Wayanad, a rural district in the southern Indian state of Kerala, is the kind of place that could have inspired the descriptions of the Garden of Eden.

It is a land of lush hills, covered in foliage of every shade of green. Mangoes and bananas big and small—green, yellow, and red—ripen in the sun, while gigantic jackfruits hang precariously from thin-trunk trees. Flowers of the most intricate shapes dot the sides of the streets, and the occasional kingfisher flies from one tree to another, with its impossibly blue feathers. On inner roads, signs warn of elephant crossings, while birds whistle their enchanting calls. There might even be tigers hiding in the jungle.

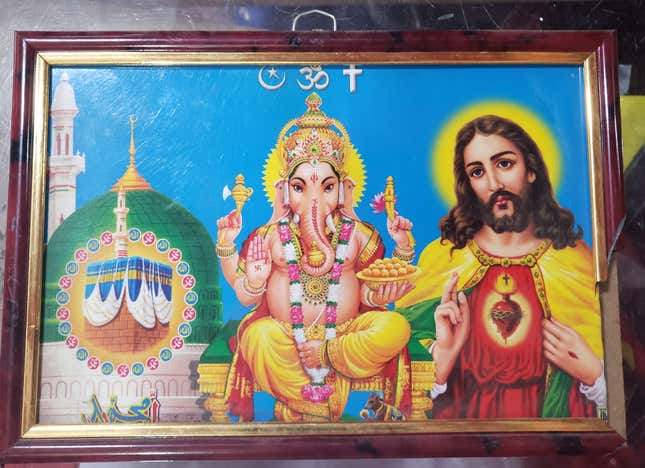

It makes sense that this part of India—where Hindus, Christians, Muslim and all others live together with ease—would be known, like the rest of Kerala, as “God’s own country”—a tagline that stuck from an especially successful advertisement campaign for the state in the 1980s. And God’s own country—or a significant part of it—is Communist.

The Comunist Party of India (CPI), was voted into power in Kerala in 1957, as one of the world’s first democratically elected Communist governments. The state has held onto a strong leftist identity, electing a number of Communist chief ministers since, swinging between the Indian National Congress and the Communist-led coalition. While members of the coalition often win seats in the state assembly, Congress party candidates have traditionally had an easier way in national Lok Sabha elections, with voters drawn toward a party with a better chance of leading the nation.

But the margins are typically narrow: In 2014, the Wayanad seat was won by the Congress-led coalition with a margin below 2%, or just 20,000 votes. And this time around, the game is a little different. The Congress candidate is Rahul Gandhi, the party’s leader, whose father Rajiv Gandhi, grandmother Indira Gandhi (both assassinated, the latter while serving), and great-grandfather Jawaharlal Nehru were prime ministers of India.

As is traditional for his family, and himself, Gandhi is running for a seat in Amethi, in Uttar Pradesh. But he is on the ballot in Wayanad, too: In accordance with the Representation of People Act of 1951, candidates can run in up to two constituencies. Should they be elected in both, they have 10 days to recuse themselves from one of the seats, which is then up for grabs through by-elections.

In a tough election, one can see why Gandhi chose Wayanad—its large Muslim and Christian communities are deeply loyal to the Congress, while the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and prime minister Narendra Modi are widely disliked. It gives him a safe way to make it to parliament.

But for the members of the Left Democratic Front (LDF), Kerala’s left-wing coalition of the two main Communist parties and other smaller parties, Gandhi isn’t in Wayanad as part of his battle against the right: It is the left he is taking on.

“Two sides of a coin”

“Why did he select here? It is a clear signal to corporations,” says AR Sindhu, the all-India secretary of the trade union organization CITU, who is campaigning for the LDF in Sultan Bathery, Wayanad. The cialition’s candidate, PP Suneer, is a 51-year-old politician and the head of the CPI. He hails from the Malappuram district, but as the party leader for Kerala he has spent time campaign in Wayanad, and is well known in the area.

The leftist coalition in Wayanad opposes many of Congress’s economic policies, and the party leader taking on the LDF here signals that the demands of workers will not come before the interests of big money. The Congress party platform, Sindhu says, “has nothing about taxing the corporate, nothing on minimum wage.”

Krishna Prasad, a former member of the Kerala assembly representing the CPI and the treasurer of the Communist peasant organization, All India Kisa Sabha, notes that the LDF had made it abundantly clear that its candidates, if elected, would support a Congress-led government in the Lok Sabha, as “the foremost priority is to defeat the communal BJP.” But, Prasad says, the LDF would bring a further-left contingent into the coalition. That’s precisely, Sindhu and Prasad argue, what Gandhi is in Wayanad to prevent.

“The BJP is communal, authoritarian,” says Sindhu. Yet in terms of economic policies, the Congress isn’t very different from the BJP, in the eyes of the LDF. The BJP, say Sindhu and Prasad, has essentially moved forward neoliberal policies initiated by Congress. While they acknowledge an important difference between the parties when it comes to the political ideology, they consider them the same economically.

“Both are the same, two sides of a coin,” says Sachi, an LDF veteran who has been campaigning for the party for 40 years. Sachi mentions the role of the Congress in introducing the economic liberalization policies then pushed forward by the BJP which, he says, have caused tremendous damage in Wayanad. He blames especially the Association of South East Asian Nations Free Trade Area agreement for dramatic drops in the prices of coffee, pepper, and other cash crops, the primary source of income in Wayanad.

Unlike Gandhi, who has barely ever set foot in the constituency, Sachi highlights the fact that Suneer knows the area’s issues well, and the team working with him has served Wayanad for decades. “We have a separate manifesto for Wayanad,” Sachi says. “That is our value addition.” The LDF also has the support of tribal groups, which make up a large portion of the Wayanad population.

And as star Congress campaigners, including Rahul Gandhi’s charismatic sister Priyanka, have taken Wayanad by storm, landing by helicopter and delivering speeches at huge rallies, the LDF has opted for the opposite approach—a door-to-door, grassroots campaign. “This time, we are prepared to fight,” Sachi says.

Shaping the battle with Gandhi

The LDF is not going down without a fight. Once Gandhi announced his surprise candidacy from Wayanad, the LDF took him on directly, printing a pamphlet with 10 constituency-specific questions, asking whether he is willing to withdraw from the ASEAN agreement; support blocking the import of coffee and pepper; regulate dairy imports; and back new pro-labour regulations. “We say: Rahul Ji, how do you address these problems? You came to attack the Communist party but your best choice is to attack the BJP.”

To take on the high-profile outsider, the Communist party coalition—the only group, its campaigners hold as a badge of pride, that does not pay its volunteers and instead lives off its members’ donations—has mounted a far-reaching campaign. As of April 20, a team of 10,000 people had distributed 100,000 pamphlets and manifestos, visiting each home in the district four times.

The party is confident that one-to-one engagement will be effective to counter Gandhi’s star power, as people are reminded that the Communist party was able to pass debt-relief measures for farmers in Wayanad in 2007, when it had the highest per-capita rate of farmer suicide in the nation, and introduce cooperative projects that ensured a better livelihood. The LDF also takes credit for the impressive development standards of Kerala, which has the highest literacy rate and life expectancy in the country. “People know,” Sachi said.

On the street in Wayanad, however, it is hard to find people who think Suneer has much of a chance. “He is a good man and everyone knows him,” says Yashwin Adakkal, a student from Kalpetta. “But people will go for Rahul Gandhi, because in people’s eyes he is a big candidate.” Indeed, most of the people Quartz spoke to indicated without hesitation their intention to vote for “Rahul ji.” “He is honest I think,” says Shiva, who owns a shop selling religious paraphernalia. “He will lead our country.” There is, of course, a chance Gandhi may recuse himself from the seat should he win Amethi, too. People here don’t seem too concerned about that.

On the last weekend of campaigning, the Congress party sent Priyanka Gandhi to support her brother on the campaign trail, and thousands of people—evenly split between women and men—waited for her for hours in the Seetha temple ground of Pulpally. They shielded themselves from the sun as best as they could—using folded banana leaves for hats and lifting plastic chairs to block the rays.

As her helicopter landed, the crowd was frenzied. When she arrived on the stage, amid cries of “Priyanka ji zindabad” (“Long live Priyanka”), people seemed spellbound. She spoke in English to a crowd that mostly doesn’t understand it, as a translator interpreted. Occasionally, the crowd erupted into cries of support when they heard words they understood: “sisters,” “love,” “respect.”

Many left before the speech, to avoid the inevitable congestion at the end. Street vendors sold Congress souvenirs. One showed portraits of all the Gandhi family: Indira, Rajiv, Priyanka. The stall also had a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi (who is no relation to the political dynasty).

Customers gathered around pointed to the image of the family’s latest candidate to lead the country: “Rahul Gandhi,” they said. “Prime minister!”

Read Quartz’s coverage of the 2019 Indian general election here.