The Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem commemorates the birth place of Jesus Christ. Imagine that a mosque was built on the spot during the Middle Ages. Now imagine that centuries after the building of the mosque, the Christians sued to recover possession of the site in the courts of a secular, Christian majority state.

Imagine that while the case was pending, the mosque was razed to the ground by a mob of riotous Christians and was not allowed to be rebuilt. Also, imagine a crib with the infant Jesus, standing under a makeshift tent continuing to stand on the site, protected from retaliatory damage by a huge amount of security.

Lastly, imagine that the court case has meandered on for a quarter-of-a-century after the demolition, as successive governments and generations of judges have preferred to avoid decisions one way or the other in the interest of maintaining domestic peace.

If you have imagined all this, you have essentially grasped the stakes before India’s supreme court, at a hearing scheduled to begin on Feb. 08 in the Ayodhya temple/mosque case. In the court’s previous hearing on Dec. 05, 2017, chief justice Dipak Misra referred to the Shavian preface—George Bernard Shaw’s habit of writing introductory essays for his plays.

“In fact a novel prayer was advanced that the matter should be listed some time in 2019. Dr (Rajeev) Dhavan, learned senior counsel almost thought of writing a Shavian preface, which can more than be main drama or a play, by stating that he would require four months to read, prepare, and argue,” Misra said, referring to the request by the lawyers on the Muslim side for a deferment of the hearing to a date beyond the general elections for India’s Parliament, currently scheduled to be held in mid-2019.

India’s Muslims are deeply anxious that a legal dispute with religious overtones should not be allowed to influence the outcome of the next general elections. The Hindu fundamentalist side believes it has a lot to gain with a speedy verdict that will, irrespective of its outcome, act as a catalyst for the consolidation of Hindu votes in a Hindu-majority country. Also, the fact that three senior advocates representing the Muslim side—Dhavan, Kapil Sibal, and Dushyant Dave, all practising Hindus—almost thought of withdrawing from the proceedings is in itself a major cause for caution.

Coming from a former teacher of English literature, the chief justice’s language indicated his exasperation with the submission that the court should not rush to judgment in a dispute that has profound political implications for the future of India.

The court’s order in December, shorn of legalese, deferred hearings to February 2018. While leaving open the possibility of a further deferment for administrative reasons, it has seemingly foreclosed the chances of the parties to the dispute seeking further deferral.

In a country where the law’s delay is more than proverbial, the request for a further postponement seems wholly unjustified—but only if you do not know the history of the case.

From mythology to politics

What, then, is the history of the Ayodhya case? How can a dispute over the title to a small plot of land in small-town India shake the very foundations of the republic? The supreme court is being asked to restore to India’s Hindu majority the possession of land on which a mosque stood for over 400 years prior to Dec. 06, 1992. If the court agrees, it is likely to be seen as having succumbed to majoritarian instincts bedeviling governance in the Indian subcontinent.

On the other hand, a rejection of the Hindu claim might appear to perpetuate a medieval-period Muslim injustice, wherein Mir Baqi, a general of the first Mughal emperor, Babar, allegedly built a mosque after destroying a temple commemorating the birthplace of Hindu god Ram.

A decision either way is likely to exacerbate communal tensions in a land riven by deep divisions. Whether there really existed a temple before the mosque was built is at the core of the controversy. A further question is if a wanton destruction 400 years ago can be avenged politically, or rectified through any legal process that would be constitutional, in a nation governed by the rule of law.

The most important political question, however, is: What kind of a republic is India? Is it to be a secular republic, treating all faiths equally? Or is it to be one where its majority Hindu faith is to be predominant in all public actions?

A brief retelling

A scanning of the facts set out in the legal briefs of both sides reveals that in 1857, the chief priest of the nearby Hanumangarhi temple took over the eastern part of the mosque courtyard. This is where the “Ram Chabutra”—a platform on the area alleged to be Ram’s birthplace—was built. Later that year, Maulvi Muhammad Asghar, the muezzin of the Babri Masjid, petitioned the local magistrate, complaining of a forcible takeover of the courtyard.

In 1885, mahant Raghubar Das filed a suit praying for a legal title to the land and for permission to construct a temple on the chabutra. He claimed to be the mahant (priest) of the janmasthan (birthplace) of Ram. Significantly, no claim that a temple ever stood at the spot where the mosque was built, was made at that stage. The suit was dismissed in 1886.

Shortly after India’s independence in 1947, idols of Ram appeared inside the mosque in 1949. On Jan. 16, 1950, a civil suit was filed by Gopal Singh Visharad (a member of the Hindu Mahasabha), asking for worship without obstruction and a perpetual injunction against the removal of the idols. A court ordered that the idols could not be removed. It also directed that the puja (worship) not be interfered with. The state of Uttar Pradesh filed an appeal against the injunction on April 24, 1950. In 1959, the Nirmohi Akhara, a monastic sect of Hindus, filed a suit praying that the entire mosque be handed over to it. Then, in 1961, came a suit claiming right over the mosque filed by the Sunni Central Waqf Board—the umbrella organisation of Sunni Muslim religious endowments. Besides the legal disputes, the period between 1951 and 1986 passed without any major incident.

Deadly balancing act

In 1985, prime minister Rajiv Gandhi had given in to Muslim fundamentalists in the Shah Bano affair. A supreme court judgment favouring of divorced Muslim women was overturned by parliamentary legislation. Gandhi’s opting to appease the Muslim orthodoxy left the Hindu mainstream uneasy. The latter was a constituency the Sangh Parivar was trying to consolidate. A few months later, the prime minister tried to restore the balance by giving the Hindus something, too.

An application to the Munsif (local magistrate) for the opening of the gates of the mosque had been filed by one Umesh Chandra Pandey in 1985 at the district headquarters in Faizabad. This was only five years after the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the political wing of the Sangh Parivar, had been floated. Interestingly, Pandey was not a party to the case at all.

An application to advance the hearing on Pandey’s plea was dismissed by the Munsif’s court. An appeal was filed before the district judge, who ordered that the locks on the Ramjanmabhoomi-Babri Masjid in Ayodhya be removed and left the question of law and order to be handled by the district magistrate and the state government of the day. The state government, in turn, received its instructions from the centre. The district magistrate and superintendent of police personally appeared before the Faizabad district court and stated that removing the lock from the main gate of the disputed structure would not create any law and order problem.

Until 1985, a priest had been permitted to perform puja once a year for the idols installed there in 1949. Now, all Hindus were seemingly given access to what the majority considered the birthplace of Lord Rama. In his memoirs, former president Pranab Mukherjee writes that the opening of the Ram Janmabhoomi temple in Ayodhya was an “error of judgment.”

Trail of blood

On Sept. 12, 1990, Lal Krishna Advani, the then president of the BJP announced a rath yatra (chariot procession) from the ancient temple of Somnath in Gujarat to Ayodhya. He sought to build a grand temple at the site of the mosque.

Led by Advani, the procession’s logistics were handled by the party’s then youthful general secretary Narendra Modi, today India’s prime minister.

Speeches accusing the union government of “appeasing the Muslim minority” and “denying Hindus of their legitimate” rights were made. Thousands of kar sevaks (people who volunteer their services for a religious cause) descended on Ayodhya. A pitched battle with the police and paramilitary forces ensued. At least 20 kar sevaks died. Their deaths were used to stoke religious tensions in Uttar Pradesh. Numerous riots followed.

In the 1991 election, the BJP had doubled its vote share to almost a quarter of the total votes cast, made inroads into southern India, and formed governments in four states in the north. Meanwhile, its sister organisations laid the groundwork towards the final assault on the Babri Masjid. In 1992, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, another right-wing Hindu nationalist organisation, announced that Dec. 06 had been chosen as the day for the work on the temple to commence. The temple would be built by kar sevaks from all over the country. Thousands poured in.

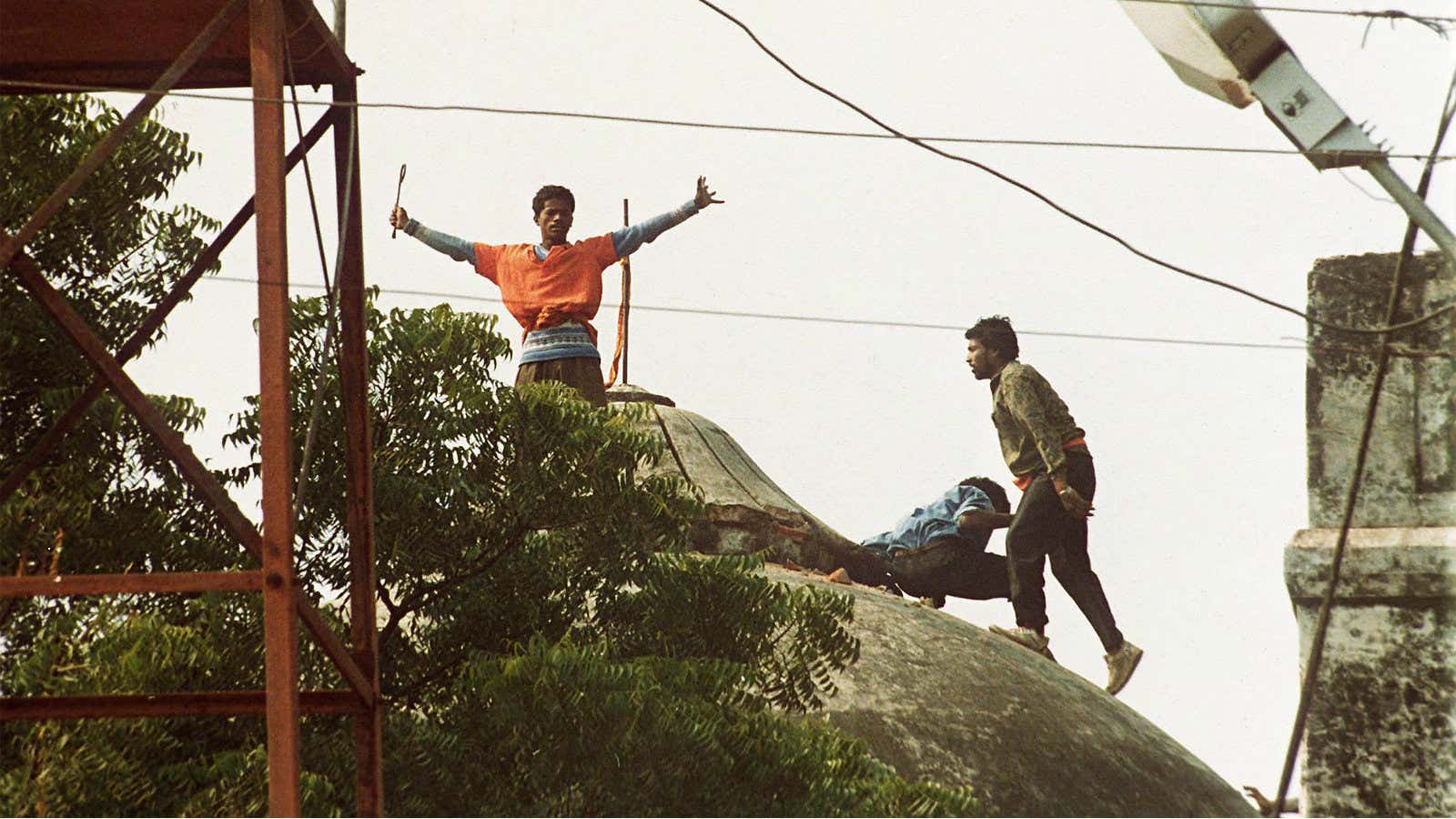

That morning, kar sevaks assembled to listen to fiery speeches from BJP leaders, including Advani, Murali Manohar Joshi, and Uma Bharati. The first attack on the mosque was mounted around noon, with kar sevaks climbing onto the domes of the mosque. Outnumbered by the mob, the local police fled. By 5PM, the mosque had been reduced to rubble. A makeshift temple with the idol of Ram was installed at the spot. To this day, the unfinished temple, with an idol under a makeshift roof, stands.

It was thought that an act of such vandalism in a democracy bound by the rule of law would not be condoned. The current attorney general for India, KK Venugopal, then appearing as a senior advocate for the state of Uttar Pradesh on that day at an emergency sitting of the supreme court, submitted: “My head hangs in shame.”

The Kalyan Singh government in Uttar Pradesh was subsequently dismissed and president’s rule was imposed. The deed had, however, been done. Soon after the demolition, the union government promulgated a law to acquire the disputed areas. This was challenged in the supreme court.

At the same time, a presidential reference—a constitutional provision under which the president of India can request the supreme court to provide its advice on certain matters—was also made. Among other questions, the reference queried the court: “Whether a Hindu temple or any Hindu religious structure existed prior to the construction of the Ram Janma Bhumi-Babri Masjid (including the premises of the inner and outer courtyards of such structure) in the area on which the structure stood?”

The slow turning of gears

In its 1994 judgment in Ismail Farooqui’s case, the supreme court by a majority of 3:2 upheld the validity of the law providing for the state’s acquisition of land in the Ram Janma Bhoomi-Babri Masjid Complex. The presidential reference was, however, returned unanswered by the court, which declined to answer it for various reasons.

Justice SP Bharucha noted, “Ayodhya is a storm that will pass. The dignity and honour of the supreme court cannot be compromised because of it.”

In the supreme court’s ruling of 1994, the civil suits (from the 1950s and 1960s) based on title were revived and sent back to the Allahabad high court for adjudication, with directions that the status quo as of Jan. 07, 1993, be maintained. This meant that the makeshift temple erected on the disputed site after Dec. 06, 1992, would remain.

In September 2010, the Allahabad high court delivered its verdict in the Ayodhya title suit. The bench declared that there would be a three-way division of the land between the Sunni Waqf Board, the Nirmohi Akhara, and the guardian of the deity “Ram Lalla.”

As expected, the verdict didn’t satisfy either party, and appeals were filed before the supreme court.

In 2011, the supreme court clarified its status quo orders, stating that in “the 67.703 acres of acquired land located in various plots detailed in the Schedule to Acquisition or Central Area at Ayodhya Act, 1993, which is vested in the Central Government, no religious activity of any kind by anyone either symbolic or actual including bhumi puja or shila puja, shall be permitted or allowed to take place.”

Final act

In 2014, Modi was sworn in as prime minister.

Amongst members of the ruling dispensation, the demolition of the Babri Masjid is seen more as an assertion of the legitimate rights of Hindus, rather than as an instance of the total breakdown of the rule of law. The building of a grand temple in Ayodhya at the very spot that the mosque once stood is now seen as only a matter of time by supporters of the ruling dispensation.

The case in the supreme court is seen as an unnecessary impediment to be overcome by a judicial verdict or by a parliamentary law. If there is seen to be no definite movement towards the construction of the temple, it would be taken as a breach of political faith on the part of the Hindu nationalist BJP.

In March 2017, BJP member of parliament Subramanian Swamy (who was not originally a party to the Ayodhya dispute) intervened in the appeals pending before the supreme court, and asked for an early hearing. The application for the opening of the gates of the mosque (that ultimately led to the events of 1992) was also made by a stranger to the proceedings.

Swamy’s original plea for an early hearing was rejected by the court. However, in July 2017, the court agreed to list the appeals for hearing. After various administrative delays, the matter came to be listed on Dec. 5, 2017, a day before the 25th anniversary of the demolition.

The bench hearing the appeals is headed by chief justice Misra. He is to retire in October 2018 and would have to adjudicate the appeals before retirement. Should the judgment indeed be delivered before October 2018, it would come only months before the 2019 general election. Whichever way the court decides, the judgment will introduce an emotive religious issue that is likely to be used by the ruling party and the opposition to gloss over issues related to governance and the economy.

If the title is vested in the Hindu side, it may well be seen as another instance of an organ of state succumbing to majoritarianism. If the title is vested in the Muslim side, it is unlikely that the mosque can be rebuilt without major repercussions on the ground.

All told, a final judicial verdict either way will not result in a solution, but is more likely to exacerbate existing fissures in a multicultural society.

And what is more likely to suffer is the reliance upon and adherence to the rule of law.

This then is the Shavian preface to the request for a deferment of the case beyond May 2019. The request having seemingly been refused, the stage is set for the final act. India’s moment of self-recognition awaits.

We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.