Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: The joys of logging on, Blue Origin’s turbopump works, and other forms of space internet.

🚀 🚀 🚀

SpaceX’s novel broadband network in space has begun to demonstrate its chops for military pilots and firefighters. Now individual consumers will get their first crack at testing the service. According to leaks from testers, the price is $99 a month, plus a $499 on-boarding fee, presumably covering the cost of the satellite antennae users will need.

Billed as a “better than nothing Beta,” users are warned that their connections may occasionally fail. It’s hard not to see this as a last-minute attempt to fulfill Musk’s promise that service would begin this year. Still, if fulfills its promise of “50Mb/s to 150Mb/s and latency from 20ms to 40ms,” it would provide faster data transfers, albeit at higher latency, than your humble correspondent’s Comcast connection in Oakland, California.

Starlink would also cost more than my internet—but not by very much, since I pay extra for faster service in a world where my wife and I now work from home. Moreover, people who live in denser areas are not the real target for these services—rural internet access is quite a bit more expensive. An existing satellite internet provider, Hughes Net, quoted a price of $139 a month for 25 Mb/s speeds and a 50 gigabyte data cap in rural Washington, one state where SpaceX’s trial is underway.

What this is, then, is a competitive solution for edge cases in the US consumer broadband market. It’s not getting the world’s poor online, but we already knew that: Satellite entrepreneurs market their services to regulators and the public as an access-increasing solution, but for the moment their main customers are militaries, oil rigs, cruise ships, and anyone else willing to pay a premium in a remote location. If SpaceX ever takes Starlink public, it will be fun to see how the revenue breaks out, and we’ll certainly be scrutinizing its application for US subsidies to provide rural internet access.

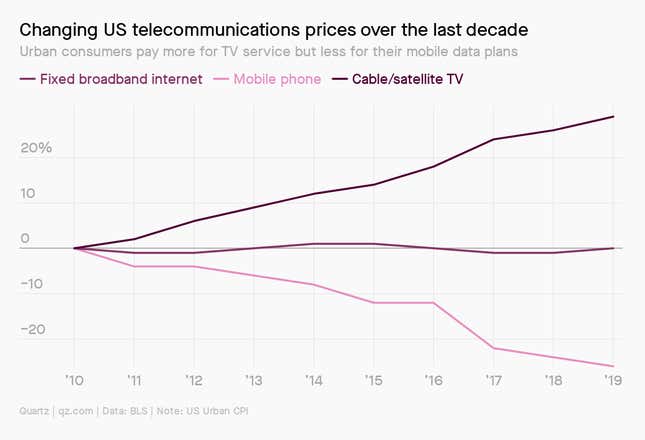

And yet there is hope that these systems will increase access in the long term, through competition. Consider recent trends in the ways urban Americans pay for data, taking note that these indices include improvements in quality as well as changes in price:

In the last decade, the price of fixed broadband internet has stayed roughly the same, reflecting improving service as well as rising prices—consider that according to the OECD, in 2014, Americans paid about $50 a month for 15 Mb/s speeds; in 2020, they pay about $60 for speeds of 25 Mb/s. (Also worth noting: Americans pay more than any other developed country for their broadband, versus an OECD average of about $37 a month.)

The cost of mobile data has fallen considerably, which also makes sense considering the differences between what you could do with a phone in 2010 and what you can do today. Most noticeably, cable and satellite TV costs have continued to rise—but the product hasn’t changed that much.

Economists suspect the differences come from the amount of competition in these markets. Mobile phone data plans are offered by multiple providers in dense areas, but reliance on expensive physical infrastructure for cable internet and most broadband means that, in 2018, 68 million Americans only had one option for those services. Many, like me, have to choose between just two; in Oakland, unfettered broadband means either Comcast or AT&T.

As more and more of the information we want converges on the internet, this is going to get more complicated. The FCC has ruled that cable TV providers can raise prices because internet TV services like Hulu count as competition. Meanwhile, it’s not clear that individuals actually need that much more quality from their internet service providers. One thing we have seen: Cable companies have invested more in infrastructure upgrades where they receive competition from pure ISPs.

There are a lot of unanswered questions about Starlink’s capacity and quality—how many customers can it add, at how much density, and where? But if it—and other satellite networks—can compete effectively on quality with terrestrial operators, something not quite possible now, price competition could follow.

P.S. Are you a Starlink beta tester? Holler at me!

🌘 🌘 🌘

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

The internet only came to the International Space Station for real in 2010; prior to that, astronauts would relay their communications to the world through NASA channels. (This independent access has led to some complications.) The first use of this internet was, naturally, a tweet from astronaut TJ Creamer. This picture of Creamer at an ISS console does not depict him sending the historic missive, but I feel it captures the thrill of logging on nonetheless:

👀 Read this 👀

In the abstract, the internet is a zone of digital freedom. In practice, the messy physicality of the internet—all those cables and server farms and transceivers—give states plenty of control.

But what if the internet took to the stars? If the hardware behind all the bits was in orbit, it might be harder for governments to restrict its use. That is one of the most interesting potential consequences of next-generation space internet: That a US company might link prosecuted Uighurs in China to their global diaspora, or a Chinese satellite company might beam unrestricted TikToks into American homes.

Could satellite internet break the splinternet? Find out more in our field guide.

🛰🛰🛰

SPACE DEBRIS

Man the pumps! Two widely-anticipated new rockets, ULA’s Vulcan and Blue Origin’s New Glenn, are expected to make their debut flights next year. A key holdup has been the engine built by Blue Origin, called BE-4, that will power both of these vehicles, but now the problem is reportedly solved. The problem was found in its turbopump, perhaps the most complex part of any rocket engine. It remains to be seen how much the delay knocks either company off course.

Crew News. The first operational flight of the SpaceX Crew Dragon is now scheduled for Nov. 14, with the company and NASA performing several critical engineering reviews in the weeks ahead. Yesterday, officials explained that SpaceX will switch two of the engines on the Falcon 9 rocket after a previous launch was aborted because a leftover substance used in manufacturing blocked a key valve. Top SpaceX engineer Hans Koenigsmann says the company is carefully inspecting critical engines on upcoming flights and adapting its manufacturing protocols to ensure the problem doesn’t happen again.

Speed of light protocols. The internet on earth works through a digital protocol called TCP/IP, developed in part by a pioneering computer scientist named Vint Cerf. These days, Cerf is looking at the challenges of managing a much larger communications network—the methods behind TCP/IP don’t work with the challenges of interplanetary communications, and now he and his collaborators are developing a more effective approach.

Speaking of interplanetary internet. SpaceX threw a little easter egg into its Starlink terms of service, which note that “for Services provided on Mars, or in transit to Mars…the parties recognize Mars as a free planet and that no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities.” Some folks are mad about this! It should go without saying: As long as SpaceX is a US corporation, and its employees and customers are US residents, it’s going to be hard to contractually escape US law—the sovereign citizen movement has tried this, to little effect.

Perhaps in a future where Elon Musk has retired on Mars, we can look forward to a US plaintiff winning a judgment from SpaceX under US law, Musk refusing to acknowledge it, and the plaintiff happily seizing its share of whatever revenue SpaceX earns on earth. Then Musk and the Martians declare independence—sure hope the colony is self-sustaining by then!

Fun Facts. Enjoy our capsule history of GPS.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 71 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send baroque interplanetary legal scenarios, your bets on when Vulcan and New Glenn take flight, tips, and informed opinions to tim@qz.com.