War Time

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extra-terrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Death from above, the satellite surge and, please, let’s just get commercial crew flying.

🌘 🌘 🌘

The latest war—well, the latest iteration of America’s endless war in the Middle East—began, as it tends to do, in space.

On Jan. 3, US military satellites directed an unmanned aerial vehicle to take off from a US base in Qatar. The Reaper drone flew toward Iraq, and when it was in range, a US Air Force service member in Nevada ordered it to fire two missiles, also guided by satellite. Cars carrying the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani and the leader of a Shi’ite militia exploded.

This was not, frankly, an unusual story in recent years, except for the political importance of the individuals targeted. The ability of America’s space-augmented fighting force to affect conventional destruction has been amply demonstrated in ongoing conflicts, brushing aside the Taliban, the Iraqi Army, and ISIS, respectively. It also draws a harsh contrast with the US inability to create any kind of political stability in the aftermath of these conflicts.

What’s new, though, is that the US advantage may be slipping away. To be clear, few doubt that the United States could defeat Iran in a conventional war. But now the United States is not the only country that can use modern technology to drop explosives on a target thousands of miles away.

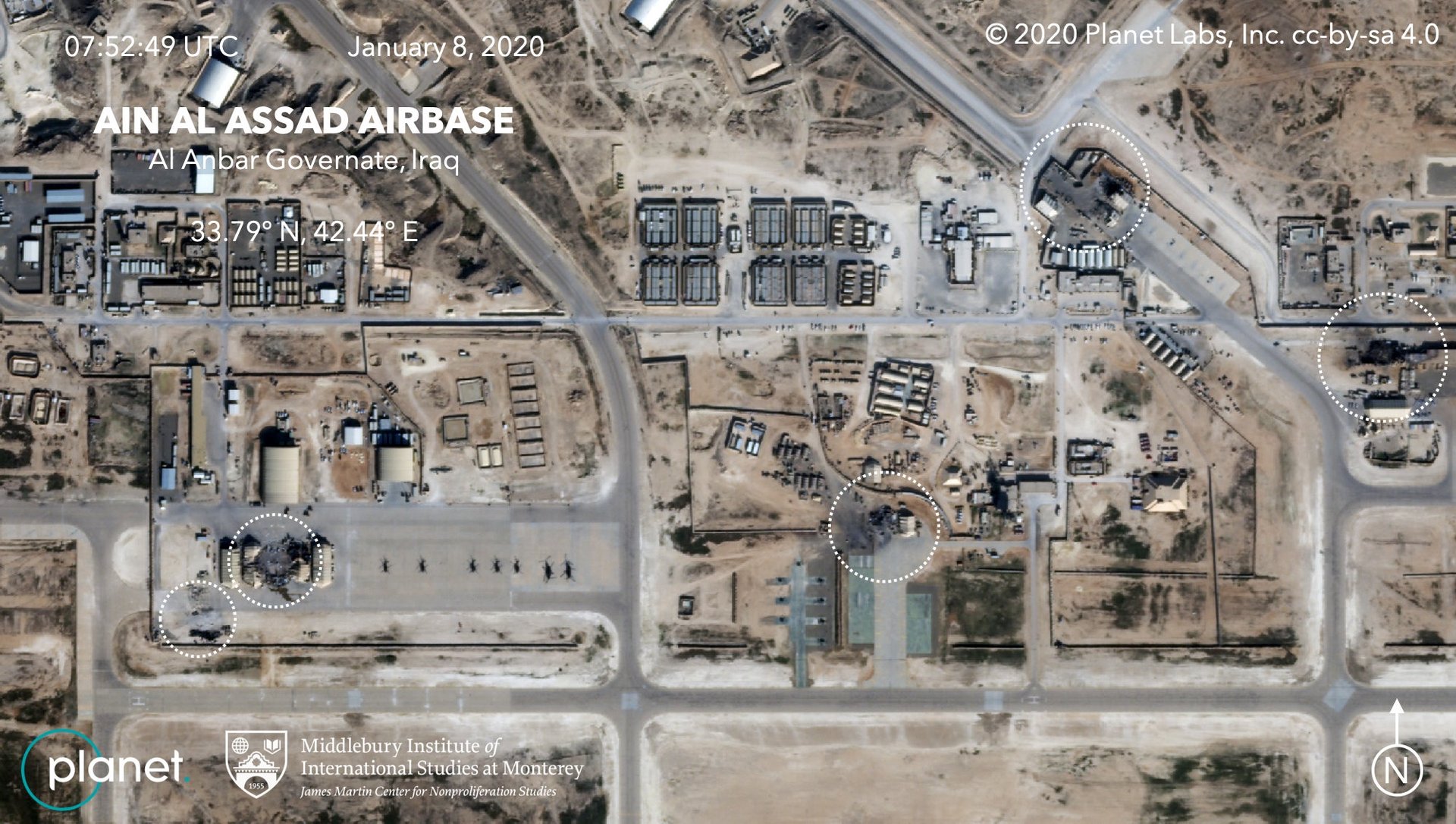

Consider during the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, Saddam Hussein’s regime launched 23 missiles at US troops; nine were shot down by US missile interceptors, and the rest missed. On Jan. 7, Iran launched a dozen missiles, and most if not all appear to have hit their targets, at least according to after-action imagery released by the satellite firm Planet and analyzed by the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. It’s worth noting that a private company and independent analysts provided more information about the attacks to the US public—and more quickly—than the government itself.

The strike can be seen as a reprise of a September attack on Saudi Arabian oil facilities, where oil storage tanks were precisely targeted by Iranian drone and cruise missiles. Fabian Hinz, a Middlebury researcher, told the Washington Post that this new accuracy represents “a quantum change.” Now these missiles aren’t just terror weapons but capable of taking out specific targets.

Equally worrying from the American point of view is that its anti-missile defenses are not very effective. The Patriot missile defense system isn’t very effective against maneuverable, low-flying drones and cruise missiles, and its record against ballistic missiles is questionable at best. For example, it failed to stop a comparatively unsophisticated 2017 missile attack on Riyadh.

The same trends that are making space cheaper for billionaires are doing the same for countries great and small. Big US rivals like Russia and China are expanding their missile arsenals past US capabilities, and countries like North Korea and Iran see similar investments as a way to elide the work of building an army, navy and air force capable of taking on the United States.

Ironically, markets have reacted to the news by betting on missile-makers like Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and Raytheon, whose stocks all popped in the new year. US spending to catch up with its rivals is a likely forecast as long as US president Donald Trump remains in office.

Today, there is hope that Iran and the United States are satisfied with their belligerence and won’t feel the need to continue to escalate, though tensions between the two nations are unlikely to subside. US commanders, though, will rightly note that they can no longer count on enemy missiles missing, and that may constrain American options in the future.

🚨 Read this 🚨

If you, like me, are a person of a certain age (33), your parents are also reaching a certain age. In the US alone, 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 every day. My colleague Lila MacLellan recently faced the modern rite of passage of helping her parents make the transition into assisted living. In this week’s field guide, she shares what she learned about how seniors live today—including, god help us, the forthcoming era of “geriatric cool.”

🚀 🚀 🚀

SPACE DEBRIS

MOAR SATS. The first US rocket launch of 2020 goes to SpaceX, which tossed 60 more Starlink internet satellites into orbit on Jan. 6. Get ready for more: Elon Musk’s team wants to launch 22 Starlink missions alone from Cape Canaveral this year. Meanwhile, Arianespace, the European launch champion, says it will also fly 22 missions this year, including 11 launches for OneWeb, which is building its own network of internet-broadcasting satellites. And that’s just two companies! Suffice it to say that we’re in for a satellite surge in 2020.

Abort. Test. Abort Test! The end of the year brought a disappointing finish for the commercial crew program after Boeing’s Starliner failed to reach the International Space Station on its uncrewed test flight. NASA and Boeing are still analyzing exactly what went wrong and right, but the failed test clearly wasn’t what the aerospace giant needed. Dennis Muilenberg didn’t step down as CEO because of the anomaly, but it didn’t exactly help.

Reading between the lines of the public statements, it seems that the US space agency would like more than anything to give the go-ahead to Boeing to proceed with its crewed flight test, since another uncrewed test would be expensive and time-consuming. Still, having spoken to NASA officials who white-knuckled it through the first visits of the SpaceX Dragon and Northrop Grumman Cygnus spacecraft to the $150 billion ISS, I have to ask you, readers—would any other aerospace company get to pass GO and collect $200?

Much may depend on SpaceX’s final test, the inflight abort now scheduled for Jan. 18. If the company’s Crew Dragon spacecraft shows it can successfully separate from its rocket and carry astronauts to safety in an emergency, that will help take pressure off the whole program. NASA engineers will still have to spend months checking all the paperwork before they give either SpaceX or Boeing a shot at flying astronauts.

Reverse-financing lunar lander. The travails of NASA’s Artemis lunar return program will continue in 2020, as the space agency tries to use less than half of the money it requested to get started on building a lunar lander. NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine now says the agency may ask bidders like Blue Origin’s consortium, Boeing or SpaceX to invest more of their money to make up the difference. And more change may be on the way, with Doug Loverro, the new head of NASA’s human spaceflight work, suggesting the mission architecture may change yet again before the administration’s next budget request this spring.

Virgin Galactic’s new spaceplane. Me, you and everybody else are all waiting to see when Virgin Galactic actually flies some paying passengers in 2020. In the meantime, the company says it has built its second spaceplane to the point where it can stand on its own wheels as an integrated object, and constructed over 50% of the parts it needs for the third vehicle. When VG began its transition to a public company last year, I was curious if they could meet their stated goal of building a new spaceplane every year, a must to reach the flight cadence necessary for profitability. At least by that metric, they’re on track. One other indicator to watch: The company told investors it expects to fly 66 passengers to the edge of space by the end of 2020.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 29 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your estimates for how many Starlink satellites will be in orbit by 2021, your assessment of US missile defenses, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected]. If you enjoy this newsletter, take 50% off becoming a Quartz member.