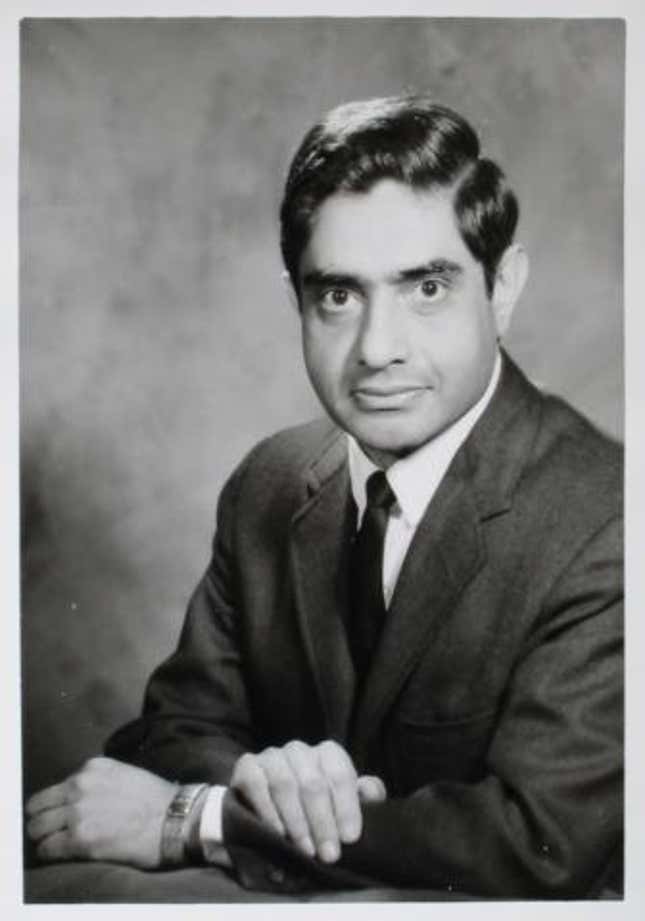

On Aug. 25, 1949, Roshan Sharma got his first glimpse of the Golden Gate Bridge as the SS President Wilson approached San Francisco, California. The 22-year-old from Bhumbli in Punjab had braved a long, uncomfortable journey on the ship from Hong Kong, subsisting on the only vegetarian food available: boiled rice, potatoes, and fruit.

After getting off the ship, a famished Sharma found himself stuck in a long line at the customs-clearance hall. So when an American he had befriended on the ship brought over a sandwich, he simply devoured it. Only after finishing it clean did Sharma enquire about the meal he’d just had: a beef hamburger.

“The sudden realization made the earth disappear from under me. The thought of a Brahmin boy eating of the holy cow tore me apart. According to the Hindu code book, I had committed the greatest sin of all,” Sharma recalled decades later. On seeing himself surrounded by “tall, healthy, and vigorous” beef-eating Americans, though, he decided to let it slide.

The memory of that first day on American soil never faded away. In the decades since then, hundreds of thousands of south Asians have landed in the US. And many of them have an anecdote or two that marked their first day there.

Sharma’s is just one of the over 400 stories gathered by the First Days Project, an initiative of the non-profit South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA). Since 2013, the organisation has been collecting the memories of immigrants and refugees from around the world, specifically focusing on who they met and what they saw, ate, and did in their first days in the US. These are things they often remember vividly, no matter how many decades have passed, according to Samip Mallick, SAADA’s executive director.

The goal, he explained, is to record the “human experience of migration”—what it’s like to arrive in a new place, leaving behind friends and family and everything that is familiar—which is often left out of the conversation about life in the US.

“The stories of what it’s like for immigrants to arrive in this country, what their experiences are like on their first days, don’t get told,” Mallick said.

Among the many stories SAADA has collected are 131 accounts from people of Indian origin, beginning with Sharma’s journey in 1949 and going up to 2015. The collection covers immigrants from all over India, those who moved for education and work, both men and women. Some have been gathered by SAADA volunteers, while others are uploaded onto the site directly by members of the Indian-American community who interviewed their parents and grand-parents.

The earliest accounts date from a time when Indians made the long journey to the US by ship, and encountered a culture completely alien to their own. Besides their anticipation and anxiety over moving and managing money, there are also delightful stories of tasting hot dogs and pizza and seeing snow for the first time. Some immigrants are shocked by the number of cars on the roads, while others are flummoxed by how hard it is to find basic Indian ingredients.

One thing that’s common to many of the early accounts is having to depend on complete strangers for help. For instance, CM Naim, who migrated to California from Barabanki, Uttar Pradesh, in 1957, recalled bursting into tears at the airport after losing a suitcase that contained his degrees, passport, and the only American money he had at the time: $25. But an elderly African-American man came to his rescue, and after a few hours he helped track down the bag which had been carried off to a hotel by an unsuspecting fellow passenger.

“From the 1960s and 1970s onwards, when people were landing in the US, obviously there’s no cellphones, there’s no internet at that time… Very often the story that comes up is whoever’s supposed to meet them (at the airport) didn’t show up. And so what they do and how they figure out where they need to go, how they need to rely on the kindness of strangers, those are kind of the stories that you hear so often,” Mallick said.

In the 1950s and 1960s, many Indian immigrants also had to contend with America’s racist policy of segregation. BP Rao, who moved from Hyderabad to study at Virginia Tech in 1959, recalled how a trip to the men’s room in Indianapolis opened his eyes to the discrimination that non-white communities faced in the US.

I wanted to go to the men’s room—then I noticed that there were black and white restrooms. I knew there was discrimination, but I didn’t know which restroom I should go to. It was sort of puzzling—I didn’t know what to do. So I said, ‘Okay, let me go into the white men’s room and see what happens.’ Nothing happened, but they were all looking at me. The white people probably thought I looked strange. That was the first encounter where I realized there was discrimination… Before I came to America I thought anybody can do whatever they want to. It’s a free society.

Lakshmi Jayaraman, who migrated from Calcutta (now Kolkata) to the US in 1960, briefly lived in Florida when segregation was in full-swing. “In the gardens, anywhere you sit, it would be written, ‘whites only, blacks only.’ That made me feel very bad,” she recalled in an interview with her grand-daughter.

Migrant matters

Beyond Indians, the First Days Project also has accounts from people from Pakistan, China, the Philippines, and Mexico, all of whom have similar experiences of learning to adapt to a new way of life in a new country.

Though the project began a few years ago, the intensifying anti-immigrant sentiment in the US makes these accounts all the more poignant today. In the wake of the IT boom that sparked a new wave of migration from India, immigrants have been accused of stealing American jobs, and the H-1B visa, which allows foreigners to live and work in the US for up to six years, is in the eye of the storm. The brutal “zero tolerance” policy imposed by the Donald Trump administration against illegal immigrants has affected countless families, including a number from south Asia.

“Particularly in this moment when there’s so much debate over the role of immigrants and immigrant contributions to American society, hearing stories from immigrants and refugees in their own words seems incredibly important,” Mallick said.