Google is moving faster than US regulators to get deepfakes disclosed in political ads

Voters need to know when a political ad is using AI

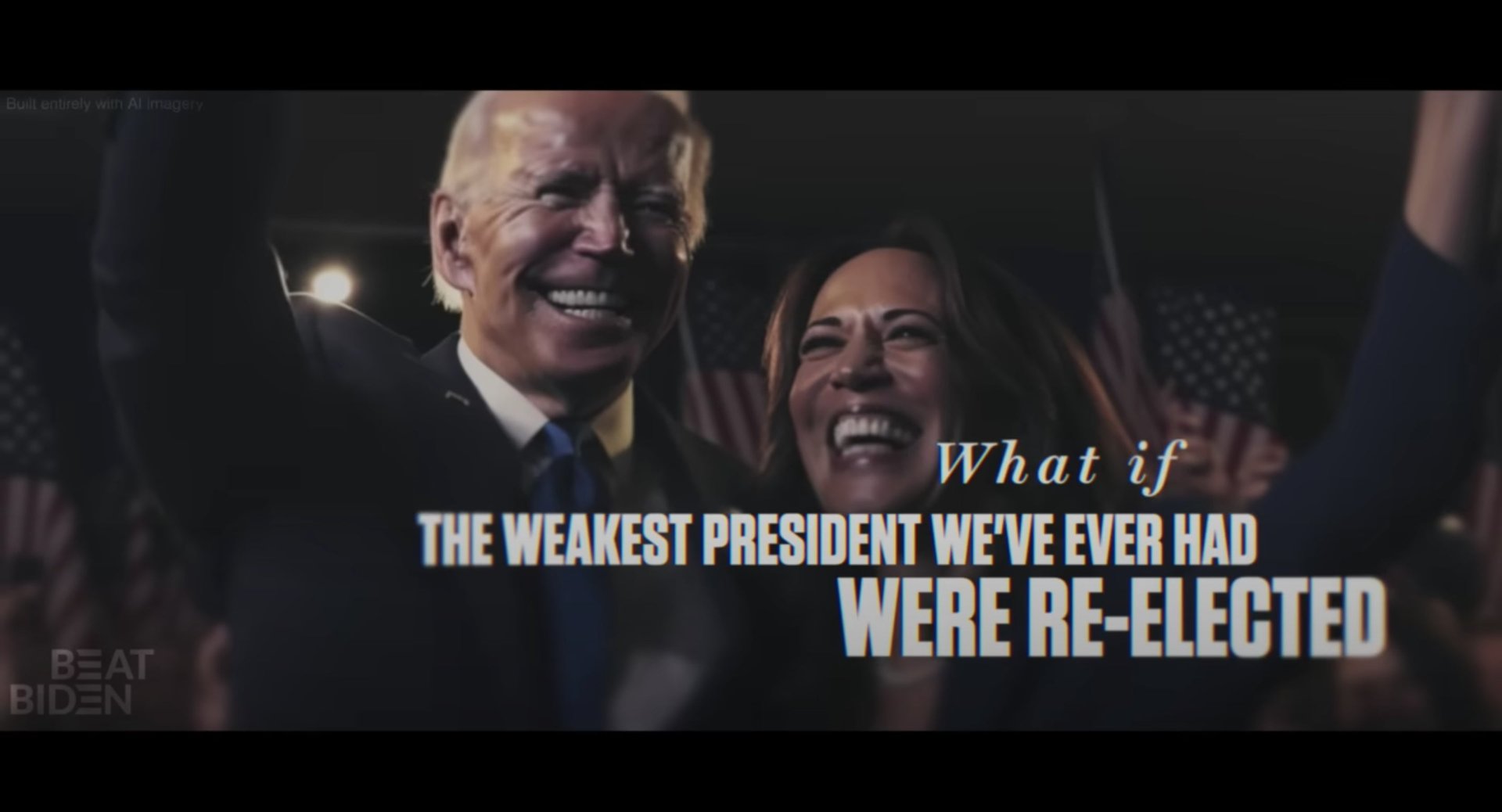

In April, the Republican National Committee (RNC) debuted an ad depicting its vision of what would happen if Joe Biden won reelection to the US presidency in 2024: China would invade Taiwan, the financial system would collapse, undocumented immigrants would swarm into US borders, the city of San Francisco would collapse into crime- and drug-induced chaos.

Suggested Reading

When the dystopian-themed commercial ended, a fine-print disclosure flashed on the upper lefthand corner of the screen: “Built entirely with AI imagery.”

Related Content

This disclosure was voluntary. The RNC didn’t need to disclose anything because there are no US laws on the books mandating that political advertisers tell voters when they use AI-generated images, video, or audio.

Now, Google is racing ahead of government regulators by mandating that any political ad on its platforms have a written disclosure if it uses AI-generated images, video, or audio.

US senator Amy Klobuchar, who introduced a bill to mandate these kinds of disclosures federally, applauded Google’s rule change, but said ad sellers need more than voluntary commitments to keep them in check. “Voters deserve nothing less than full transparency,” she said.

Slow AI progress in Congress

Five months after the RNC ad debuted, little has changed.

In May, Klobuchar, along with fellow senators Cory Booker and Michael Bennett, proposed legislation that would “require a disclaimer on political ads that use images or video generated by artificial intelligence.” US representative Yvette Clarke proposed a similar law in the House.

“Our democracy relies on transparency and accountability, especially when it comes to political advertising,” Booker said at the time. “We must ensure that voters are fully aware of the source and authenticity of all political ads that seek to inform voters’ decisions.”

The bills have not progressed at all.

But in August, at the insistence (pdf) of a group of lawmakers and advocacy groups, the US Federal Election Commission (FEC) decided it will begin the rulemaking process on AI-generated content in political ads by asking for public comment.

Was your ad made by AI?

The RNC’s scaremongering ad uses computer-generated images, likely from an AI generator like DALL-E or Midjourney, to bring this political horror to life. But at least it has a disclosure.

Another ad, from Florida governor and US presidential candidate Ron DeSantis, released in July, used an AI-generated Donald Trump voice in an attack ad against him. The text that the voice reads is real—Trump posted it on his social media website Truth Social—but the voice is a computer-generated imitation. This ad had no disclosure.

Should lawmakers allow deepfakes in political ads at all? That’s a good question—and one for them to discuss. In the meantime, voters are gathering information about candidates. They deserve to know what’s real and what isn’t. Simple disclosures can help, though maybe they should be a bit larger than the one in the RNC ad. And perhaps they should be vocalized and not just a visual disclosure.

Americans have broad freedom of speech, but there are special rules that govern both commercial and political advertising. For starters, we get to know whether something we’re seeing is an advertisement or not. If you see a celebrity hawking a new cream on Instagram, for example, they are legally required to disclose to their followers if they’re being paid to promote it.

In politics, commercials must tell us who paid for a given ad and whether it’s coming from a specific political candidate—hence the common sign-off of “I’m so-and-so and I approve this message.”

The advent of generative AI and deepfake technology—which will only improve in quality in the years to come—necessitates better explanation of how our political ads are made. When the voice and face of a politician can be imitated, the risk for deception is far greater than usual.

Voters have the right to know if what they see and hear in their political ads are real—or if they were made by AI.