In 1776, an entrepreneurial Irishman who had come to India to make his fortune ended up in the horrifying squalour of an 18th century Calcutta prison.

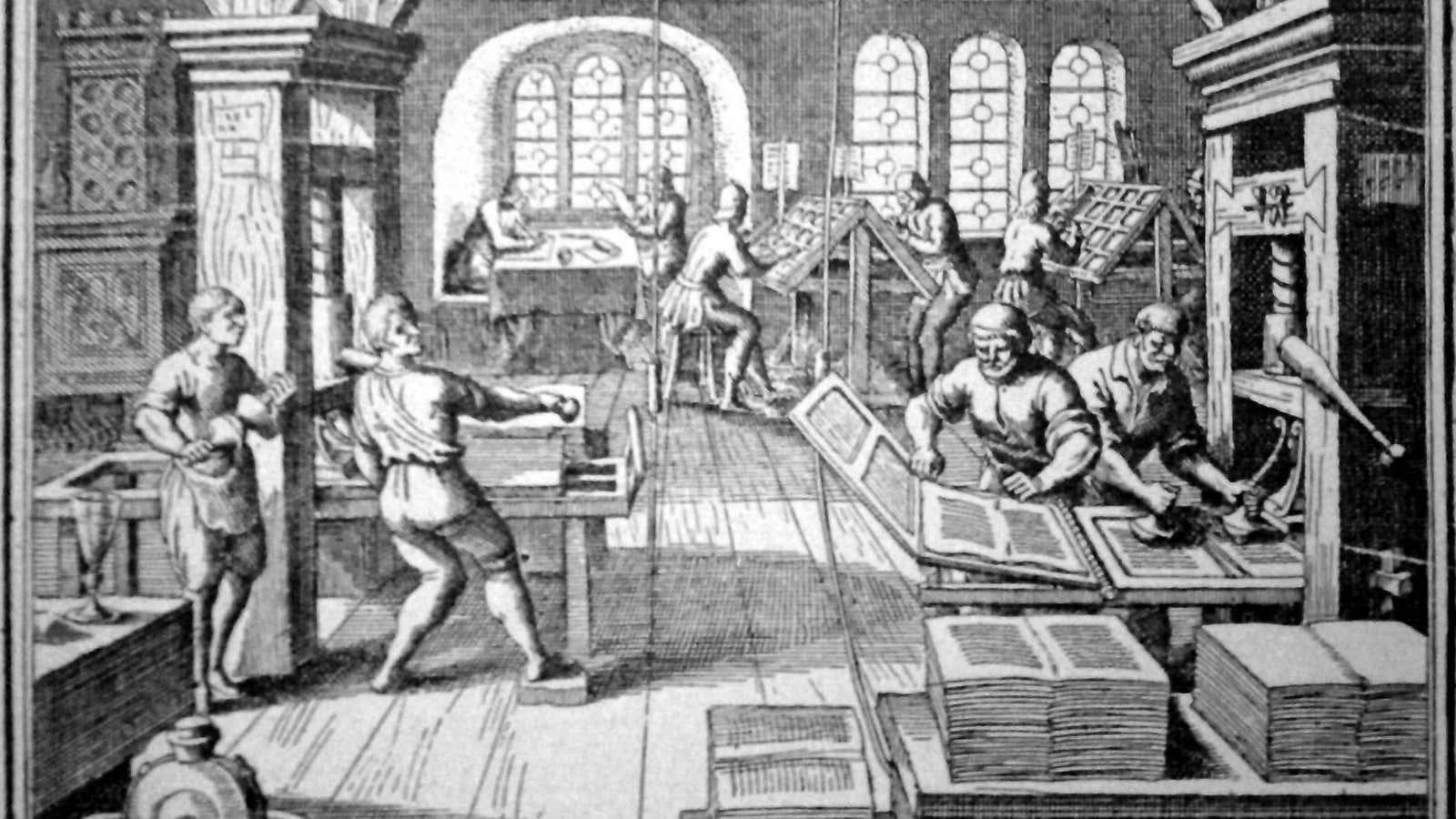

A one-time surgeon whose attempt to launch a shipping business in the city had gone wrong, James Augustus Hicky had been labelled a debtor and forced to go to jail as bankers seized all his belongings. But they didn’t quite get everything: Hicky was a smart one, and he had squirreled away Rs2,000 with a trusted friend, which he later used to order types and pay carpenters to construct a printing press for him. While still stuck in jail, Hicky embarked on his newest venture, working from six in the morning till one or two at night, printing handbills and advertisements to make a little more money.

A few years after he was finally released from prison, printing would go on to become Hicky’s most successful and controversial business when he decided to start publishing India’s first newspaper.

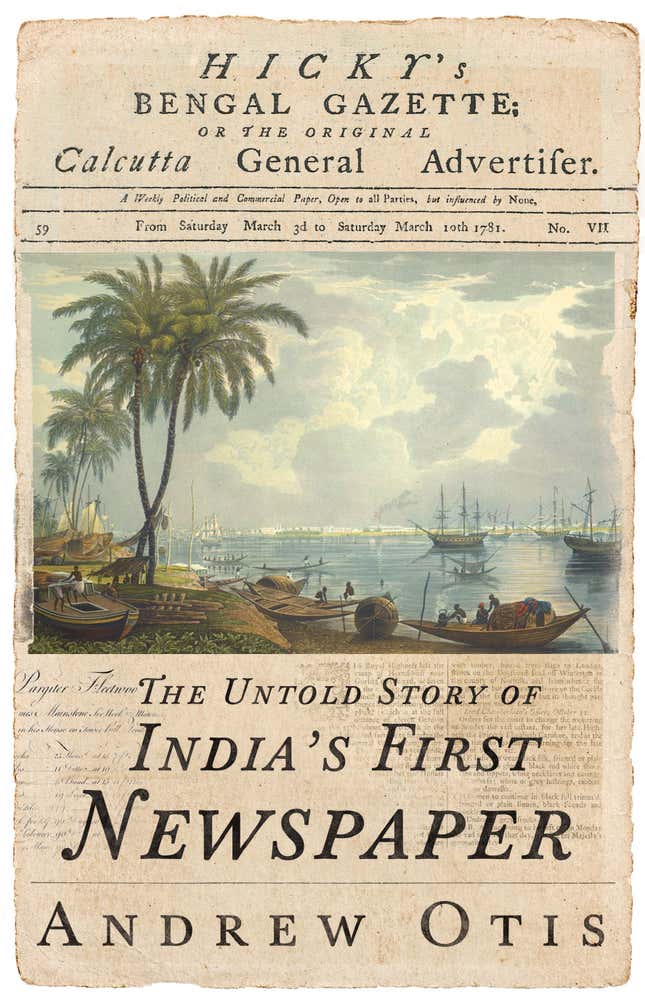

In Hicky’s Bengal Gazette (Westland Books), American researcher Andrew Otis dives into the lively history behind this pioneering paper, which started out at a time when Indians mostly got their news through word-of-mouth, while Europeans living in the region relied on outdated newspapers that were brought over by ship.

Using diaries, letters, and other documents found through years of research in the dusty and largely disorganised archives of India, besides Germany and the UK, Otis pieced together the story behind Hicky and his newspaper. While it’s not the first book about the man and his mission—Indian academics P Thankappan Nair and Tarun Kumar Mukhopadhyay have also written about him—Otis says he found much more material that adds to the story.

“Hicky had an extraordinary life…He was a risk-taker,” Otis told Quartz in an email.

Hicky put out his first issue of the Bengal Gazette on Jan. 20, 1780 after promising to revolutionise news in India, besides offering neutrality and a “rigid adherence to Truth and Facts.”

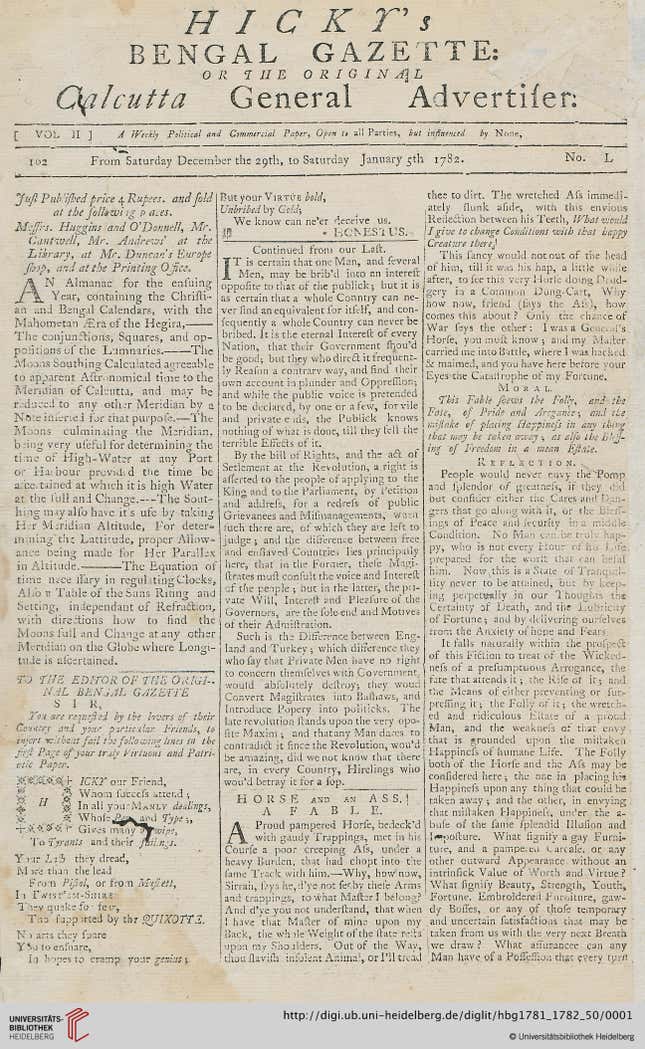

Otis writes that the newspaper was immediately a sensation. Over the following months, Hicky and his correspondents made the paper a must-read, publishing pieces about everything from Indian events to world news, and encouraged readers to submit letters and poems. Hicky took up issues of local interest, urging the British East India Company (EIC) to invest in bettering Calcutta’s (now Kolkata) sub-par infrastructure, roads, and sanitation.

As time went by, he became increasingly interested in the lives of the less privileged in Calcutta. Otis writes:

Hicky covered news that others might have passed over. He did not write solely about Europeans, but discussed the tragedies and happinesses of both European and Bengali poor. For example, he reported a miraculous story of how one woman survived to give birth amid a great fire. He covered the demise of a palm sap picker who fell to his death from a coconut tree. He reported boats that overturned in the Hooghly and the commoners who drowned. He reported the violence of British sailors who seized men in punch houses to force them into the navy. In bringing stories like these to light, he saw himself as servant to society, covering topics of which many would have been ignorant.

Hicky’s newspaper also covered the various wars Britain was fighting at the time, and as the only one in the region it became an essential source of information for the British, American, and even French newspapers, according to Otis.

But given the context of 18th century Calcutta under EIC rule, Hicky’s newspaper couldn’t stay truly neutral for long. The extent of corruption in the city was staggering, and embezzlement and nepotism were rampant. After a rival paper was set up in November 1780 with support from the EIC, and allowed to post its copies for free, Hicky started to believe his newspaper was being punished because he refused to pay a bribe early on. And that prompted him to come out guns blazing in an article that savagely exposed the alleged corruption of the man involved, the incredibly important and influential chief of the board of trade. As punishment, the governor-general of British India, Warren Hastings, ordered that Hicky’s newspaper would not be allowed to be sent out to subscribers through the post office.

It was a big blow, but it marked the beginning of Hicky’s war against the EIC in print.

“The next week, he started an anti-tyranny, anti-corruption, and pro-free speech campaign using his newspaper as his platform, and words as his weapons,” Otis writes.

Besides savagely attacking the corruption of the EIC’s employees in India, Hicky also exposed the shady dealings of the influential and greedy Christian missionary Johann Zacharias Kiernander. But his incendiary articles prompted both men to sue, and in June 1781, Hicky was taken to court on five counts of libel and thrown into jail with an impossibly high bail.

Hicky faced four trials and continued to print his newspaper throughout, accusing the EIC of trying to stomp on his freedom of speech. He was eventually sentenced to 12 months in prison and ordered to pay a fine of Rs2,500. In 1782, left with almost no money, Hicky filed to be recognised as a pauper so that he could at least keep his type and printing press, but after initially saying yes, the court reversed its decision and they were seized, bringing to an end the short run of the Bengal Gazette.

Though Hicky would eventually be released, he was left with nothing, desperate for money to feed his family. It’s not known how, several years later, he ended up on a ship to China, but that was where he died in 1802.

Hicky’s life’s work wasn’t for nothing, though. Because of his reporting, the crimes of Hastings and the chief justice, Elijah Impey, were made known to the world, Otis says. The two men were recalled to England and unceremoniously impeached. As a result, Hicky’s legacy shows him as an unlikely pioneer of freedom of speech, and is a timely reminder of the essential role of the free press.

“Hicky is important because one of the most fundamental rights in democracy is the right to criticise your rulers,” Otis said. “Hicky said that he had the power to print a newspaper that no man, nor any king, had the right to take (that) away from him. This is a useful lesson, especially today.”

This post was corrected to fix the name of the British governer-general, Warren Hastings.