Climate change is taking a toll on India’s agricultural productivity—and farmers’ incomes—the economic survey 2018 shows.

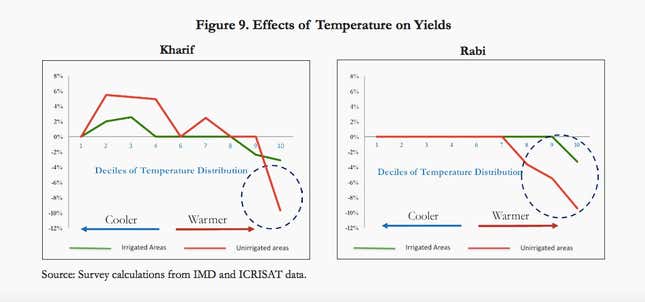

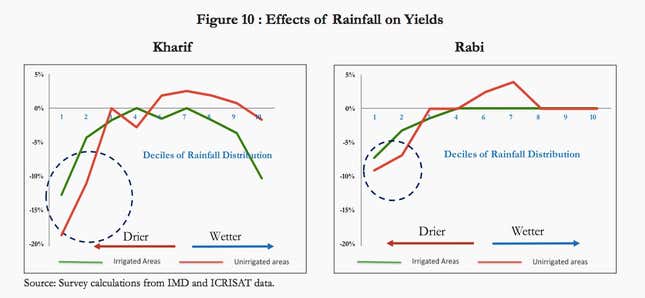

Chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian and his team have found that the impact of temperature and rainfall on agriculture is felt during extreme changes—when temperatures are much higher, rainfall significantly lower, and the number of “dry days” greater than normal.

The charts below show how the impact of climate change remains nearly zero as long as the variations aren’t extreme.

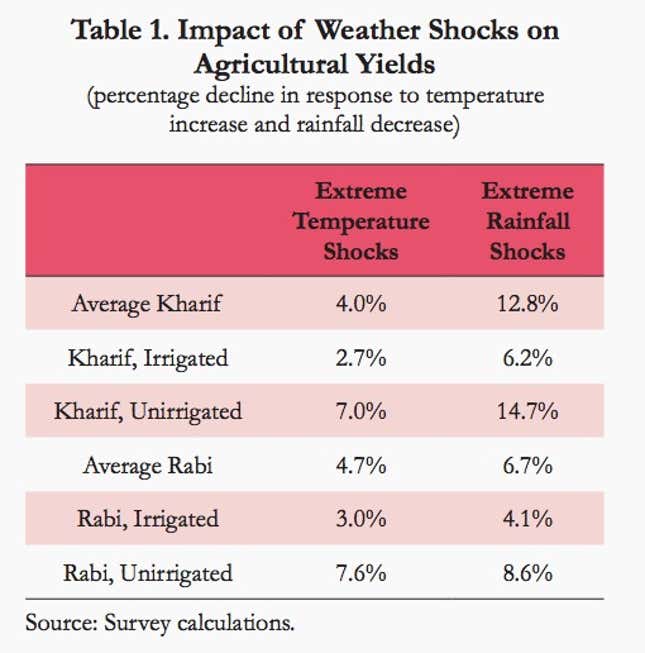

The economic survey noted that such impact is more adverse in unirrigated lands compared with irrigated areas. “Extreme shocks have highly divergent effects between unirrigated and irrigated areas (and consequently between crops that are dependent on rainfall), almost twice as high in the former compared with the latter,” the survey said.

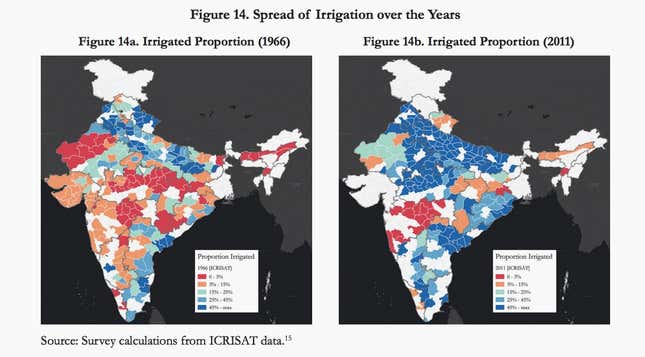

And given the fact that around 52% (73.2 million hectares area of a total 141.4 million hectares net sown area) of India’s total land under agriculture is still unirrigated and rain-fed, the sector could be in trouble.

The change in agricultural productivity patterns as a result of climate change could reduce annual agricultural incomes by between 15% and 18% on average, and between 20% and 25% particularly for unirrigated areas, the survey says.

Climate change models, such as the ones developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), predict that temperatures in India are likely to rise by between 3 degrees Celsius and 4 degrees Celsius by the end of the 21st century. “These predictions, combined with our regression estimates, imply that in the absence of any adaptation by farmers and any changes in policy (such as irrigation), farm incomes will be lower by around 12% on an average in the coming years, and unirrigated areas will be the most severely affected, with potential losses amounting to 18% of annual revenue,” the survey said.

The Indian government, therefore, intends to focus on improving irrigation in India. “Minimising susceptibility to climate change requires drastically extending irrigation via efficient drip and sprinkler technologies (realising ‘more crop for every drop’), and replacing un-targeted subsidies in power and fertiliser by direct income support,” the survey suggested.