A Boeing spacecraft could have been destroyed by flawed onboard software if engineers had not reprogrammed it mid-flight, NASA officials said.

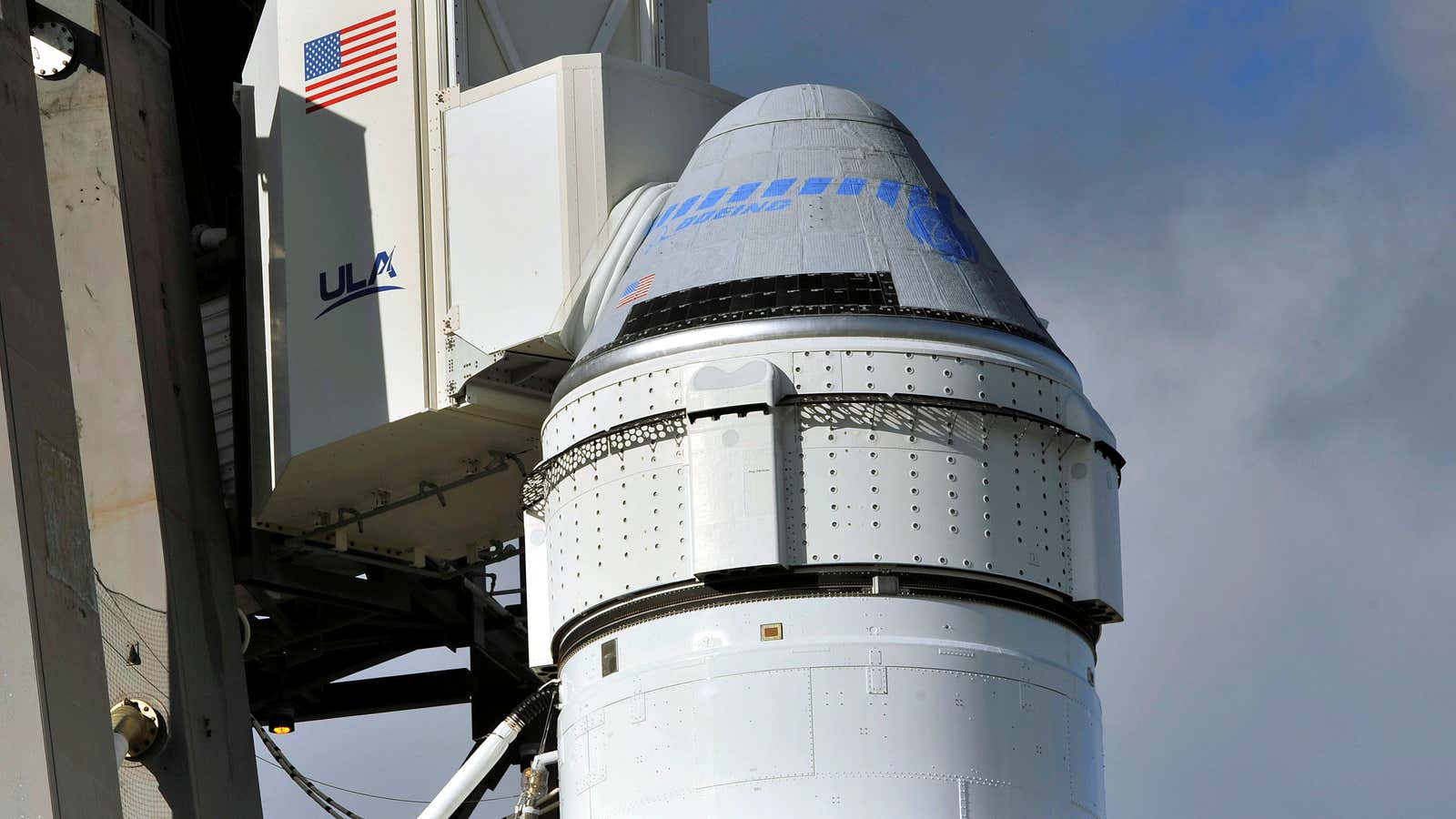

The Boeing Starliner performed an uncrewed test flight in December to prepare for its work ferrying US astronauts to the International Space Station. Starliner reached orbit, but it failed to rendezvous with the space station because its internal clock was off by 11 hours, which led it to miss the key moment to fire its engines.

This week, a NASA safety panel revealed a second software error that could have led to erroneous thruster firings “with the potential for a catastrophic spacecraft failure,” a member of the panel said. Boeing also had difficulty maintaining a communication link between the spacecraft in orbit and ground control, which made operating the autonomous vehicle more difficult.

The anomalies point towards broader problems with Boeing’s approach to designing and testing the vehicle.

“Breakdowns in the design and code phase inserted the original defects,” the US space agency said in a statement. “Additionally, breakdowns in the test and verification phase failed to identify the defects preflight despite their detectability…there were numerous instances where the Boeing software quality processes either should have or could have uncovered the defects.”

“It’s not just the specific issues that we discovered in this flight…the real problem is that we had numerous process escapes in the design, development, test cycle for software for Starliner,” Doug Loverro, the NASA official in charge of human spaceflight, said, using the engineering term for errors that should have been caught.

An Independent Review Team made up of NASA and Boeing staffers who didn’t work on the vehicle are still studying data from the test flight and expect to release a definitive report by March.

The test flight was a milestone in NASA’s commercial crew program, which has hired Boeing and SpaceX to build and operate spacecraft to carry astronauts to the International Space Station. SpaceX recently completed the bulk of its development work and could fly astronauts in a crewed flight test as soon as April. Boeing’s timeline remains uncertain.

Code Red

While the December launch of the Boeing Starliner onboard a ULA Atlas V rocket went swimmingly, engineers realized there was trouble shortly after it separated from the rocket and failed to fire its engines.

At the same time, ground controllers were unable to communicate with the vehicle for several minutes due to problems with its communications link. While the root cause of that failure has not yet been identified, interference from mobile phone towers could be the culprit.

As Boeing and NASA engineers worked to figure out what went wrong in the vehicle’s million-plus lines of code, they came across the second error, in the code controlling how the Starliner capsule separates from its “service module,” a collection of equipment discarded before re-entry. The bad code could have caused the capsule to collide with the service module, possibly destroying it or damaging its heat shield, which would make returning to Earth a suicide mission.

“Nothing good can come from those two spacecraft bumping,” Jim Chilton, a Boeing senior vice president, told reporters.

Boeing’s engineers were able to pull an all-nighter and update the code at about 5 am the next day, just hours before the Starliner performed its separation maneuver. The vehicle was able to successfully re-enter the atmosphere and fly safely back to Earth.

Reviewed anew

Boeing said last week it would take a $410 million charge to its earnings due to the test failure, which could include the cost of repeating the demonstration flight. NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine said that the agency had not yet decided if a second uncrewed flight will be necessary.

The space agency did say it would reverse a previous decision and launch a broad organizational safety review of Boeing. In 2018, the space agency said it would perform “invasive” safety reviews on both contractors. But only SpaceX completed a full safety survey, while NASA only interviewed select Boeing officials.

Now NASA says it will perform “individual employee interviews with a sampling from a cross section of personnel, including senior managers, mid-level management and supervision, and engineers and technicians at multiple sites.”

The decision was made because of the test flight anomaly and what it revealed about the company’s processes, but Loverro also referenced “press reports we’ve seen from other parts of Boeing,” likely referring to the software issues that led to the grounding of the company’s 737 Max airliners.

“It looks as if there could possibly be process issues at Boeing, and we want to understand what the culture is at Boeing that may have led to that,” he said.