With the fall of Harvey Weinstein, Hollywood is finally being called out for its sexist dynamics. Women seem closer to finally being recognised for their role in the industry; they demand to be fairly represented—through female-led plots, and by having more movies written and directed by women.

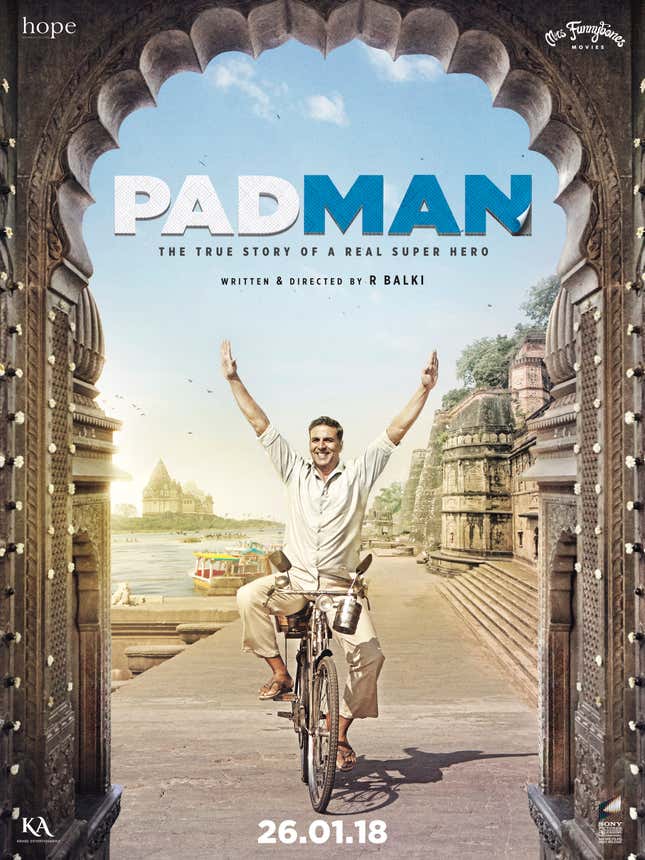

But in Bollywood, the latest production to carry forward a feminist message isn’t a story about a woman: It’s Padman, a movie inspired by the story of Arunachalam Muruganantham, an illiterate man from Coimbatore who brought about a small revolution for low-income Indian women by inventing a low-cost machine to make sanitary pads.

The movie, starring Akshay Kumar and Sonam Kapoor, is written by Twinkle Khanna (who is married to Kumar) and adapted from her story “The Sanitary Man of Sacred Land,” featured in the collection The Legend of Lakshmi Prasad. Khanna is also one of the producers of the movie.

For low-income women all around the world, the lack of sanitary pads, toilets, and access to clean water represent a huge barrier: Too many girls end up dropping out of school, for instance, because they don’t have supplies to manage their periods, or even toilets. This in turn feeds the taboo around menstruation, generating a vicious circle.

But if anything can change perceptions in India, it is Bollywood—and this is what Padman is set to do.

With some creative liberties, the book and film tell the story of “India’s Menstrual Man,” and of his stubborn quest to make pads affordable for women who can’t buy those made by large corporations.

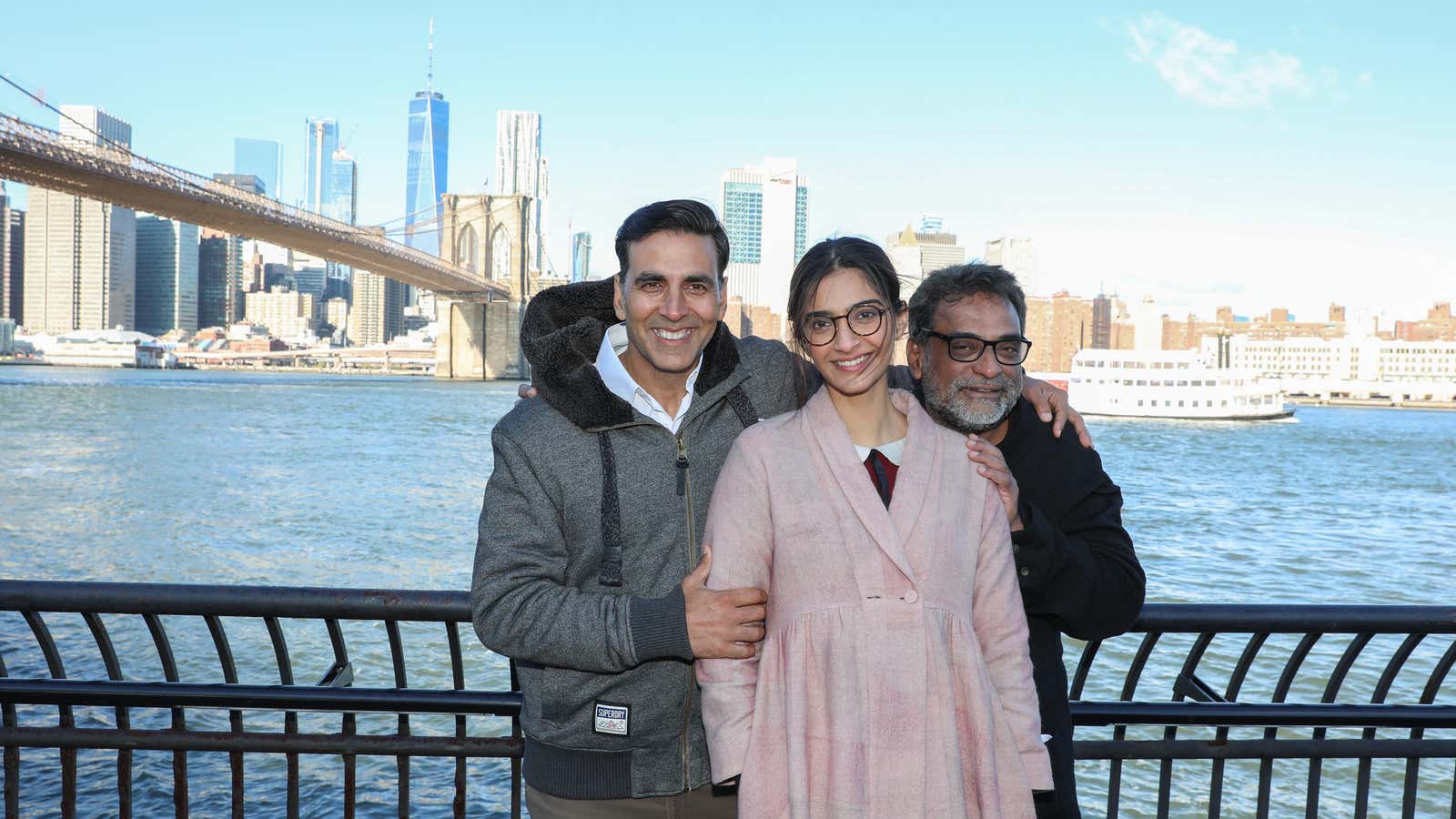

“It’s the story of a man in ordinary circumstances who creates an extraordinary invention,” Khanna told Quartz during an interview alongside Kumar and Kapoor in New York at the Taj Hotel, where the cast is (rather classically) staying while some of Padman‘s scenes are shot in the city. These are, Khanna believes, the kind of stories Bollywood needs—”content-driven” movies, as she and her team refer to them, as opposed to entertainment-driven.

Though Padman‘s story deals with what is considered a women’s issue, Khanna isn’t comfortable with classifying it based on the fact that it addresses a fundamentally female matter.

Khanna doesn’t think Bollywood needs female-centered stories. Rather, “we need to tell good stories, and that is where I feel somehow we’ve been failing,” she said, adding, “Unfortunately we have few good writers […] so the need is to have good writers, good stories, and to be able to tell them effectively.”

In that, her feminist discourse differs quite starkly from that of high-profile American women, particularly in Hollywood, where gender representation (of directors, actors, writers, and protagonists) is a much stronger focus.

Kapoor has a much less critical take than Khanna. She is defensive of Bollywood (after all, it’s her family’s business), and doesn’t as much as entertain the idea that it might be a particularly sexist industry: When asked about stereotypical gender roles and objectification in today’s big movies, she is quick to push back by mentioning the strong female leads of the “golden age” of Indian cinema.

“Obviously there is a fair amount of sexism in every industry in the world,” she says. “Film and art are just a reflection of what society is.” Kapoor does believe that films with feminist messages can have an impact on society, but doesn’t think it has anything to do with females playing lead roles. Padman is the case in point, she says, casually rubbing the foot she’s taken out of her Manolo Blahnik stilettos. “It’s a story about a man who is a true feminist […] and sends a very strong message to women, that [they] cannot be ashamed of who [they] are.”

But Padman isn’t aiming to shock, either. Khanna is clear that it is chiefly a story of quintessential Indian ingenuity, of the journey of ”an illiterate man, an innovator, and an inventor.” A lot of care has been taken in the movie to treat menstruation as just any other thing. “It’s the first five minutes when you get a little bit of a shock which is necessary but after that…he could be making a plastic bottle,” Khanna says.

It may be perceived as shying away from a difficult subject but normalising menstruation through the power of jugaad (low-cost alternatives), and treating it just like any other market problem, might just be the way to do it. Of course, it’s impossible yet to say whether the film will deliver, and if it indeed will change minds. We’ll find out by Jan. 26, when Padman releases.