Outside a mud house in an urban slum near Patna, a city in eastern India, an older woman is perched atop a wooden cart, waiting for her daughter-in-law, with whom she has a bone to pick. When a local nonprofit named the Centre for Environment and Energy Development (CEED) distributed new wood-burning cookstoves in this slum, each family received only one. It went to the woman’s daughter-in-law.

I ask if I can see her daughter-in-law’s new cookstove. She waves me into a tiny, one-room mud home, where an old, traditional cookstove, or chulha, sits in the windowless, soot-painted kitchen. In the entryway, given pride of place, is a different, second stove—one powered by liquified petroleum gas (LPG). The woman’s grandson points at a high shelf in the living area, where the wood-burning cookstove from CEED is perched, inside its original cardboard box, unused.

This is not an unusual fate for advanced biomass cookstoves. (“Biomass” refers to non-fossil fuels, including wood, animal dung, and agricultural byproducts.) Studies have shown that these cookstoves have not caught on in low-income parts of the world, despite the decades of effort and hundreds of millions of dollars that the nonprofit sector has spent trying to convince people—almost always women—to use them.

The advanced cookstoves are meant to cut down on the toxic gases that come from burning biomass on traditional stoves or open fires. Globally, more than three billion people use either coal, kerosene, or biomass for cooking, and the fumes from these indoor fires constitute the second leading environmental cause of death in the world, after outdoor air pollution. Some 3.8 million people die prematurely each year from diseases related to indoor air pollution, such as pneumonia, stroke, heart and respiratory diseases, and cancer.

It has long been assumed that giving people around the world better cookstoves is an easy and effective way to save lives. So why aren’t those who really need the stoves using them?

In 2010, the UN Foundation and Hillary Clinton, the US secretary of state at the time, launched the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves. At the heart of their plan were “clean” cookstoves that would burn biomass more efficiently and cleanly than existing stoves. They would reduce the amount of wood needed for cooking, which would, in turn, cut down on deforestation and help tackle climate change.

The appliances cost between $25 and $40 (Rs1,790-3,500), which is expensive in many countries, so subsidies poured in from development organisations. But soon afterward came health studies indicating that the stoves, once in the field, didn’t actually improve the health of the women and children who were disproportionately exposed to indoor fumes.

“I’m a health scientist, so basically my criterion is, what would I be happy with my pregnant daughter using?” says Kirk Smith, a public health scientist at the University of California, Berkeley. “There isn’t even one biomass stove in the world that meets that criterion.”

The community of clean cookstove proponents and developers, known as “stovers,” came out of the appropriate technology movement of the 1970s, in which (mostly Western) experts argued that poorer people are stuck in poverty because of simple, inefficient technologies that could, and should, be easily improved. One of these unsatisfactory technologies is the humble cookstove, which continues to kill millions of people with fine particulate matter, carbon monoxide, and other fumes at levels well above safe limits. That level of exposure is particularly toxic to children under the age of five; almost half the global deaths from pneumonia among this age group can be traced to indoor air pollution from cookstoves.

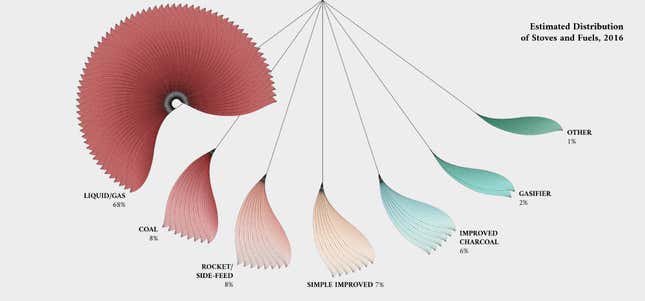

In the years since the clean cookstove movement began, stovers have engineered a variety of improved cookstoves, including the chimney, rocket, and charcoal stoves. The cleanest of them all are gasifier stoves, which contain a fan. A class apart are stoves that burn LPG, which is made from the propane or butane left as a byproduct of fossil fuel extraction. Finally, there are biogas, alcohol, and solar stoves—but these are rare and expensive.

In 2002, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) formed the Partnership for Clean Indoor Air, a group made up of nonprofits, manufacturers, and other stakeholders who supported initiatives to improve cookstoves in lower-income countries. The agency championed the kinds of advanced biomass stoves that use local, renewable woody resources, rather than stoves that use climate-changing fossil fuels like LPG. The EPA believed that better biomass stoves could halve exposure to toxic fumes, thus improving women’s health and reducing rates of severe pneumonia in kids.

The partnership was a precursor to Clinton’s 2010 Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves, which set a new, ambitious target of converting 100 million households to clean stoves by 2020. But Alliance members decided that they wouldn’t just give the stoves away; rather, they would create a global market for clean cooking solutions. Small businesses would sell at village shops at a profit, solving the air pollution problem and boosting the economies of low-income communities at the same time.

But the Alliance never defined what a “clean cookstove” is. No one had yet calculated a “safe” level of cookstove emissions. It wasn’t until November 2014 that the World Health Organization (WHO) released its first indoor air pollution standards, setting acceptable levels of exposure to fine particles and carbon monoxide from stoves—and most of the “advanced” cookstoves promoted by the alliance didn’t meet the new criteria. “So, suddenly, the alliance was in a situation of promoting so-called clean stoves that weren’t clean by WHO standards,” Smith says.

Not only that, but these cookstoves performed even worse in the field than the alliance had expected, having little to no effect on quality of life. In 2012, scientists from Harvard published the result of tracking a project to hand out chimney cookstoves—as in, stoves with chimneys that direct fumes out of homes—in Odisha, India, over four years. They found that, even though there was an improvement in the first year of the programme, over time women stopped using the new stoves, and most households still ended up with the same hazardous air as they’d had with the traditional chulhas. The key realisation was that people simply didn’t value the stoves enough to maintain and continue using them. It’s a pattern that has been repeated across the world.

Further indoor air pollution studies have found even more problems with stovers’ assumptions and plans. The biggest example is a 2017 study in rural Malawi in which scientists compared 10,750 children from households that used either a traditional cookstove or a fan-driven gasifier stove, which is the cleanest improved biomass cookstove available on the market today. The researchers were surprised at how frequently the advanced stoves broke down, given that “these products had been specifically designed and developed for the indications, end users, and environments in which [researchers] assessed them.” They found themselves acting as a repair service, so that the families they were tracking would continue to use the new stoves. Still, by the second year, usage fell to 50%.

Even worse, the scientists found that the new cookstoves hadn’t reduced rates of pneumonia in children under five. Either the cookstoves were not actually cutting indoor air pollution or the Malawian kids in the study were being exposed to so many other air pollution sources—burning garbage, for example, or tobacco smoke—that addressing cookstove smoke on its own wasn’t enough to protect against pneumonia. Both conclusions undermine the alliance’s raison d’être.

With the writing on the wall, the cookstove sector is now changing direction. Last month, the Global Alliance changed its name to the Clean Cooking Alliance, and the organisation is now promoting the act of clean “cooking” rather than cookstoves specifically. The focus is no longer primarily on the kind of fuel being burned.

Biomass cookstove makers are now fighting a rearguard action against these criticisms. Browsing the Clean Cooking Catalog, you can find new kinds of biomass stoves, like the compact Mimi Moto gasifier, which, the organisation claims, is extremely clean—and ideal for households that cannot afford LPG. And there are scattered examples of local-level cookstove companies, like Inyenyeri in Rwanda, that seem to be having success in getting people to fully convert to biomass.

There’s one final argument that’s still used to advocate for advanced biomass cookstoves: they’re undeniably better for the climate than LPG is, because fuels like wood are renewable. While true, this is an argument with fewer takers. “No matter what the poor are using to cook, it’s not going to affect climate change,” argues Smith. “It’s the rich of the world that are causing climate change.”

If not biomass, then what? LPG stoves are the only other such appliances that meet WHO pollution standards. Some nations, like India, are rapidly expanding access to LPG through subsidies and social welfare programmes. But other nations are not as lucky or rich, says Tom Price, the director of strategic initiatives at Inyenyeri. In Rwanda, increasing the number of people using LPG from 1% to 10% would create a deficit of $100 million, he says.

“Obviously, an LPG stove is very clean, but if someone cannot afford it, who cares?” he says. “We’re solving the problem for the rich, but not solving the problem for the base of the pyramid.” For those people, biomass stoves remain the solution, Price claims. But he admits that, out of the roughly 2,000 stove companies worldwide, not a single one has succeeded in building a stove that’s simultaneously clean, accessible, and profitable to sell at scale.

Price believes that his company will be the first. Inyenyeri distributes the Dutch-made Mimi Moto, which has been certified by Colorado State University as the best biomass cookstove available today. (However, it has thus far only undergone testing in the lab, not in the field.) It costs $75, so the company gives the stove out for free and then charges for the fuel—pellets made from eucalyptus. Price claims that the average Rwandan family spends $23 a month on charcoal, while Inyenyeri supplies a month’s worth of pellets for $16, therefore saving users money. And for those who prefer to collect free wood, Inyenyeri allows wood to be exchanged for pellets. In order to break even, though, the company need to hit 75,000 customers. Right now, they have 4,000.

Similar gasifier stoves are being put through trials by the World Bank in Laos and other countries. However, Fiona Lambe, a research fellow at the Stockholm Environment Institute, urges caution. The 2017 Malawi study that found gasifier stoves didn’t work in the field as well as in the lab was focused specifically on a model of stove designed and manufactured by Philips in the Netherlands. It’s yet to be seen if the Mimi Moto will fare any better in the real world.

One answer to the cookstove conundrum might be to promote and perfect a variety of stove types. Just as people in higher-income countries, like the US, use various devices to cook—gas burners, microwaves, tea kettles—most poor women, when given a choice, also like to use a variety of methods and fuels, from traditional stoves to LPG to biomass. (This is called “fuel stacking” in the world of non-governmental organisations.)

If people have money, they’ll prefer LPG for its convenience. It’s an aspirational product, just like a flat-screen TV. If they don’t have money, they’ll prefer traditional cookstoves, like the Indian chulhas, which have the bonus of making better-tasting food than the average biomass stove can. Biomass stoves tends to only be preferred in select situations, such as cooking outdoors, because they’re often portable. But studies suggest that there is virtually no advanced biomass cookstove on the market today that is as clean, in terms of air pollution, as an LPG stove is.

As such, it’s better to view the clean cookstoves problem as part of a cooking system, where different people bring different needs into play, depending on their specific situation, their income, and their family size. A biomass stove can still be useful in certain situations. It’s just not useful in every situation.

“No one is using any one stove,” says Lambe. “I’ve never come across a household that will use just a three-stone fire. They’ll have something for emergencies—a kerosene burner, a charcoal stove, something.” Trying to replace all these diverse cooking needs with a single true stove is unrealistic, she argues. “As soon as [the cookstove] gets into the household, there’s so many things that can happen. There’s a huge difference in terms of what happens in real-life situations and the lab.”

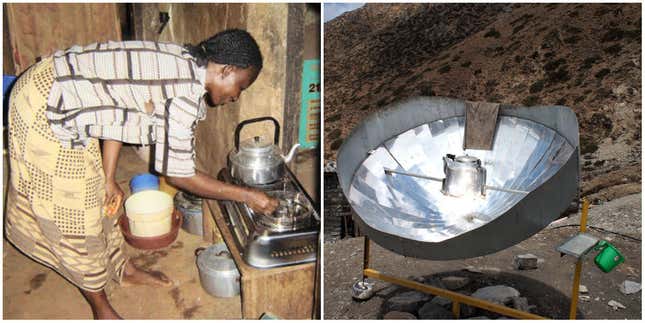

In Patna, the mother-in-law’s neighbor, Devi, also has an advanced biomass cookstove—she uses it to cook outside. She has an LPG stove as well, on which she whips up a quick tea and breakfast each morning, but she can only use it sparingly; a refill costs Rs700 ($9.50). She prepares lunch on her traditional stove.

Devi demonstrates how she lights the biomass cookstove. She fills the chamber with wood, picks up an empty plastic detergent packet, sets it on fire, and drops it into the stove to give the firewood a kickstart.

Noxious fumes fill her courtyard, blowing into the faces of her three boys.

This article was originally published on How We Get To Next, under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence. Read more about republishing How We Get To Next articles. Sign up to the How We Get To Next newsletter here. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.