Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Gas stations in space, watch out for China’s falling rocket, and Falcon Heavy flies again.

🚀 🚀 🚀

It’s been a busy year for the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve: In the face of surging oil prices, the government sold hundreds of millions of barrels of crude stored deep in salt caverns along the Gulf Coast. The move took some of the bite out of US energy inflation in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The SPR was created in 1975 in response to that decade’s oil crisis, but the idea of a publicly backed energy reserve had been around since the 1940s. If your entire economy is dependent on oil, it’s a good idea to make sure you always have some around.

What about the space economy—what is it dependent on? Billionaire enthusiasts, sure, but those are difficult to store for on-demand use. In space, the hardest thing to find is propellant for a vehicle, because so much of it is used to simply break free of Earth’s gravity. That, in turn, limits what governments and businesses can do beyond the closest orbits to Earth.

Earlier this year, United Launch Alliance CEO Tory Bruno and his colleagues released a white paper outlining how the US government should invest about $22 billion in creating a Strategic Propellant Reserve in space. It’s not a new idea, but the team of rocket scientists and economists has put out a sophisticated model of the business plan to do it as a public-private partnership between the government and industry.

The scheme lines up with a number of trends in space: NASA’s Artemis program is already planning to explore the water ice in the Moon’s south pole with an eye toward exploiting it, and private investors are increasingly eager to plunge into the hypothetical lunar economy. ULA rival SpaceX is planning to refuel its Starship vehicle in space in order to use it as a lunar lander.

The paper envisions setting up an industrial ice mine on the Moon, then storing water in convenient locations around the solar system. Then, as needed, the relatively simple process of electrolysis would split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen, a common propellant mixture for rockets.

A depot on the Moon’s surface could refuel lunar landers and support habitats. Another in a special orbit around the Moon and the Earth would be ideal to fuel future Mars-bound spacecraft or hypothetical US Space Force vehicles. Water could be stored in Mars orbit to enable easier returns of future visitors. It could even be trucked back to low-Earth orbit to fuel satellites, though the math may not quite pencil out for that.

It’s an expansive vision, one that would require (at least) 10 years of work and proving out some new technologies, among them efficiently refueling without the benefit of gravity. Coming from ULA, known for its reliable launch history more than its dynamic technology development, it’s maybe even a bit of a stretch.

Bruno tells Quartz that he doesn’t envision ULA developing a novel ice mine or operating the depots. Instead, this infrastructure would allow his company to transition from being a to space company to a through space company—one that does more than place satellites in orbit, instead taking payloads to multiple destinations in the solar system. You could imagine a comparison with the auto industry asking the government to provide infrastructure, but propellant depots in space would be more like the national highway system than the SPR itself.

The analysis emerged from a question Bruno was asked as part of a group advising the National Space Council—what’s one thing the US government could do to have a tremendous impact on economic growth in space? Such a plan would also require some kind of new organization—it’s not really a NASA civil science mission, although NASA has this expertise, nor is it an explicitly military project. It might, Bruno muses, be ideal for collaboration between the Department of Commerce and the space agency.

If the government were ever to take up this plan (a very big if given the cost of Artemis itself and the likelihood of general budget cuts in the years ahead) it would be an inflection point in the space economy, pointing the way towards business models that are even more far-fetched, like space solar power and asteroid mining. “There is tremendous wealth between here and cislunar space, and just beyond,” Bruno says. For now, he hopes to spur more serious discussion and analysis ahead of 2023 robotic NASA mission that will attempt to offer the first ground truth on the lunar south pole.

This kind of infrastructure would also freak out US rivals like China and Russia; despite American insistence that it simply wants free and open activity in space, they would see an effort like this as the US expanding its military capabilities.

And they wouldn’t be wrong. A major customer of the depots would be the US Space Force, which the white paper expects to use spacecraft that “move around cislunar high ground for a variety of classified reasons.” When I asked Bruno if he was referring to actual classified plans for US spacecraft or just forecasting them, he declined to answer.

🌕🌖🌗

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

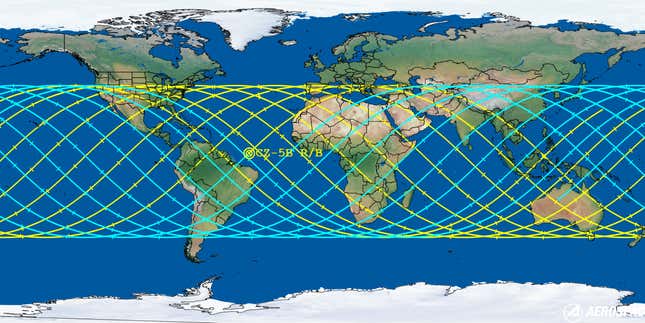

Last week, China launched a Long March 5B rocket to add a new module to its space station. But the rocket’s 22 metric ton core stage is now falling back to Earth in an uncontrolled tumble; two previous launches of the rocket dropped debris in populated areas. The Aerospace Corporation, a US government-funded research lab, says there is a six in 10 trillion chance that the debris hits someone—but that’s too high in a world where we have the technology to safely guide space debris like this to a safe demise in the ocean. Here’s the current forecast of where reentry may occur, likely on Nov. 5.

🔊🔊🔊

Your productivity is not your worth. Have you tried slowing down a little at work? Your coworkers might thank you. Get some useful tips, from the slightly rebellious to the full-blown renegade, on the season finale of Work reconsidered.

🎧 Listen to this week’s episode of Work Reconsidered on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

🛰🛰🛰

SPACE DEBRIS

Falcon Heavy flies again. The most powerful operational rocket in the world flew for the first time in three years this week, to launch a pair of secret satellites for the US Space Force. It may be made obsolete when SpaceX gets Starship flying, but Eric Berger assesses its legacy more positively.

Rocket Lab to grab a booster. The company plans to launch one of its Electron rockets on Nov. 4 to deliver a Swedish research satellite to orbit, and then catch the falling booster with a helicopter. The first attempt in April failed when the pilot released the booster for safety reasons, but if successful, the company could begin cutting costs by using refurbished launch vehicles.

Terran Orbital pivots to Lockheed. The satellite manufacturer, which went public through a SPAC last year, raised $100 million from Lockheed Martin as part of a pivot that will see the company abandon plans to build a factory in Florida and launch its own satellite constellation, and instead manufacture key components for other customers.

China’s secret space stuff. A reusable spaceplane launched by China and thought to be similar to the US X-37B has released an object in orbit, according to the US Space Force. The object is likely another small spacecraft, but its purpose could be anything from monitoring the spaceplane itself to testing new sensor or maneuvering technology.

Tales from the SkyBox. Here’s an interesting interview with Dan Berkenstock, the founding CEO of SkyBox, a satellite company that was acquired by Google for $500 million in 2014, helping kick off venture investment in space business. (SkyBox was ultimately bought under the name Terra Bella by Planet in 2017.)

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 157 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your solar system-scale infrastructure plans, forecasts for the Long March core stage impact, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].