iconography of Elon Musk’s crew. For its first launch, the Chinese company iSpace carried with it the model of an SUV, a reference to the Falcon Heavy carrying a Tesla into space on its maiden launch. But is it also a sneaky way to get a government subsidy? The carmaker sponsoring the launch, Changan Oushang, is state-owned, and said that it was acting in response to the government’s call to support the space industry.

Radar raise. The Japanese company Synspective raised $100 million to launch a constellation of synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellites, mostly from major Japanese industrial firms. Now it will compete with startups like Capella Space and ICEYE. According to the financial data firm Preqin, new investment in space companies had been trending slightly lower this year than last, but between Synspective and the curious Virgin Galactic reverse-merger IPO, we’re still seeing cash flow to space firms.

Come sail away with me. A small satellite launched by the Planetary Society deployed a thin metallic sail and caught a gust of solar wind that raised its orbit above the Earth by more than a mile. The demonstration that spacecraft can move with the solar wind fulfills decades of work that began with Planetary Society founder Carl Sagan, and will allow for cheaper exploration missions. One such project, planned to begin next year, will send a tiny spacecraft solar sailing toward the asteroid belt.

Robotic bodyguards. The US has been warily eyeing (and publicly decrying) Russian experiments with spacecraft that can fly up to satellites. Russia says they are just working on fixing broken satellites, but like most space technology, it can also be used to break working satellites. Former RAND analyst Brian Chow says Russia using these satellites as weapons is inevitable, which seems a bit much, but he offers two plans to do something about it: Set up an international norm for keeping your distance from other spacecraft, and prepare to position robotic bodyguards around US satellites. What could go wrong?

your pal,

Tim

This was issue nine of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your favorite rocket fuels, disguised subsidies, tips and informed opinions to [email protected].