Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Defining lunar down, MOOSE, and Astra buys some rocket engine IP.

🚀 🚀 🚀

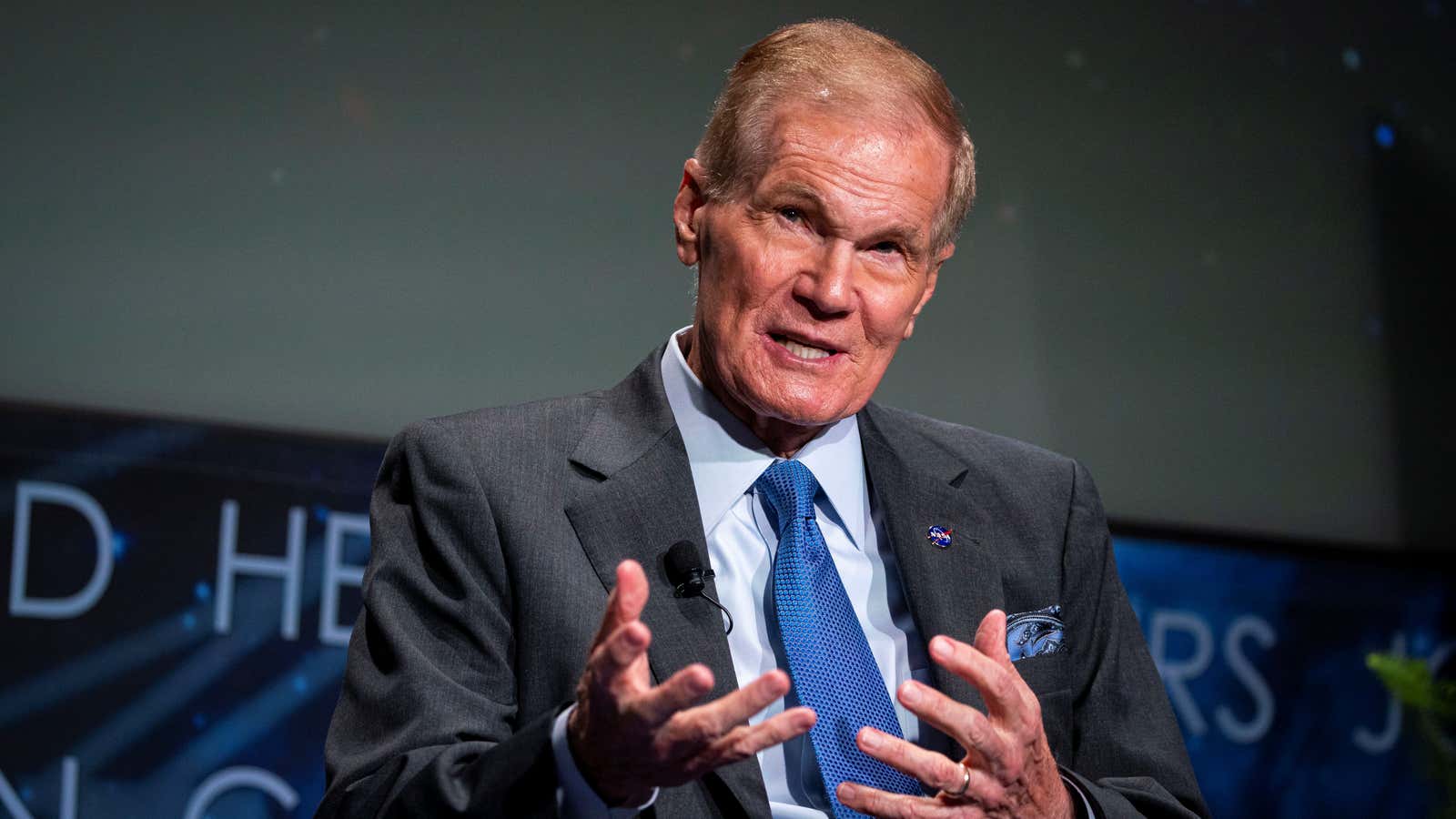

This week, NASA split its human spaceflight division in two.

Administrator Bill Nelson said one directorate would focus on operational activities in space, and the other would develop new technologies and concepts for future missions. In effect, the move separates NASA’s work in low-Earth orbit from decisions about how the space agency will return astronauts to the moon through the Artemis program.

This is not an unusual structure on its face; a similar organization was used by NASA prior to 2011, and the US military separates the people responsible for developing and testing new technology from those who operate it.

Instead, the decision is controversial because of its context: It removes responsibility for plotting out the Artemis mission from associate administrator Kathy Lueders, who previously oversaw all human spaceflight programs, and now will focus on operations. A former NASA official, Jim Free, came back from the private sector to take on the job of developing plans for going to the moon and Mars.

Lueders is respected inside and outside of NASA for seeing through the space agency’s work with private companies to fly cargo and astronauts to the International Space Station. The Artemis architecture has adopted some components of those partnerships, hiring private companies to put robots on the moon, ship supplies there, and build the landers that will carry astronauts to the surface. But after she awarded a lunar lander contract to SpaceX, Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin challenged her decision and took NASA to court, adding months, at least, of new delays.

Now, she’s been replaced by Free, who boasts decades of NASA experience, but mainly in traditional NASA programs, including Orion, the over-budget spacecraft that is expected to take astronauts from Earth to lunar orbit. Deals that guarantee profits and include extensive NASA requirements are beloved by contractors and lawmakers who prioritize in-district spending by the space program. Some observers, including NASA employees, see the split as a sign the space agency is turning away from the only model that has delivered working hardware in recent years.

Nelson denied this is the case, insisting the decision was “obvious” because the portfolio of human spaceflight activities, about half of NASA’s annual budget, could not be managed by one person. Lueders and Free said they would, by necessity, work closely together, but ultimately the path forward will be set by the official developing plans and issuing first contracts.

And how about that 2024 landing date?

Observers of the space program had expected Nelson to deliver some of kind of update on the return to the moon, perhaps the long-awaited acknowledgment that a moon landing in 2024 isn’t feasible. Asked about timing, he offered a sleight of hand.

“Artemis 1 will be at the end of this year or the first part of next year,” he said. “Then we are going to the moon with humans in late ’23 or early ’24. Then, if you have a coin, you can flip it, as to what’s going to happen with the legal wrangling that’s going on right now…once we have answers about that, we can answer about Artemis 3 or Artemis 4.”

The second Artemis mission, to fly astronauts in an obit around the moon, was originally planned for 2022 or 2023, ahead of Artemis 3, which was to put humans on the surface in 2024. Nelson appeared to suggest that NASA would act as if the orbital mission fulfilled its initial proposal. I asked if it is NASA’s view that an orbit around the moon would fulfill the agency’s promise to land by 2024.

“Do you remember Apollo 8?” the 78-year-old former senator replied, referencing the 1968 test mission that saw the first humans orbit the moon. “It was humans going to the moon for the first time…the pictures of the moon looking back at Earth, a perspective we had never had, that was a major achievement. After Apollo 17, we have not been back to the moon. We are, in Artemis 2, [launching] a mission that will be…way out beyond the moon, further than any human has ever been.”

It wasn’t quite an answer, but it’s a far from the original promise of Artemis as articulated by Nelson’s predecessor: “What we don’t want to do is recreate Apollo.”

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery interlude

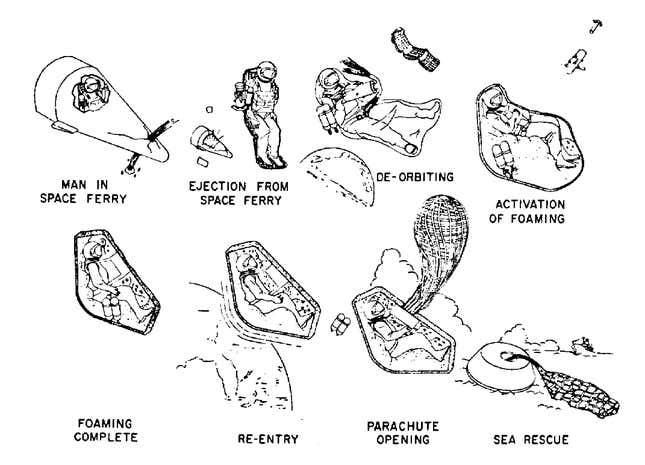

In the annals of space technology concepts, few designs combined clarity with hilarity as well as MOOSE, or Man Out of Space Easiest, a scheme cooked up by General Electric in the 1960s for an individual space escape pod. If an astronaut needed to return to Earth in an emergency, they could create a personal reentry vehicle out of foam. It’s as simple as this:

As you might imagine, this plan was never demonstrated in reality, although some of the necessary components were tested on orbit. A hat tip to Ben Brockert for sharing this idea.

🛰🛰🛰

Space debris

Why does Astra need to buy rocket engines? The publicly-traded rocket maker Astra space is purchasing engine designs from a competitor, Firefly, in order to meet its promise to deliver a launch vehicle that can carry 500 kg to orbit. Astra has struggled to launch satellites successfully, with its most recent attempt last month ending in failure, and its decision to use a rival’s technology demonstrates the high level of competition and pressure to consolidate faced by rocket builders.

How can space billionaires fix their image problem? The Secretary General of the United Nations cited luxury space tourism as a symbol of global inequality.

Why hasn’t Elon Musk been to space yet? He’s not impressed with the activities available in low-Earth orbit, among other reasons.

Is China plotting orbital weapons? The US defense official in charge of space warned that China might be developing orbital weapons, though he has no specific evidence. Scare-mongering can boost investment in US military space, but arms control expert Jeffrey Lewis argues that American missile defenses would make space weapons attractive to US rivals.

When will the International Space Station be retired? Lawmakers heard testimony that the ISS, which is only funded through 2024, will be structurally sound until at least 2028. As China ramps up its activities in low-Earth orbit, defense analyst Todd Harrison argued the civil space station should remain in place as a diplomatic tool.

Are private space stations the future? NASA, at least, hopes so, and says it is evaluating numerous proposals for a planned $400 million in development funding.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 108 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your takes on NASA’s human spaceflight reorganization, kooky space concept art, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].