Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: A departing NASA administrator, Virgin’s orbit, and Elon’s oil rigs.

🚀 🚀 🚀

“People need to understand that this is a political job,” former NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine told Quartz last week.

The outgoing head of the world’s largest space agency under president Donald Trump never got a chance to forget that reality. His confirmation hearings focused on controversies from his time as a bomb-throwing conservative lawmaker. His final day on the job was spent arguing for the existence of a bipartisan consensus on space exploration.

Bridenstine is aware that many NASA administrators have seen their most ambitious proposals canceled after they leave office, and is capable of listing failed moonshots.

“Think back to the late 1990s with the space exploration initiative, to the moon and on to Mars—it got canceled because the legwork was never done to build the consensus,” he says. “To build a sustainable program, you have eliminate divisions, you have to build consensus, and you have to get the budgets to match the rhetoric.”

Bridenstine’s signature initiative is Artemis, a program intended to return astronauts to the moon, in particular the first woman. The target date of 2024 was seen as unlikely from the get-go. While Bridenstine is right that lawmakers of all stripes back a moon landing, it never won the financial support required to make that timing realistic.

That’s in part because many saw the 2024 target as inextricably tied to Trump’s political ambitions. Throughout, Bridenstine argued that the hasty pace was required to buy down a different kind of political risk—that Congress, impatient with stagnant programs, would simply cancel Artemis if it came with a more realistic deadline.

That thesis will be tested under the new Biden administration. Bridenstine’s final public appearance as administrator was during a press conference to explain an anomalous test of the huge Boeing SLS rocket designed to return astronauts to the moon. The aborted demonstration means additional delay, and perhaps will provide an excuse for policymakers to alter the program.

Still, Congress has invested tens of billions of dollars in the SLS rocket and the Orion space capsule. It has also spent hundreds of millions preparing other elements of the program, from robotic reconnoissance missions to a lunar way station to vehicles and spacesuits to protect astronauts on the surface of the moon.

Bridenstine is rightly proud that NASA’s budget has grown significantly during his time as administrator, but it’s worth noting that a booming economy and a Republican president tend to ease such spending. Now, with a different party in the White House, we will see if Bridenstine has managed to erase the divisions he saw when he came to NASA.

“There was this challenge where Republicans were in favor of the moon and Democrats were in favor of going to Mars,” Bridenstine said. “It created this division that kept us from going anywhere. Republicans were for human exploration and Democrats were for the science mission directorate.”

He is advising Biden’s transition team that “the best thing that any leader of this agency can do is find out wherever there are divisions and eliminate them.” One example is NASA’s plan to hire private companies to send robots to the moon. Traditionally, such a program would be part of NASA’s human exploration programs, but under Bridenstine, it is led by the science directorate.

“It’s not human exploration or science, it’s both, and they both can do more when they work together,” he says. “The narrative where everything is a zero-sum game…that narrative is what I thought was important to break down.”

Like many leaders in a sector with decade-long projects, Bridenstine’s biggest moments came shepherding existing programs to their finish, most notably the return of human spaceflight to the US with SpaceX’s crew Dragon capsule, the OSIRIS-Rex asteroid sample return mission, and the launch of the Mars 2020 exploration mission. The administrator was generous in crediting his predecessors, in contrast with the White House’s insistence that it had single-handedly revitalized NASA.

Another major aspect of Bridenstine’s legacy is in international law. As a member of Congress, he pushed for US property rights in space. As NASA administrator, he authorized missions to purchase lunar samples from private companies, creating a precedent for such exchanges. And he led an effort to develop norms for safe activity on the moon, called the Artemis Accords.

One of his main concerns as he leaves is how to manage the environmental consequences of growing activity in space, which might be seen as ironic given early worries that his climate change skepticism would continue as the leader of a scientific agency. (Congress ignored the Trump administration’s increasingly pro forma requests to cancel climate change research.)

“I’m worried that given the amount of debris and aggressive activity happening in space, that it might not be sustainable,” Bridenstine says. “In other words, our children and grandchildren won’t be able to explore space the way we would like to be able to explore space. We need to bring in as many nations as possible. That’s a critical piece of American soft power.”

Of course, there’s one key nation in space that the US doesn’t deal with directly, and that’s China. I asked if the US should drop its legal prohibition on cooperation with China’s civil space activities.

“If Congress and the administration were to make a determination that NASA should be a tool of diplomacy when we engage with China, I think NASA would be a great tool of diplomacy,” he said, diplomatically. “The question is, what are the behaviors that we want to see changed from China, and could NASA engaging with China result in those behavior modifications? If the answer to that is yes, I think NASA would stand ready to engage in a meaningful way.”

Now, Bridenstine will return to Oklahoma to spend time with his family after eight years in Washington. He says he’s not sure if he will return to aerospace in the future, but that he has high hopes that Artemis will keep moving.

“What I’m hoping that we’ve done now, differently than those other [canceled] programs, we’ve got the consensus,” he says. “I would encourage the next NASA administrator go even further.”

🌘 🌘 🌘

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

This image of Jason Parrish, a NASA technician helping to transport an Orion space capsule between facilities at Kennedy Space Center, captures my 2021 mood.

👀 Read this 👀

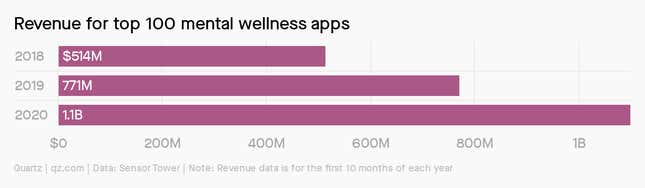

It’s been a big year for being stressed out—and that’s a business.

“The thing that really changed this year is that mental health started to become an everyday conversation,” says Headspace CEO CeCe Morken. The fact that so many people were experiencing grief, fear, and isolation at the same time meant that “some of the stigma around mental health started to drop away,” she says.

Read more about the opportunities this sea change in mental health offers businesses, and everyone else, in this week’s Quartz field guide.

🛰🛰🛰

SPACE DEBRIS

Space Politics II. Veteran space journalist Jeff Foust has written an important column pointing out the ugly overlap between lawmakers who supported efforts to toss out the votes of American citizens last week and those who advocate for space exploration. Senator Ted Cruz, Rep. Brian Babin, and Rep. Mo Brooks are all boosters of the space economy, but also willing spreaders of disinformation. “The danger is if the space community reverts to political expediency, willing to work with any member who shows an interest in space,” Foust writes. “No issue, including space, is that important.”

Virgin: Orbit ✅. Over the weekend, Richard Branson’s company Virgin Orbit completed its first successful launch of eleven satellites into orbit. The company uses a modified 747 to fly its rocket to high altitude before sending its spacecraft on an orbital trajectory. The debut mission suggests that more competition is coming to the launch market and soon small-satellite operators will have another flexible option to deploy their spacecraft.

Back in the lab. Speaking of small launch vehicles, Rocket Lab completed its first launch of 2021—and the payload is an interesting one. It looks like the spacecraft was built by a German company but is intended to stake a claim on satellite spectrum that will be used in some kind of joint Sino-Deutsch internet-of-things network. Say that five times fast.

Reverse Armageddon. Rather than send roughnecks into space, SpaceX instead plans to land future reusable rockets on offshore oil derricks like two the company purchased from a bankrupt driller earlier this year. The company’s next-generation Starship rocket and its even larger booster are unlikely to find sufficient safe landing space at existing spaceports, so the company is looking to floating platforms.

Boeing okays astronaut software. The troubled aerospace giant says the software for its Starliner spacecraft has been approved after the company found significant problems in the code during a 2019 demonstration mission. Now, the vehicle is headed for integrated testing, including a full mission simulation that was skipped last time, before a new demo flight to the International Space Station expected in March.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 81 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send gossip and rumors about Biden administration appointees, thoughts on the SpaceX Raptor engine, tips, and informed opinions to tim@qz.com.