Driving in India follows a set of unwritten rules, which of course are at odds with the actual rules. Many may even confuse the right of way as a constitutional right, judging by the anarchy one witnesses on the streets. As it turns out, in a prevailing culture of corruption, individuals find it easier to bend the rules, rather than follow the prescribed norms. Insights from game theory tell us that individuals act in a manner to maximise their return.

This implies that our incentives are aligned towards bending the rules rather than following them. We constantly blame corrupt politicians and bureaucrats. However, many of us don’t realise that our collective actions as a society let corruption persist and even encourage it. Insights gained from behavioural economics suggest that corruption in India is encouraged by individuals seeking to further their self-interests. In certain situations, the costs involved in acting according to the prescribed rules are often greater than the costs involved in bending the rules. Thus, corruption in India can be thought of as a collective action problem. With pervasive and persistent corruption, the incentives for individuals to act in a non-corrupt manner are diminished greatly, whereas the incentives to follow the “rules of the game” are greater. Not only does corruption result in a transfer of resources, it also has the effect of distorting allocations.

In a recent survey of corruption in Delhi, nearly one-third of the households sampled had paid a bribe over the past year, whilst 26% of the households had first-hand experience of corrupt practices at the regional transport offices (RTOs). An interesting result was that first-hand experience was nearly negligible in utilities such as LPG, gas, and water supply. Another disturbing result was that the highest service denial rate was in driving licences. Service denial means that a public service has been denied over non-payment of bribes. Even the union transport minister Nitin Gadkari has termed RTOs as “hotbeds of corruption who have looted more than Chambal dacoits.” He further stated that nearly a third of the licences issued in India are fake.

Some studies have attempted to explore the link between poor driving and corruption. Comparing World Health Organization’s 2013 data on road deaths per 1,00,000 and scores on Rule of Law by the World Justice Project, James O’Malley finds a strong correlation between the two.

Countries scoring low on rule of law had more road deaths per 1,00,000 than those which scored higher.

Corruption and social outcomes

Corruption is generally viewed as a transfer of resources from citizens to bureaucrats. However, Bertrand et al. show that it distorts allocations as well. Studying the allocation of drivers licences in New Delhi, the authors are of the opinion that policies, too, are distorted with prevalent corruption.

In their experiment design, drivers seeking licences were divided into three different groups—a comparison (base) group, a bonus group, and a lesson group. Drivers in the bonus group were offered a cash prize if they managed to obtain a permanent licence within 32 days of securing their temporary licence. The base group were asked simply to obtain a licence and appear for a follow up survey, for which they were paid Rs800. Drivers in the bonus group received Rs800 and a Rs2,000 cash prize. Those in the lesson group were simply offered free lessons.

The results obtained were quite startling.

Over 70% of those in the bonus group were able to obtain licences, whilst the number stood at 48% for the comparison group. Furthermore, 74% of those in the bonus group did not bother to learn how to drive. An interesting result is also that approximately 80% of drivers in both the comparison group and the bonus group employed agents. Furthermore, of those that hired agents, only 23% went through the prescribed driving test, whilst 89% of the comparison group took the test. In order to test whether corruption in the licensing process put more unsafe drivers on the road, the authors administered a surprise driving test at the time of the follow up survey. Over half of the bonus group failed the driving test, indicating that hiring agents is the main channel through which bad drivers are able to obtain licences.

The above is an example of how corruption has led to an increasing number of unsafe drivers on the road. Individuals acting in their self-interest hire agents to expedite the process of obtaining licences. The agents, acting in collaboration with bureaucrats are able to “simplify” the process of obtaining a licence. However, with such individuals acting in their best interest, society as a whole is worse off, as there are more bad drivers on the road

[…]

Social cooperation

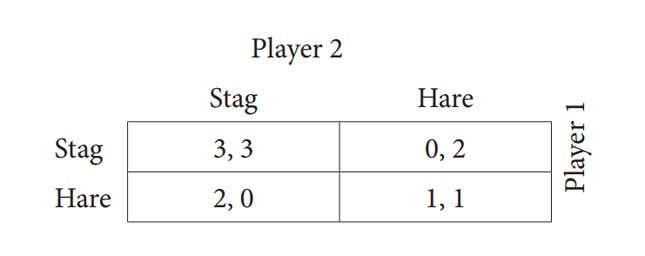

The classic stag hunt game can be thought of as an analogy of social cooperation. Imagine the following scenario: Two individuals go for a hunt; where they can each hunt for a stag or a hare. Here’s the catch: neither knows what the other will do. The stag is a more desirable option for a meal. However, it will take two of them to trap the animal. Individually, both are able to catch a hare each, but will remain unsatisfied. Does each player think the other will join the hunt for the stag? Or does each of them expect the other to go for the hare? This situation is illustrated below. As it can be seen, if both players hunt the stag, then each receives a payoff of 3. If both hunt the hare, then each receive a payoff of 1.

One would think the best option for both hunters would be to pool their resources. However, this would require that the two hunters trust each other. Expectations as to how the other player would act play a key role in the hunters’ decision-making. If both trust the other to join the hunt for the stag, then we would have a socially optimal outcome. On the other hand, if one hunter decides to go for the stag and the other for the hare, then the first hunter remains hungry. Rather than going hungry, each hunter could be expected to hedge their bets and pick the safe option with the hare.

Extending this analogy, imagine the situation in any RTO in India. A person seeking a licence has two options: go through an agent or go through the correct channels. By going through an agent, the person is likely to obtain a licence quicker, and may not have to go through the driving test.

On the other hand, going through the proper channels would require an investment in time. Now, in deciding what path to take, this person is likely to consider how others in the same position had acted. If everyone went through proper channels and cleared their driving tests, then Indian roads would be much safer to drive on.

However, if each player in this game expects others to pay an agent and not go through the driving test, then why would he bother spending his time in going through the right channels? This example can be extended to the delivery of many public services in India.

Excerpted with the permission of Rupa Publications from On the Trail of the Black Tracking Corruption, edited by Bibek Debroy and Kishore Arun Desai. We welcome your comments at [email protected].