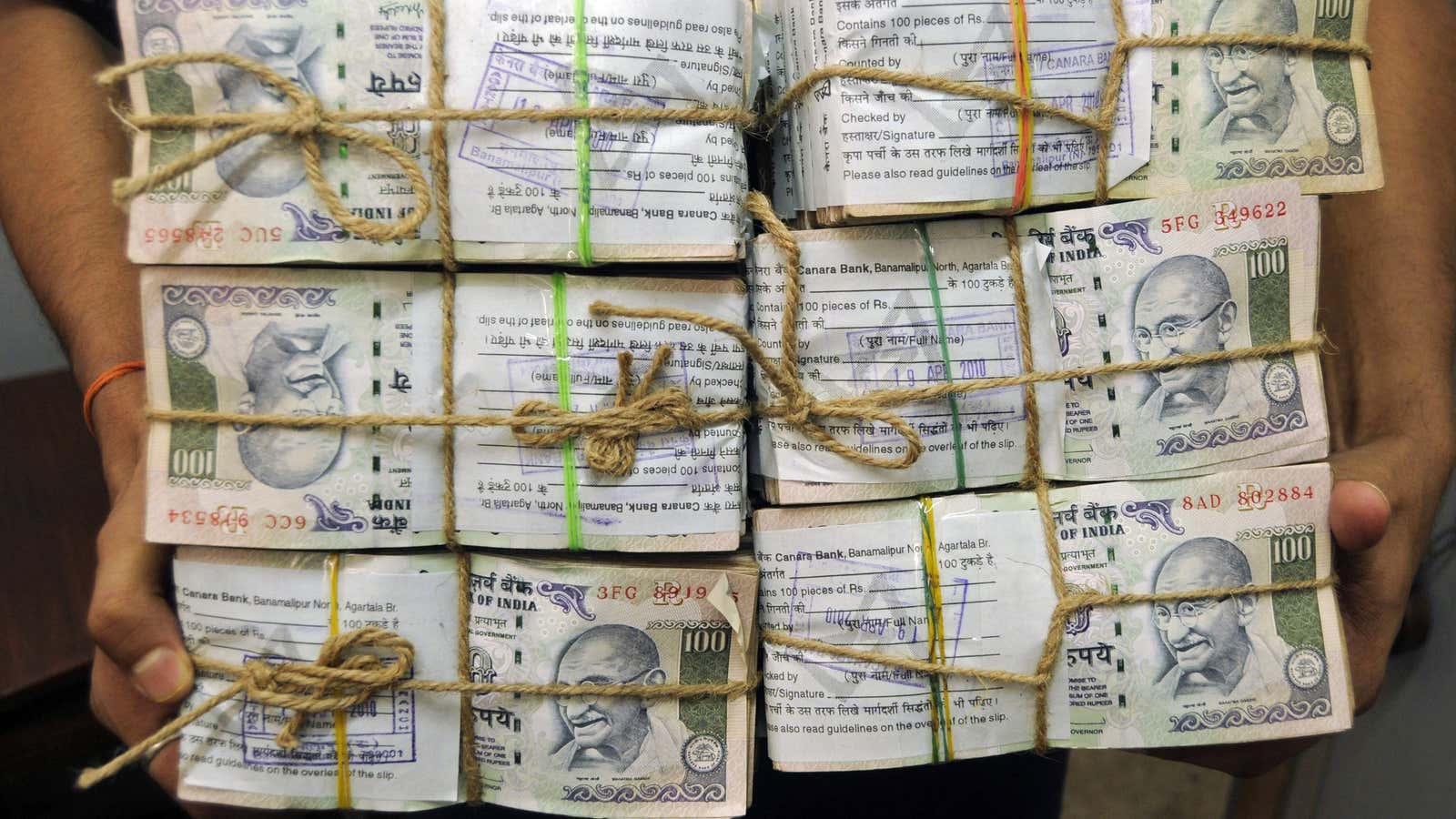

Indian banks have restructured over Rs6 lakh crore (over $93 billion) in bad loans in the last three years, and unearthed over $1.8 billion of fraud in the last three weeks. And if you thought it couldn’t get worse, here’s more.

Nearly 30% of all bad loans in India may not be recovered—ever.

“By my reckoning, the amount that will be irretrievably lost, will be probably around Rs3 lakh crore and not more than that. The remaining may be retrievable, which means banks, and promoters have to take haircuts,” Bibek Debroy, chief of prime minister Narendra Modi’s economic advisory council, told Quartz during an interview.

Coming after the massive write-offs of the last three years, Rs3 lakh crore more in write-offs could deal a knock-out blow for India’s fragile banking system struggling with insufficient capital, tepid credit growth, and a surfeit of bad loans.

With about Rs10 lakh crore in non-performing assets (NPA), India was ranked fifth among 39 major economies for the most bad loans by Care Ratings in December 2017. Nearly 88% of this toxic pile belongs to state-run banks.

Debroy, though, sees a silver lining.

“I don’t think the stress is spread uniformly across all banks, or uniformly across sectors or companies. I would say (the same) about just public sector banks, too,” he said.

Meanwhile, the Modi government had announced a Rs2.11 lakh crore recapitalisation plan for state-owned banks. With a string of frauds uncovered in the past few weeks, should it now wait before pumping in more money? “Recapitalisation is required in any case. There is already a stock of NPAs and banks need money. The recapitalisation package is required to trigger reforms at PSU (public sector undertaking) banks,” Debroy said.

About privatisation

There is a growing clamour for the privatisation of government banks. Proponents of such a move include chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian, industry lobby Assocham, and industrialist Adi Godrej, among many others.

Debroy, however, feels “people are being too simplistic.”

The first source of his apprehension is the inherent weaknesses of India’s government banks. “Will you buy ‘x’ bank with the current assets and liabilities? The answer is probably ‘no.’ It will be cheaper for you set up a new bank. I don’t think there will be any takers. Not until there has been some cleaning up,” Debroy said.

Besides, as pointed out by finance minister Arun Jaitley on Saturday (Feb.24), the government runs the risk of losing political capital in trying to reverse the nationalisation of banks. Therefore, Debroy suggests a staggered approach.

“I am not talking on behalf of the government now. I am inclined to think that the route we are talking about is to move some banks to the Companies Act and then you (the government) can dilute the equity,” suggested Debroy.

Currently, all public sector banks are governed by the Bank Nationalisation Act, introduced by then prime minister Indira Gandhi in 1969. It has been perceived as a hugely popular move since then and any move to reverse it could potentially evoke people’s ire.

“If you are not doing it (bank privatisaion) across the board, then I don’t see a great problem. If you try to do it for all banks, then its the rollback of the Bank Nationalisation Act. That will lead to all kinds of things,” he added.

In the meantime, especially in the wake of the most recent frauds, the clamour among investors and taxpayers for more reforms and accountability has only grown. Despite more and more evidence emerging of gaping holes in their governance, there have been no management changes at any of the banks.

Their proposed privatisation has been ruled out and, as Debroy suggets, the government will only continue to invest more taxpayer funds in them.

In short, it’s business as usual, when it shouldn’t be.