Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Trading spacecraft, another layer of SPACkle, and an FAA apologia.

🚀 🚀 🚀

Space businesses, no matter how large, often find themselves hunting for opportunity amidst the gyrations of national space powers.

This isn’t new, as the tale of the US investors who briefly purchased the Mir space station from the Russian government in 1999 can attest. The dawning of what might have been a new commercial space age was torpedoed, per then-MirCorp CEO Jeffrey Manber, by fears that the enterprise would upset negotiations to develop the International Space Station, and bureaucratic jealousy on the part of NASA.

Manber didn’t give up—he now leads Nanoracks, a company that pioneered private-sector partnerships with NASA on the ISS. It recently installed the first commercially designed and owned airlock on the orbital habitat and sold a significant stake to Voyager Space Holdings, the space-focused private equity firm.

And commercial intrigue with an international bent has hardly disappeared—consider the latest news about getting astronauts to the ISS.

Though the US regained its long dormant ability to transport people to the station, thanks to the successful debut of SpaceX’s crew Dragon in 2020, NASA wants to continue flying some US astronauts on Russian rockets, and vice versa, to ensure mixed-nationality crews are on station all the time.

The path to such an exchange goes through the offices of Houston, Texas’ Axiom Space. The firm, founded by former NASA executive Michael Suffredini in 2016, raised $130 million last month for its business flying tourists to the space station and, it hopes, eventually deploying its own orbital platform.

Yesterday, NASA said Axiom would give the space agency a seat on a Russian Soyuz rocket heading to the ISS this April, in exchange for a seat on a future commercial crew vehicle, either the Dragon or the delayed Boeing Starliner, in 2023.

This may be a smart arbitrage for Axiom: If the Soyuz seat cost less than a seat on a future commercial crew mission, Axiom made a profit—and turned a ride on an older Russian rocket into a seat on a modern American design it can then offer to its customers.

If the Soyuz seat was sold at the rates NASA last paid ($90.3 million), then compared to the estimated cost of a seat on a Crew Dragon ($60 million), Axiom just took a $30 million loss as a favor to the US space agency. But if Axiom paid less (Roscosmos sold rides on Soyuz for as low as $21 million in the early 2000s) then they effectively made money on the deal.

It might actually be cheaper for NASA, too—with national pride at stake, Russia would likely demand a higher payment from the US government than it would from a discreet private start-up. When the US was dependent on Roscomos to visit the ISS, the cost per seat soared. Now that the US will fly most of its astronauts itself, the cash-strapped Russian space program is likely to offer Soyuz seats more cheaply.

The company declined to say how much it paid for the Soyuz flight, but said in a statement that “Axiom is always seeking new opportunities to provide access to the Station to non-traditional users,” noting that the astronaut who will join the 2023 flight will represent a national space agency and must be approved by the ISS crew panel.

This isn’t the only business opportunity that Russia is providing to space entrepreneurs. Russia and China announced plans this week to build a research outpost on or near the moon. This would be a rival to the Artemis missions being developed by the US and its international partners, including Canada, Europe, and Japan. The US had hoped to extend the kind of cooperation seen on the ISS and requested that Russia build an airlock for the Lunar Gateway, a planned space station orbiting the moon.

Now, that plan seems moot, and the Gateway—assuming it gets off the ground—will need an airlock. That may be an opportunity for Nanoracks, Axiom, or a number of other firms looking to earn a profit building space hardware for the US government.

🌘 🌘 🌘

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

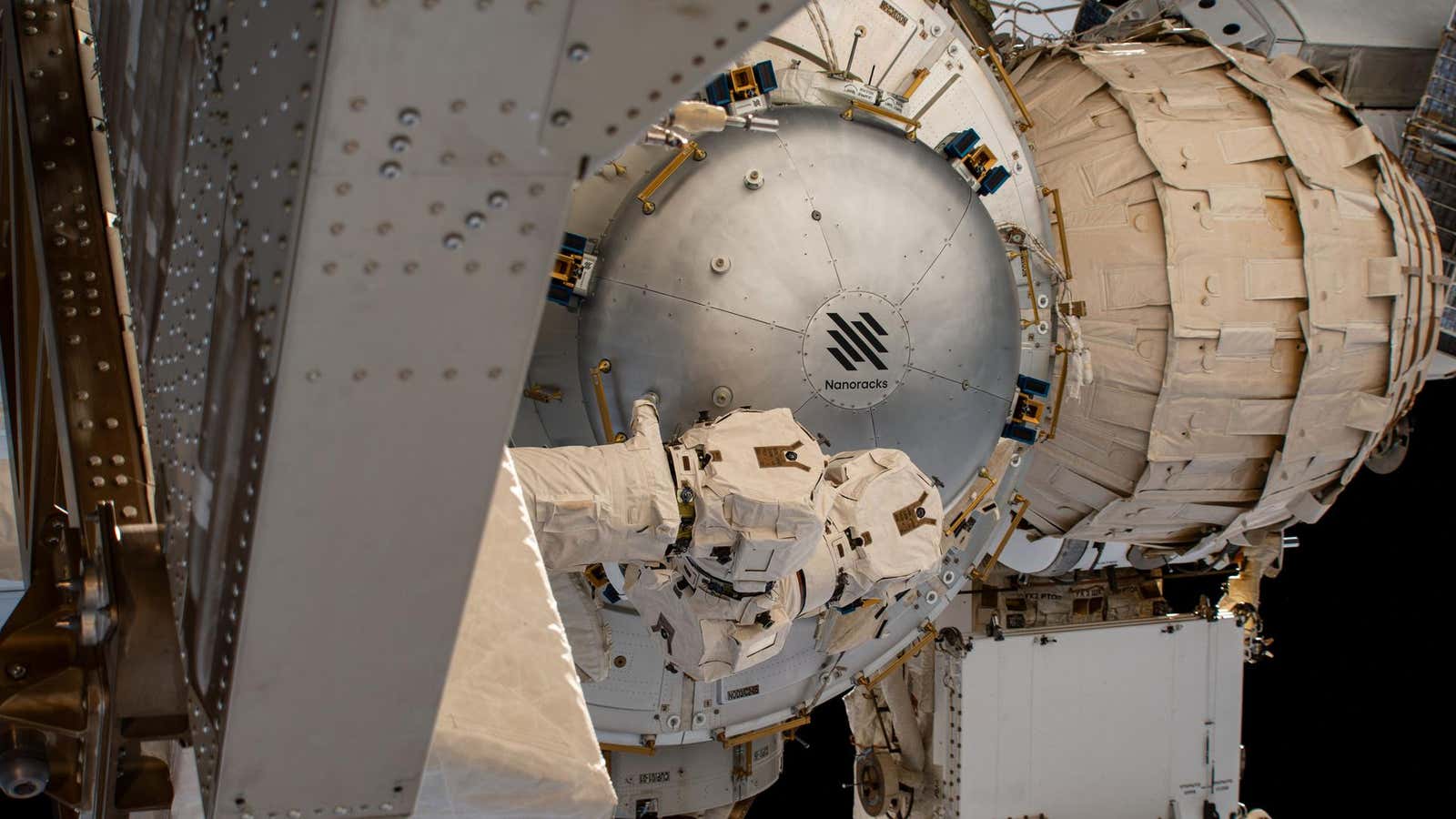

Wondering what the first privately owned airlock on the ISS looks like? Well, like this:

However, I’d recommend watching this video of the airlock’s installation, ideally with some Strauss playing.

👀 Read this 👀

Astronauts have been doing telehealth since NASA attached electrodes to Alan Shepard, but the pandemic has made this approach to healthcare increasingly ubiquitous. Will it remain after we’re all vaccinated?

There are a number of barriers, including the cost of services, issues with insurance reimbursement, and lack of connectivity. But more substantially, patients, as well as the medical community, worry about the level of care that could be administered remotely rather than in person. Though some of these issues have been temporarily resolved, those fixes need to be made permanent in order for telehealth to be a regular part of medical practice in the future.

Read more about how telehealth could become the future of medicine.

🛰🛰🛰

SPACE DEBRIS

SPACS SPACS SPACS. There are seven (!) new space companies going public through mergers with special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), despite the fact we haven’t seen a traditional IPO from the sector. I spoke with engineers, entrepreneurs, and investors to write this deep dive about how the space sector kicked off the current surge in SPACS, and how it could accelerate—or knock off course—efforts to develop mature space businesses.

Exiting Virgin Galactic. It’s not just Chamath Palihapitiya—George Whitesides, the former NASA chief of staff who served as Virgin Galactic’s CEO for a decade before stepping down to a new role after it became a publicly-traded company in 2020, has departed the firm. He’ll remain an advisor, but a new management team still faces a host of challenges meeting the company’s promises to its investors.

Space Force buys some rides. The results of the Pentagon’s decision to tap United Launch Alliance and SpaceX as the Space Force’s rocket makers of choice is paying off this week, with the announcement of two multi-million dollar contracts for each firm.

Is SpaceX cannibalizing its launch customer base? In a filing with the Federal Communications Commission, SpaceX sought permission to use its Starlink satellite network to communicate with ships, planes, and large trucks. That’s not a surprise, since virtually every company offering satellite internet winds up working with customers in the “mobility” market, which is both growing and established. But it may prove a challenge when it comes to SpaceX’s primary satellite-launching business. While building the first low-flying internet network wasn’t a direct challenge to existing satellite operators, going after this market puts them in more direct competition with players like Inmarsat, SES, and Intelsat.

The FAA is doing its best. Elon Musk loves to complain about regulators like the Federal Aviation Administration, which licenses rocket launches, but the truth is often more prosaic. As former Air Force space executive Wayne Eleazar explains, the reason that the FAA delayed a Starship test in early February was not due to bureaucratic slowdowns or anger at SpaceX’s proclivity for blowing up test articles, but because the company had broken a promise not to launch under certain weather conditions in a previous test.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 87 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send ideas on how to improve the space bureaucracy, SPAC gossip, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].