As the Indian supreme court releases its judgment on the world’s largest biometric identity programme tomorrow (Sept. 26), one widespread practice involving Aadhaar may specifically be addressed: its use as a photo identification card.

In the near-decade since the programme’s inception in 2009, Aadhaar has enrolled over 1.22 billion people: about 90% of India’s population, and the vast majority of its adults. The enrollment has been fuelled, in part, by the government’s aggressive push to make Aadhaar mandatory for many services, including filing income tax returns and obtaining mobile SIMs.

In all this, Aadhaar has also come to be one of the most commonly accepted photo IDs in the country. Government officials often require people to show them before taking exams or as part of official applications. Many private companies, from delivery services to digital lenders, ask customers to show their Aadhaar cards or submit scans of them. Even airports, which mandate people entering the building to show an air ticket and photo ID, allow passengers to flash their Aadhaar cards for this purpose.

There are many problems with this.

Most fundamentally, Aadhaar was not designed to be a photo ID system. Because of this, it is not built with the robust security features that good photo IDs should have that make them difficult to reproduce. The issue occupies a legal grey area as well: The Aadhaar Act, passed in 2016 to provide legal backing to the programme, does not discuss the Aadhaar “card.” In fact, the Unique Identification Authority of India, the body that administers the programme, has always maintained that there is no particular value to the card other than the number itself.

Aadhaar is a biometric identity system. Verifying an individual’s identity through it involves authentication, whereby a person’s Aadhaar number, along with another data point—either a biometric marker like a fingerprint or iris scan or a one-time password sent to their registered mobile number—is digitally queried against a central database. If the inputs match with an entry in the database, the authentication returns a “yes” response and the person is judged to be who the Aadhaar says he or she is.

When Aadhaar is used as a photo ID, however, no authentication is generally performed. This, critics argue, defeats the very purpose of introducing a biometric ID.

“Aadhaar was brought in on the grounds that existing forms of ID are easy to fake,” said Gautam Bhatia, a lawyer for the petitioners in the constitutional challenge to Aadhaar. “What makes Aadhaar different from other IDs is authentication. So if you remove authentication, then Aadhaar is no longer any different from any other photo ID. So there is no point.”

Let’s (not) get physical

Many factors make the Aadhaar card vulnerable to forgery.

First, it lacks the security features that make other IDs more difficult to reproduce, such as a hologram, official seal, or microchip. “Without any of those features, you can’t use it as a physical ID,” said Srinivas Kodali, a security researcher who has done extensive work on Aadhaar. “So what’s happening here is that you have designed a digital identification system which you want to verify physically and that’s not happening because you haven’t designed it for physical use.”

What makes matters worse is that there is supposed to be no meaningful distinction made between the validity of an Aadhaar’s original copy—often referred to as the “Aadhaar card”—versus an “e-Aadhaar” that one can print online, as many times as they want, through the UIDAI’s website. While this may make sense when paired with authentication, it only makes Aadhaar documents easier to fake when they are to be visually inspected.

Weaknesses in Aadhaar’s security are compounded by the ID’s power.

Aadhaar is officially considered a valid proof of address, unlike some other IDs, such as the PAN card, which is required for filing income taxes (and which also, incidentally, has an official government hologram).

Kiran Jonnalagada, co-founder of the Internet Freedom Foundation, said that while a PAN card is “not that dangerous” because it does not qualify as an address proof, “a passport is a little more dangerous because it is also an address proof and you can go and apply for a lot of services using just a passport copy. And therefore you will find that a lot of service providers, when they accept a passport copy, will also require their officer to see the original and basically attest that they have seen the original and accepted the copy.”

With Aadhaar, which counts as address proof and also tries to draw no distinction between the original and printouts, Jonnalagada said, the system is even more vulnerable to fraud.

Many websites and apps provide a template for people to make fake Aadhaar documents. People with graphic-design skills can cobble them together on software like Photoshop with ease.

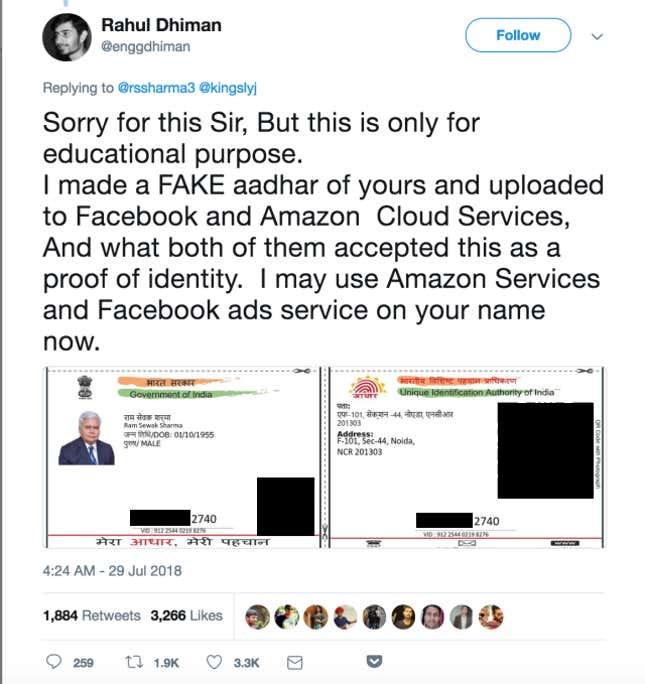

In fact, when RS Sharma, chairman of India’s telecom regulator and the first director general of the UIDAI, tried to prove a point by tweeting his Aadhaar number and challenging others to harm him, one obliging individual found his demographic information, which was publicly available online, and forged an Aadhaar card that Amazon Cloud Services and Facebook supposedly accepted as genuine.

People were able to harm Sharma in other ways too, including reportedly recovering his frequent-flyer number, which was believed to be one of his Gmail password-recovery questions. The UIDAI attempted damage-control after the incident, asking people to “refrain from publicly putting their Aadhaar numbers on the internet.”

Aadhaar-related financial fraud has been extensively reported as well, with many instances in a list of over 100 such cases involving the creation of fake Aadhaars.

Another major problem is that many entities, public and private, ask people to submit photocopies or scans of their Aadhaar card. These images are often stored in digitally insecure ways, which has led to many instances of people’s Aadhaar document scans being made publicly accessible on the internet.

“These days, Aadhaar is being scanned, and also being leaked,” said Srikanth Lakshmanan, founder of Cashless Consumer, an education initiative on digital payments. “There is no way for you to actually control how far that paper has reached and how many copies are being made out of that paper.”

Mixed messages

The FAQ section of the UIDAI’s website gestures at how common using Aadhaar as a photo ID is: “There are many agencies that simply accept (a) physical copy of Aadhaar and do not carry out any biometric or OTP authentication or verification. Is this a good practice?” one question reads. The UIDAI’s answer confirms that this practice is not recommended, and that Aadhaar should only be considered identity proof after authentication. “If any agency does not follow these best practices, then that agency will be fully responsible for situations or losses arising out of possible misuse or impersonation,” it says.

In practice, however, the UIDAI has not taken pains to discourage institutions from treating Aadhaar as a photo ID.

In fact, the first UIDAI chairman, former Infosys CEO Nandan Nilekani, has spoken in favour of using the document as such. “I use it all the time as a photo ID,” he said in an interview with Quartz last year. “The thing is that it’s also about convenience, right? See privacy and convenience go hand in hand. All of us give up a bit of privacy for convenience.”

Nilekani has not been a part of the UIDAI since 2014, but remains the most recognisable face associated with the programme and continues to talk about it to the media and otherwise.

Queries sent to the UIDAI did not receive a response.

Even though the authority and other top government officials have tried to emphasise that Aadhaar is a number, not a card, confusion on this point lingers. For example, a few months ago reports surfaced that some students in Maharashtra were prevented from taking the law entrance exam because officiators were only accepting “original Aadhaar cards,” even rejecting photocopies of Aadhaar or other forms of valid photo ID.

In further ID-related confusion, the UIDAI has also had to issue many warnings, including one just a few days ago, against “smart” Aadhaar cards, which unscrupulous merchants are telling people that they need to buy. These plastic Aadhaar cards are often unusable.

This April, the UIDAI released an updated format for the QR codes issued on Aadhaar documents and e-documents. The new format contains the UIDAI’s digital signature as well as some of the holder’s demographic details, thereby verifying that an Aadhaar is genuine.

But the updated QR code only made its debut well after the vast majority of people in the country had already enrolled in the scheme—over 99% of the population aged above 18 had Aadhaar by January 2017. Anyone wishing to forge an Aadhaar can circumvent the system’s new rigour by using the old QR code format and claiming the document is from before this April.

It’s not clear whether the supreme court will weigh in on whether Aadhaar can be used as a photo ID. “The Aadhaar Act does not define the Aadhaar card, it defines the Aadhaar number, and the Aadhaar number doesn’t make sense without authentication. So at least my personal view is that Aadhaar as an ID has no value without authentication,” Bhatia said. “But that’s open to debate.”