On Nov. 16, 1860, a ship carrying 342 indentured Indians arrived in South Africa, marking the beginning of a long and painful period in the history of the Indian diaspora in the region.

Today, South Africa is home to the largest population of people of Indian descent (1.3 million as of 2015) on the continent. But for long, being a descendant of indentured labourers was a source of shame, according to Zainab Priya Dala, a writer and fourth-generation South African Indian. It’s only recently that the Indian-origin community has gradually begun to embrace its history, commemorating events like the anniversary of the arrival of the first ship, she says.

“Now people have access to records and can trace where their families came from. So, a lot of people are looking and saying, I want to know what my heritage is,” Dala, 43, told Quartz.

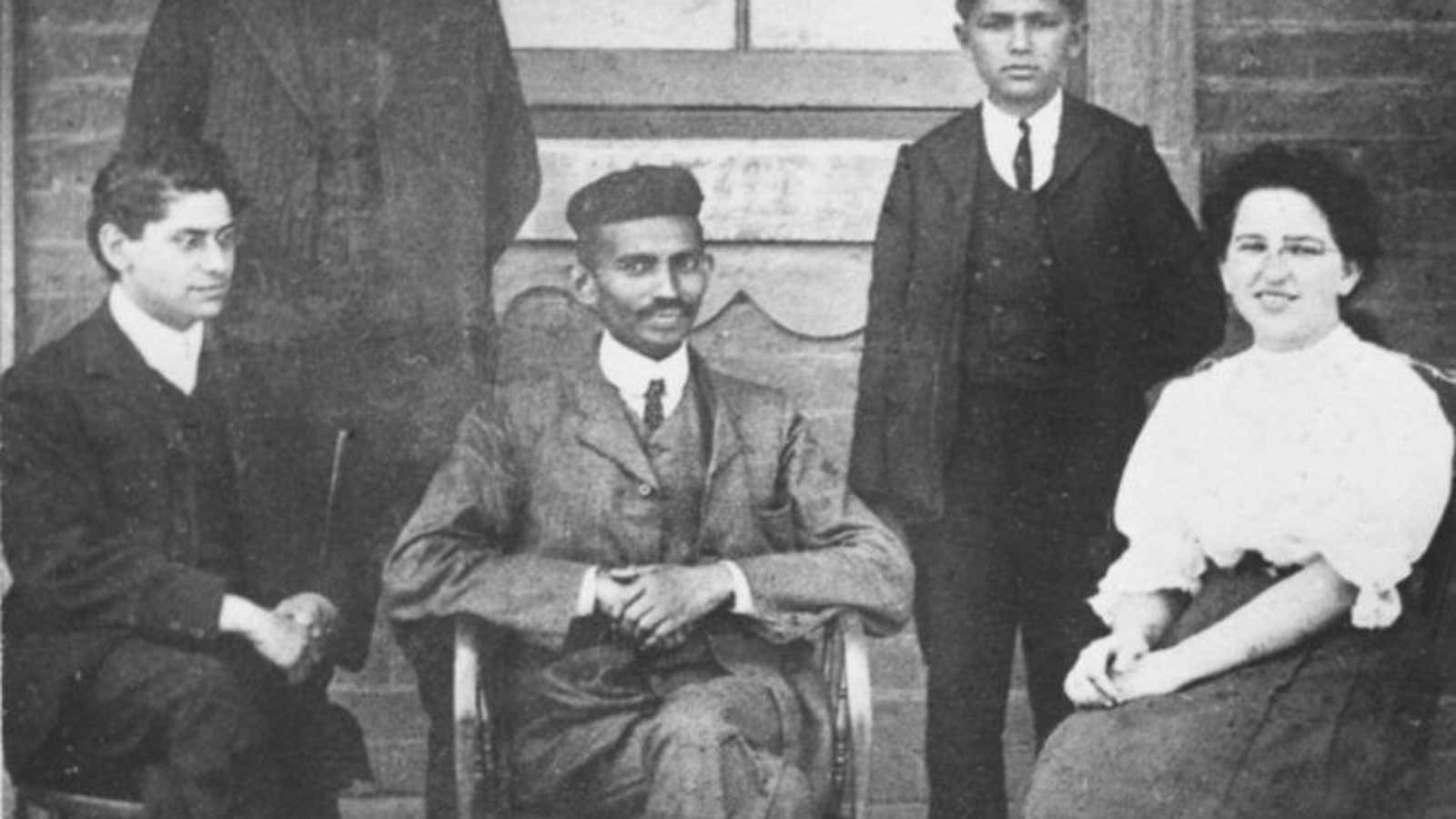

Around the world, the South African Indian community is associated with Mahatma Gandhi, whose 21 years in the country were formative in his mission to lead India’s freedom struggle. But Dala’s new book, What Gandhi Didn’t See, published by Speaking Tree, is an attempt to expand that narrative with essays about what it’s really like to be of Indian origin in South Africa.

Dala’s great-grandfather arrived in Port Natal at the age of 19 from a village in Uttar Pradesh. Like thousands of others, he was put to work under punishing conditions in the sugarcane plantations. He eventually managed to buy himself out of indenture, but died before getting a chance to return to India. His descendants, including Dala’s father, made South Africa their home, and Dala grew up and still lives in a sugarcane farming village near Durban.

Her book is a personal account that captures the South African Indian community’s history of erasure, life under apartheid, and its modern-day mixed identity that embraces Bollywood and Indian traditions, besides South African culture.

Edited excerpts from Dala’s conversation with Quartz:

How has the position of the Indian diaspora in South Africa changed over time?

The South African Indian diaspora has changed with history. The majority of us came as indentured labourers. Colonialism was the first thing we grew as part of. When indenture was abolished, there was apartheid. So we grew with apartheid. We lived under the apartheid regime, not as a white population; we were seen as part of the black population. A lot of us still remember the time when there was no equality.

It’s only after Nelson Mandela was elected as president (in 1994) that South African Indians saw themselves as a diaspora that is not part of some horrible subjugation in history. We’re still very young.

In your book, you mention that “caste has become obsolete” in the Indian community in South Africa, but there are new divisions. Can you tell us more about the differences within the community?

Everybody that came on the ships from India was called jahaji bhais because they came together on a ship (jahaj) and caste was thrown away if you crossed the ocean. So when the Indians came here, they formed a new identity that was without caste.

But class became the dividing line. There was the indentured labourer class and there were “passenger Indians,” who came as businessmen. That’s the dividing line. Although it’s not obvious, it’s still there as part of people’s history. The indentured labourers had to start from scratch when it came to economics, and a lot of them are still living in conditions that are far from ideal.

Another big dividing line which I’ve noticed is colour. For some horrible reason, people with fairer skin are treated better. It’s got to do with movies and Bollywood. Bollywood is huge in South Africa.

Why did you decide to write this book now?

It was a deeply personal decision. One of the reasons is having my own children who are old enough to ask me questions and who are learning about history in school. When my daughter came home and started asking me about Gandhi, I realised I didn’t know that much. And I was embarrassed. It made me realise that even though as South African Indians we are identified with Gandhi, most of us don’t really know much about him. This book is almost a conversation with my children about their mother.

And I’ve also been thinking about deletion. We spend so many years deleting our history and wanting to be white because we thought being white was the best thing on Earth. But it’s only now that we feel like we have permission to embrace who we really are and where we came from. Twenty years ago, I would never have spoken about this.

Can you tell us more about the relationship the Indian-origin community in South Africa has with Gandhi?

We didn’t know much about Gandhi because we weren’t taught. In schools, during apartheid, we were not allowed to learn about anybody who was not white. So, Gandhi never really came into our conversation.

I speak to a lot of people in the streets; when you talk about Gandhi, they always say, I didn’t really know much about him. I sometimes feel that although Gandhi was doing large things at a macro level—he was responsible for eradicating indenture—people in the farms, where most of the indentured labourers still live, I don’t think he connected with that. These small things would have made a huge difference…the indentured labour community would have felt like they were being seen by someone.

There is so much more to us that is not part of Gandhi’s narrative.

What do you want South African Indian readers and Indian readers to take away from your book?

With the South African Indian people, and the South African people at large, I want them to feel a sense of pride in themselves, in their community and their strong lineage. I’d like the younger generation, like my children’s, to begin to be proud and not ashamed of their heritage. I see a lot of shame when it comes to being descended from indentured labour; I hope that me speaking out, will make people proud of where they came from and they will start looking for their families and villages in India.

With Indian readers, I hope they see that there is a group of Indians living in South Africa with very similar lives to them.