India’s Narendra Modi government likes setting ambitious targets for itself and the country.

These range from housing to every Indian to allowing only electric vehicles on Indian roads to digitising its $2.5 trillion economy.

While aiming high is welcome, it is also imperative that realistic roadmaps are laid down along with well-grounded planning. The latter can be challenging as Team Modi has probably figured out by now.

Here’s a look at some of the mega schemes it has announced since taking power in 2014 and how these have played out:

Electricity for all

On Sept.25, the prime minister unveiled the Saubhagya scheme. Alternatively called the Pradhan Mantri Sahaj Bijli Har Ghar Yojana, it aims to provide free electricity by the end of 2018 to some 4 crore people or 20% of the country’s households still living in the dark.

Some, though, likened it to old wine in a new bottle.

For two earlier plans—one launched in July 2015 and an earlier one initiated by the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government in 2005—sought to provide free power to people living below the poverty line (BPL). Those schemes were flawed.

The government could declare a village electrified even if only 10% of its households/establishments had power connections. So 99.37% of Indian villages were declared “electrified” as of June 2017, even though some 4 crore people didn’t have access to electricity.

The latest scheme, even though building on the earlier ones’ groundwork, may still not be easy. “The plan is ambitious and the time frame is limited. Power has reached the villages already…now the government has to ensure the last mile connectivity,” explained Vivek Jain, associate director at India Ratings and Research, a credit rating firm.

The rise of India’s per capita income

Niti Aayog, the government’s think-tank, has come under fire for often setting unrealistic time frames for its plans. One such was to increase India’s per capita income from Rs1.06 lakh ($1,610) annually in 2015-16 to Rs3.14 lakh in 2031-32.

To grasp its scale, let’s see what it implies: By 2032, the whole of India could afford private vehicles and will have access to air-conditioners. This is in contrast to India in 2012 where one out of every five citizens is poor, only 21% of the population has access to lavatories, and only 6% gets tap water.

Is it a tad unrealistic, since 363 million Indians lived below the poverty line in 2014?

“It is not that this isn’t achievable. China did something close to this but they did it with this state-led industrialisation drive, increased investment for growth etc,” said Jayati Ghosh, a professor with the New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University. “In India, instead, we are spending less on infrastructure and social infrastructure. So how is it going to be achievable?”

Housing for all by 2022

The Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) launched in June 2015 aims to build homes—with water and power supply and sanitation facilities—for everyone by 2022.

The government is offering financial assistance for this and has re-designated affordable housing as infrastructure to make access to bank loans easier. The scheme saw initial success and is being reviewed so that it is sustainable.

However, roadblocks remain.

“The demand is high and the rate at which it is being met is slow. The government needs to decentralise it (the scheme)…at the moment building a house is fraught with red-tape,” according to Shreya Deb, principal investments, at Omidyar Network, a philanthropic investment firm.

As of April 2017, 1.88 million urban houses have been approved and roughly 0.1 million built, even as the shortage was estimated to be around 18.78 million between 2012-2017.

Electric cars by 2030

By 2030, Asia’s third-largest economy is gearing up to sell only electric vehicles (EVs).

Nearly 21 million vehicles are sold in India today, including cars, bikes, and scooters. Of these, EVs form just about 22,000 units.

So the government’s task is cut out.

EVs remain expensive, particularly because of their batteries. In terms of mileage, they average a meagre 120km on full charge in India. Moreover, the virtual absence of charging points across the country puts off potential customers. Then there is speed, rather the lack of it: The top two India-made, battery-powered cars do an average top speed of just 85km/hour.

“Getting to 100% e-vehicles over the next decade is unlikely, but I do expect it to be a significant share of the market,” Yaquta Mandviwala, a partner at Boston-based consultancy firm, Bain & Company, had earlier told Quartz.

Long path to roads

When it assumed power in 2014, the Modi government promised to revive the roads sector, stagnating since 2012. It promised to build 30km of roads a day, later raising the target to 41km in 2016.

For this, it relied on the tried-and-tested engineering, procurement, and, construction (EPC) model. As per this model, the road is to be laid down by a private developer but funded by the government. It also devised the hybrid annuity model wherein the government took care of 40% of the project cost and the rest came from the contractor.

But as of February 2017, it built only 22km of roads a day, though it was up from 16km a year before. This year, it has set a target of 41km. In addition, over the next two years, India’s National Highway’s Authority, the nodal agency to construct highways in the country plans to add 20,000km to the highway network, taking the total to 50,000kms. All that would be far-fetched, not the least because of perennial hurdles like land acquisition and funding.

“In the last six months, they certainly have fallen short of the target announced,” Vikash Sharda, director for capital projects and infrastructure at consultancy firm PwC, told the DNA newspaper. “Even if they focus on gaining more ground during the second half of this year, they still might fall short of reaching 41km daily.”

Solar isn’t too bright

In 2015, the Modi government set about transforming India’s solar energy sector.

From the four gigawatt (GW) installed capacity that year, it wanted to produce up to 100GW by 2022, looking to attract a staggering $100 billion during the period.

Two years since, India’s solar power generation capacity stands at 12GW and the government is looking to raise it to 22GW by March next year. Over the past year, tariffs have nosedived by 50%, bringing them to a level cheaper than coal-powered electricity. Much of that is due to aggressive bidding. Questions now linger over the viability of these solar projects.

Meanwhile, the 2022 target could be out of bounds.

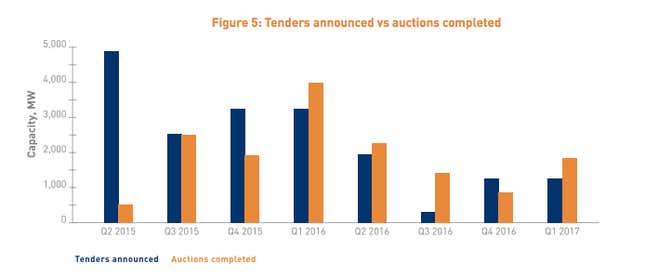

According to market research firm, Bridge to India, only 44GW of cumulative capacity is likely to be added in India until 2021. “We expect slowdown in 2018 because of lull in recent tender activity but demand is expected to pick up again from 2019 onwards,” a report from Bridge to India said (pdf).

Killing cash

Boosting digital transactions was supposedly a key objective in demonetising the Rs500 and Rs1,000 currency notes in November 2016.

The acute cash-crunch that followed naturally provided an impetus to digital modes of payments. Buoyed by this, the government set a target of 25 billion digital transactions for 2017-18 through its newly-launched Unified Payments Interface, USSD-based payments (allows basic banking through text messages and calls), Aadhaar pay, Immediate Payment Service, and debit cards.

This would help curb the circulation of unaccounted money.

However, a lack of infrastructure could be a big hurdle, believe experts.

“You need certain basic factors for the ecosystem to grow so that people can adopt digital money and I don’t believe that still exists. Therefore, I think the government is going to miss the target by a big margin as I believe that they won’t be able to cross more than 20-21 billion transactions via these mediums,” Sidharth Deb, associate at Koan Advisory, a research based advisory firm, told Quartz.

A number of payment systems still don’t allow money transfer from one network to the other, Deb said, and that poses a huge challenge.