Planetary motion

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: The motion of the Planet, inside the bouncy castle of death, and Momentus vs. the SEC.

🚀 🚀 🚀

The most important news in space business aren’t Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos’ suborbital joy rides. It’s the decision by Planet, the satellite data company, to go public after being bought by a special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC), DMY Technology Group.

Planet is the most mature space company to come to market—it had more than $114 million in revenue last year, which is more than comparable new space businesses that went public through SPACs: Virgin Galactic, a suborbital tourism company, earned $238,000; Spire, another satellite imaging firm, earned $29 million; and Rocket Lab, the launch vehicle maker, earned about $35 million.

It’s also doing the most to mainstream space business, paying careful attention to customers outside of the aerospace sector. It’s been two years since the company began reframing itself as a “data” company, not a satellite operator, concerned that the public was too focused on its achievement of launching hundreds of low-cost PlanetScope satellites that capture images of the earth’s entire landmass every day. The company also operates larger satellites for higher-resolution imagery.

“That’s the back-end,” CEO Will Marshall told Quartz. “People don’t buy [our] satellites…we are providing information. Our financials and business really looks like a data and software business. People are very surprised to see our gross margins. For example, last year gross margins for the Planetscope business were about 62%, which includes the depreciation and amortization costs of the PlanetScope satellites. Most satellite companies have negative growth margins, excluding the cost of the satellites!”

Marshall co-founded Planet in 2010 with Robbie Schingler, the company’s chief strategy officer, and Chris Boshuizen, now a partner at venture firm DCVC. All three worked at NASA and saw a chance to leverage advances in small satellites in the private sector. But a technology is not a business model, and the firm has had to figure out how to make its data useful not just to organizations that already use satellite information, but also those that don’t.

That’s why it’s interesting that less than a quarter of the company’s current customers are defense and intelligence agencies; the biggest buyers of its data are agricultural firms. One recent hire is the company’s president, Kevin Weill, who helped turn Twitter’s firehose of data into saleable insights to advertisers. Marshall sees his company as something like a Bloomberg terminal, but for data about the earth, not the financial markets—and with the same attractive subscription-based business model.

Bloomberg terminal users might agree: One key angle for Planet’s arrival on the public markets is the rise of ESG investing, short for “Environmental, Social and Governance” rules that investors want to see companies adopt. Mega-asset manager Blackrock, a key advocate of this practice, is among the private investors joining Planet’s SPAC transaction, alongside Google and Salesforce founder Marc Benioff. “BlackRock has said you’re not really an investable company if you don’t track your ESG scores,” Niccolo de Masi, the investor who led the SPAC taking Planet public, said last week. “Planet helps companies do that.”

“The world needs this, we’re feeling this pull, the transition out of the Covid-induced recession into a new economy, everyone trying to switch to digital economy, every industry switching to a sustainable economy,” Marshall says. “Our data is very mission critical to those companies, it’s not like they can walk away. It’s about seeing threats around the corner, it’s about companies with fundamental efficiency maneuvers without which they can’t the competitive, civil governments doing regulatory enforcement they can’t do without our data. Every company is measuring their ESG target. Every country is measuring emissions.”

Planet is still a risky technology company by normal standards; it’s currently investing in growth and doesn’t forecast profitability until 2025. One concern for investors might be the company’s debts of $147 million, although that will be reduced by some of the money raised in the current transaction. Much of the rest of the proceeds, Marshall says, will be used to hire salespeople to expand their customer base, and software engineers to develop better tools for their customers. The company’s satellite fleet is largely established, although it will need to be continually refreshed with new spacecraft every few years.

The goal is to scale Planet up, like a “normal” digital start-up. It’s not a test of a novel new luxury good or infrastructure to boost space activity. It’s a test of whether data gathered in space is as valuable as information gathered by your mobile phone or Google’s searches. In other words, whether space business is just regular business, after all.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery Interlude

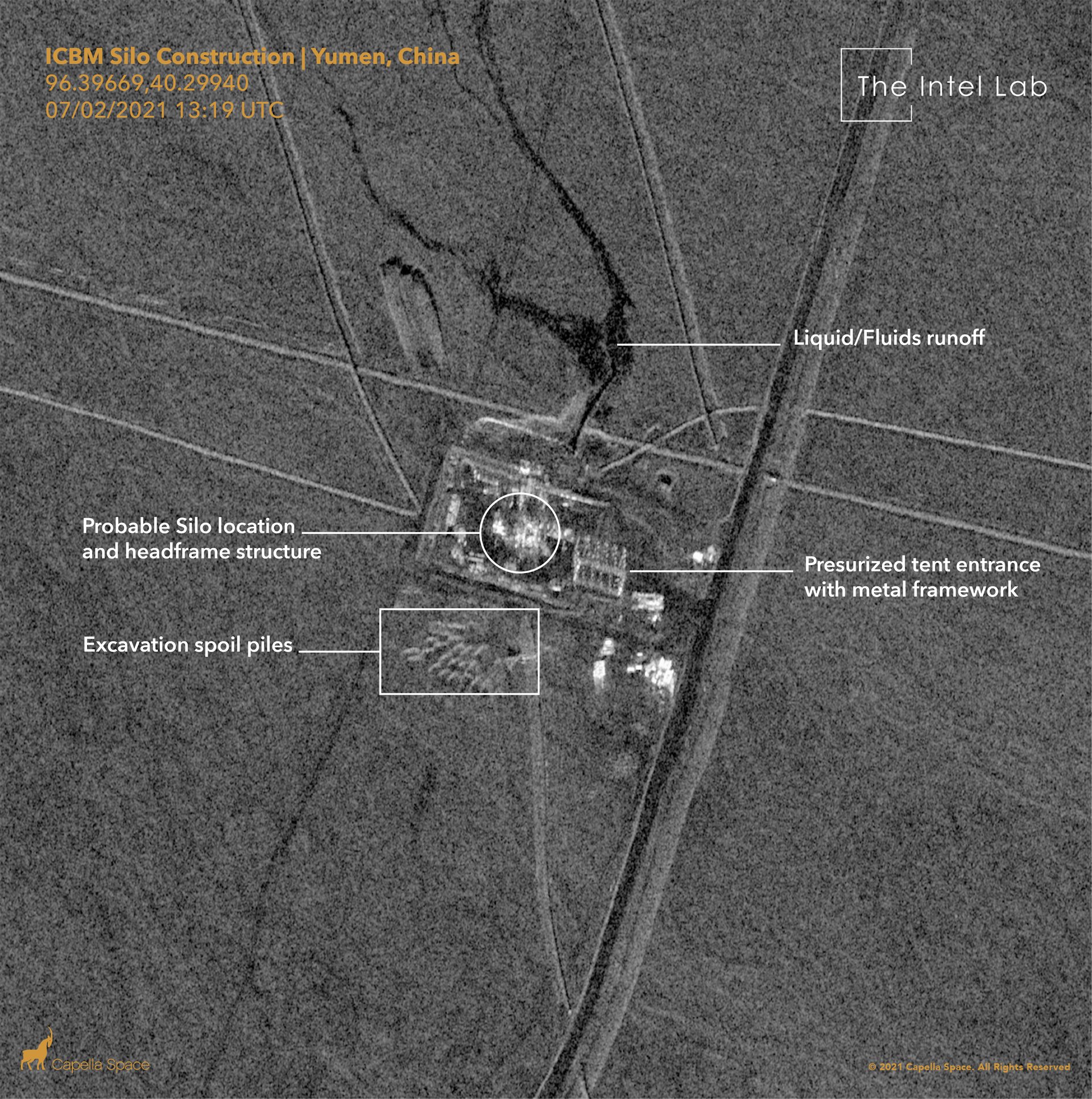

The importance of commercial satellite imagery was underscored again when analysts at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, an affiliate of Middlebury College, discovered a massive new build-out of ballistic missile silos in China, something that wouldn’t have been possible a decade ago. The next big thing is satellite radar, which can peer inside some structures—including the “bouncy castles of death” used to cover the silos as they are built. Analysts at the Intel Lab, a firm that provides intelligence analysis of open-source data, annotated this image, which shows the hard structure within the tent being used to excavate the launch site:

👀 Read this 👀

A key part of Planet’s going-public pitch is the rise of do-gooding investors, under the banner ESG. As global firms come under pressure to demonstrate that they are living up to this new ethic, companies like Planet are positioned to help them verify this with hard data. Quartz’s latest field guide dives into this key investing trend. Here’s a quick breakdown, by the numbers:

~$40 trillion: Money held in ESG assets worldwide

$53 trillion: Total of ESG assets worldwide by 2025, according to Bloomberg Intelligence

⅓: Proportion of global investments that could be ESG by 2025

90%: Millennials active in the markets who say they believe in sustainable investing, according to a 2019 study by Morgan Stanley

$285 billion: How much ESG funds grew in 2020 alone, a 96% increase over 2019

🛰🛰🛰

SPACE DEBRIS

Momentus settles fraud charges. The saga of Momentus, a company with dreams of going public and launching a space tug, has taken a new turn as the company and its investors are paying $8 million to settle charges of fraud. The company’s controversial Russian founder, Mikhail Kokorich, did not participate in the settlement and is the subject of SEC fraud charges. Currently in Switzerland, Kokorich denies these allegations. I reported on the federal investigation into Kokorich’s access to restricted technology in November but the SEC cites internal communications that show Momentus’ propulsion system failed orbital tests, even as the company touted it publicly as a success. There’s some irony: Momentus’ problems emerged because its technology was deemed too critical to be used by foreign nationals, but the tech apparently didn’t even work.

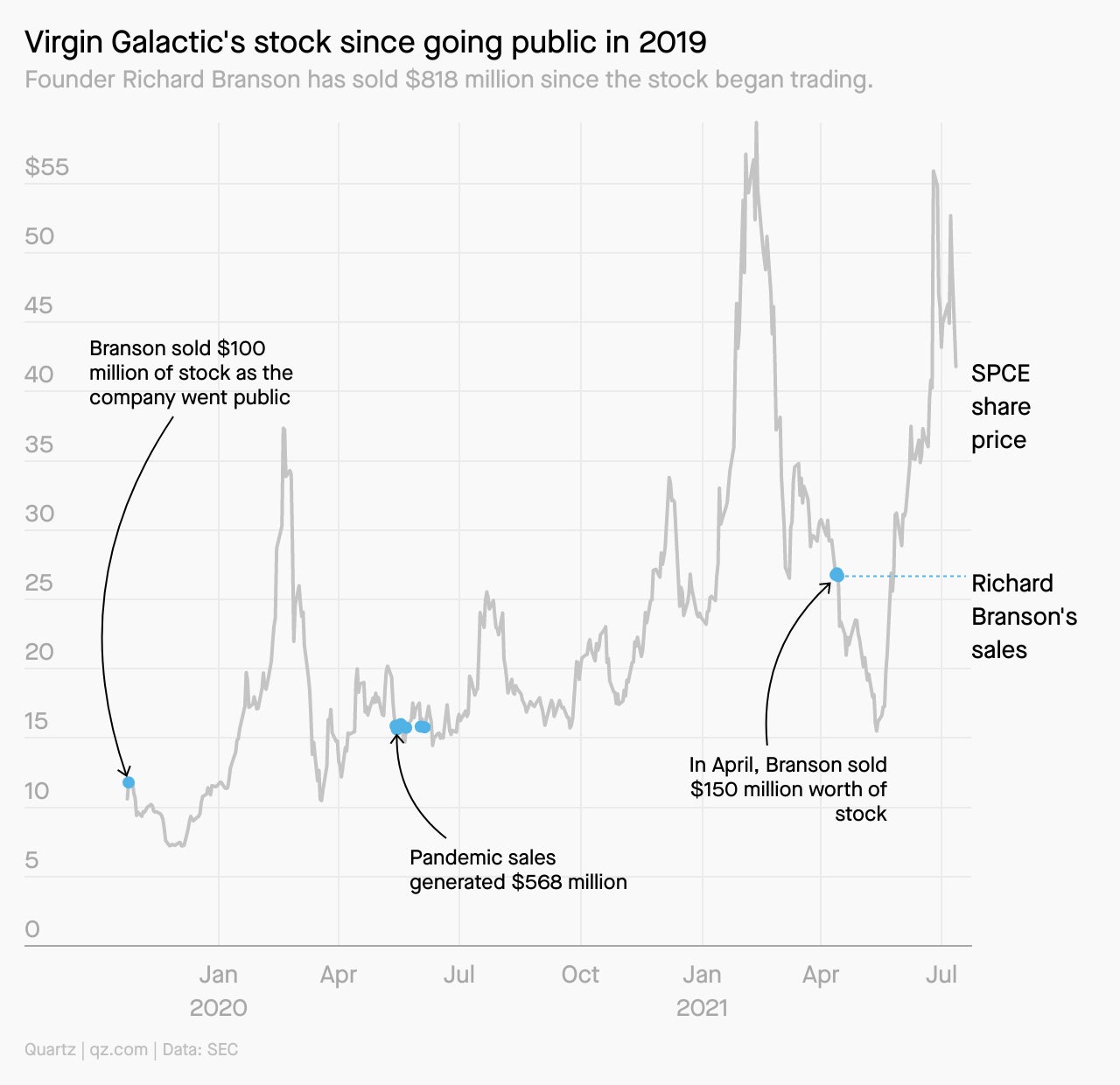

Branson in space. The tycoon went to space on July 11 in Virgin Galactic’s rocketplane, keeping his promise to ride the vehicle before it enters regular passenger service. Still no word on when that will be, but it’s worth highlighting how Branson’s bet on space tourism has paid off. After Galactic went public in 2019, he was able to sell enough stock to bolster other businesses that suffered during the pandemic, and is still sitting on a $2.3 billion stake. Now, the firm is raising $500 million by selling new shares, which will bolster the chances for regular suborbital tourism:

Bezos in space. Our other edge-of-space-bound billionaire, Jeff Bezos, will launch on the New Shepard July 20, alongside his brother and Wally Funk, an 82-year old aviator denied a chance to fly with NASA at the dawn of the space age. Still no word on the identity of the passenger who paid $28 million to Blue Origin’s charity, the Club for the Future, to join the crew. Blue did announce $19 million of that cash will be donated to a variety of space-focused non-profits. This is laudable stuff, particularly for organizations working to bring underrepresented groups into the aerospace industry. Still, given the largely negative public reaction to this round of billionaire suborbital tourism, it feels like Blue is wasting a huge opportunity to explain to the public at large why this new model of space exploration matters to people who care more about the earth.

Amazon, the last space FAANG? A group of Facebook engineers with a satellite focus was snapped up by Amazon to bolster the ranks of its Kuiper satellite network team. The transaction highlights the urgency Amazon is putting on its planned mega satellite-constellation, but also the difficulty of integrating a space business into a big digital company. Facebook and Google have made various efforts to launch and operate satellites before ending those projects, while rumors of Apple’s satellite plans have dried up. That may leave Amazon as the last internet company with its own satellite project.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 100 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your predictions for Planet’s IPO, the case for suborbital tourism as a transformative business, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].