Marine Le Pen was making hate speeches in the run up to the French election and Kim Jong Un’s estranged half-brother had just been murdered in a spy fiction-esque assassination in Kuala Lumpur. Scrolling through the news feed, I waited for the tea to arrive before Nandita Das first narrated the part of Shyam Chaddha to me. It was the week a Yogi had been sworn in as chief minister of Uttar Pradesh and Donald Trump declared his first travel ban that Nandita was casting for her period biopic, Manto.

The only semblance of order at the time came from American late night stand-up whose parody-laced narrative made fascist rhetoric palatable. It seemed like a world of alternate facts was spinning out of control, countered only by a barrage of thoughts and prayers.

Our tea arrived in the midst of the news feed and I was informed that Nandita was looking for her Shyam. What struck me about my chats with Nandita was how she spoke of the film’s characters like they were still alive. Shyam, as I would learn through the course of the weeks after that first meeting, was the 1940s Bollywood star whose flirtation with Bombay’s (now Mumbai) bylanes led him to cross paths with the Urdu literary maverick Saadat Hassan Manto.

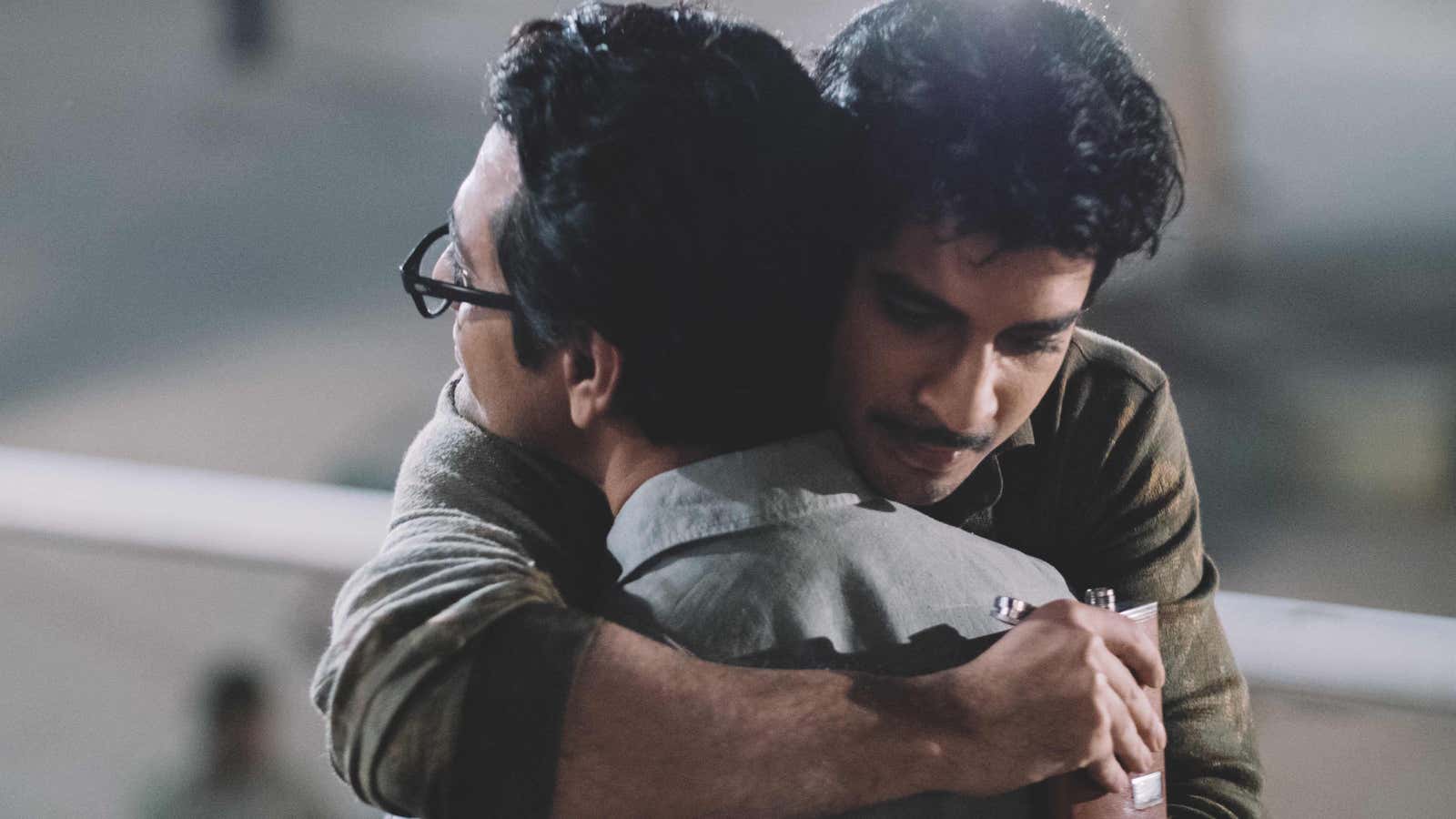

Their friendship began with conversations at a staircase of the High Nest building on Lady Jamshedji Road in Mumbai and thereafter grew into an inseparable camaraderie.

At first glance, Manto and Shyam were chalk and cheese—one an introverted intellectual, the other a boisterous charmer out to make his way to the big screen. On closer inspection it was evident that their irrepressible desire to poke a finger in the eye of the establishment was their connect. The duo even had a term for anything that was out of the ordinary, they called it their “Hiptulla.”

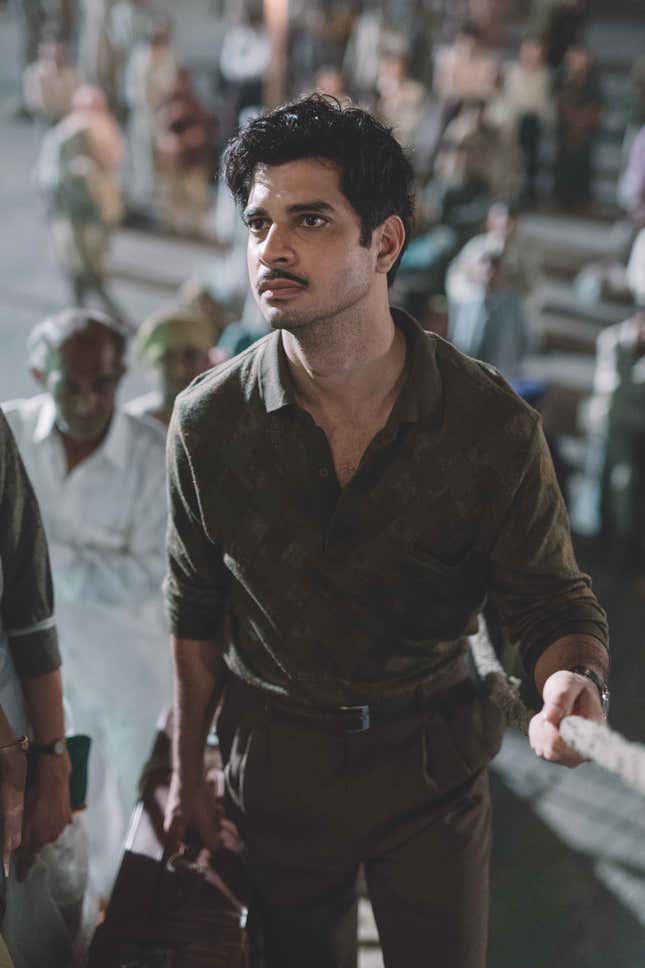

On the sets of the movie Manto, I found that one of the challenges of embodying real-life stories is the mixed medium of facts and imagination, and how one’s collage of experiences colour ones representation on celluloid. A fascinating canvas to work off while re-sculpting Shyam was the philosophical banter and interminable drinking sessions he shared with Manto, sketched by the latter in Murli Ki Dhun, arguably one of the most moving chapters in his book Stars from Another Sky.

Shyam like many actors who first move to Bombay, then and now, dealt with his share of resistance from his working-class family. In his friendship with Manto, perhaps, he found acceptance—a fellow rebel and a creative mentor. In the early years of their friendship, when Shyam was between debt, dating, and screen tests, Manto was a force to reckon with at Bombay Talkies, hobnobbing with Ashok Kumar, K Asif, Naushad, and other icons in an industry where Shyam was destined to rise. To the world he was a maestro but to Shyam, Manto was a brother and a drinking buddy who shared an abhorrence for societal conformity, a philosopher to his chariot. Manto once described Shyam as someone who reminded him of a character from a Russian novel, an intense lover whose greatest weakness and strength were the string of women he dated until he married his one true great weakness, the actress Taji (Mumtaz).

As I soon discovered, rummaging through archives of letters and conversations between the duo, this was not just a writer and an actor. These were counter-culture rebels in search of experiences that would enrich existence. In millennial speak, a cross-breed of hipster outliers who relished the finer things in life. As Shyam put it in one of the many letters he wrote to Manto, “I am not of a given place and do not wish to be of a given place. Come to think of it, life is my one and only sweetheart. As for people, they can go to hell.”

Over the graph of Manto’s pre- and post-partition literary work, Shyam was propelled from being the aspiring actor to box-office gold. He broke through in 1949 with successful films where he worked with leading actresses of the day, including Chandni Raat (Naseem Banu), Patanga, and Bazar (both Nigar Sultana), Char Din and Naach (Suraiya), Meena Bazar (Nargis), and his most popular release, Dillagi.

His moment of stardom, however, revealed itself much before consciousness was veiled in Instagram stories and, as a result, few records of his meteoric rise and sudden death (in a horse-riding stunt) funneled down pop culture archives. He was working on two films, Kale Badal and Shabistan, at the time of his demise.

Shyam, the star, left behind a hazy imprint on the fickle memory of Indian film history. For movie buffs from my grandparents’ generation, however, a mention of his name still lights up their eyes before they hum Tu mera chand, mein teri chandni, the hit song from Dillagi. Although he passed away at the peak of his career, many old-timers are convinced that had Shyam survived, he would have given Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand, and Raj Kapoor—the triumvirate of the 1950s—a solid run for their money.

It was now, as a result of his close friendship with Manto, that I was getting a retrospective into history’s creative cowboys and their time in the face of religious and creative intolerance. Acting in 2018 with Nawazuddin Siddiqui only added to the metaphysical appeal that flashed through my mind in that first meeting with Nandita. Trying to capture that chemistry between an aspiring actor and an iconic writer from half a century ago with a present-day actor early in his career and a star with a cult following, had a romantic art-imitating-life ring to it. Actors playing artistes wanting to work in film, in a film, made for a fascinating kaleidoscope.

At one of our shoot locations for Manto, Nawaz and I sat in make-shift green rooms behind the single screen of Edward theatre in Kalbadevi, Mumbai. With its pastel blue interiors, white and gold trimmings, and the three tiers of seating, the theatre was a sort of hidden gem that had slipped through the cracks with a musty stench of displaced harmony between a past living in the present. Before we got to rehearsing the scene, our conversation that evening fluctuated between career advice, films, and censorship. In those brief moments of time, reel fused with real as we shuttled between the prism of 1948 and 2018, dressed for one, captive by the other, characters at once in our own stories and the ones we were telling.

Often when we’d get dressed in vintage costumes and hair pieces on our set, I’d muse what Manto and Shyam might have said about today’s times—the politics of religion, the intolerance, and the censorship. All as familiar in our streams as they were Manto’s prose.

Would Manto be a supporter of the digitisation of art and the proliferation of publication, creativity, and the consumer or would he have been a staunch critic of its simultaneous dilution of impact and its nano-second hold on human conscience. What would the hashtag have meant to an influencer from the 1940s who braved a time when his words and their visuals had a lingering impact, for they sought to open one’s eyes to reality rather than escape it. Would these retro rebels we dressed up as on set believe that these wars for creative liberty were fought to date on cyber-battlegrounds where everyone’s a judge and everyone a defendant.

By the time I finished the tea at the meeting with Nandita where I first heard about Manto and Shyam, I wondered what an artistic act of irreverence might look like today.

Perhaps a way to transcend superficial hashtags of trending activism was to be a part of a massive throwback of retro rebellion with the common filters of sexuality, censorship, and religion that were dealt with on an alternate timeline by a man who dared to counter populism and just say it like it is.

We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.