Fishing isn’t bad business in Porbandar, along the coast of Gujarat, India’s westernmost state. It provides employment for half a million fishermen, who manage to earn up to Rs20,000 a month (about $290), or twice the country’s average per capita income. Boat captains can make around Rs30,000.

India’s industrialization and liberalization have not challenged the livelihoods of Porbandar’s fishermen. In other parts of the country, local fishermen have all but been put out of business by larger organizations. But every year, an estimated 200 Porbandar fishermen end up in Pakistani jails, charged by the Pakistan Maritime Security Agency (PMSA) with having crossed into Pakistan’s waters. The fishermen maintain most of arrests occur in international waters, or in the so-called No Fishing Zone. As of Apr, 25, 111 fishermen remain in Pakistani jails.

Porbandar’s fishermen are looking for Narendra Modi’s government—which they believe will come back for a second turn—for help.

Not Pakistan’s problem

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Modi’s escalating anti-Pakistan rhetoric doesn’t necessarily find a welcoming audience among the fishermen. For them, the main culprit of their predicament isn’t Pakistan—it’s pollution. A lack of enforcement of existing laws on dumping pollutants into the sea have pushed them farther out into international waters to begin with. This is a problem that is for the government of India, not Pakistan, to fix.

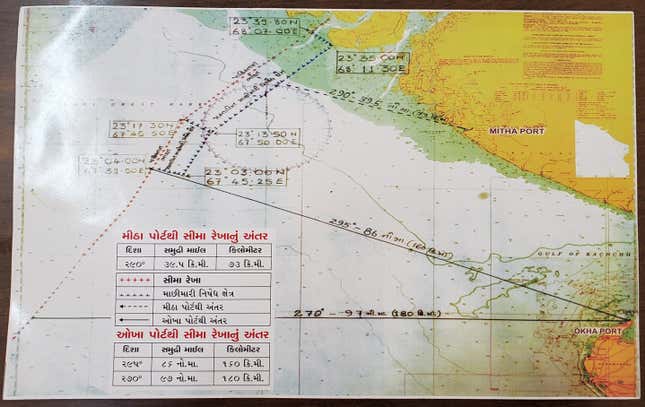

Fifteen to 20 years ago, fishermen would get a good catch within 20 to 50 km of Porbandar, explains Jadavbhai K. Postariya, president of the Shree Porbandar Machhimar Boat Association (SPMBA) of Porbandar. A five-day trip was enough to come home with a full load, about eight to 10 tonnes of fish. Now fishermen need to be out in the water for close to a month, and go as far as 250 km from Porbandar. Pollution that has expanded with industrialization, and fish simply no longer gets close to the coast, he says.

Industries coming up on the coast of Gujarat—from Surat to Ankeshwar, from Kodinar to Porbandar—have been ignoring waste-disposal regulations, releasing untreated water into the sea. “Marine vegetation has been destroyed,” says Postariya, “so fish doesn’t come near the coast to breathe.” This forces the fishermen to go further up along the Kutch coast, into international waters, where they are an easy target for Pakistani authorities.

What India’s government can do

It is not always easy for fishing boats to have a precise understanding of where they are on the map, despite GPS systems. The Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) is working a pilot phase of a two-way communications system, called NavIC, which would help fishermen check their position with the coastal guard’s support.

Occasionally, fishermen from Pakistan are arrested and held in India. However, Pakistani fishermen don’t need to move that far away from their coasts to be able to catch fish, because their waters are far less polluted.

According to international maritime law, fishermen arrested for crossing into foreign waters are to be released within 90 days. Delays are routine, however, and strained relations between India and Pakistan don’t help. Crews—typically seven or eight fishermen, plus the captain—often end up spending about a year in Pakistani jails.

While they are held, the government of Gujarat pays fishemen’s families 300 rupees per day—though it is not enough to make up for the lost income. On top of it, the boats are lost: Until 2003, says Postariya, the PMSA used to return the boats once it released the crews, but now holds onto them, selling them at local auctions. For the owners (typically, not part of the crew), it can amount to a loss of about 50 lakh rupees (about $72,000) per boat, for which they get no compensation.

It is Postariya’s hope that Modi’s next government will take care of this issue, as it had promised in the past. In 2014, Modi was involved in negotiations to get back some of the 1,000 boats held by Pakistan, of which 57 were returned to India.

“The present government is sympathetic to solving the problem,” says Postariya. “Since 1988, we had been asking for an independent fisheries ministry and it has now been announced.”

The hope is that the government will also address the root cause of the problem by imposing anti-pollution action. “Effluent treatment plants should be made mandatory,” he says, “and there should be strict implementation of pollution laws.”

What will not help is the escalating anti-Pakistan rhetoric promoted by the ruling party and the government.

“Better relations with Pakistan will help the fishermen,” Postariya says.

Stavan Desai contributed reporting for this article.

Read Quartz’s coverage of the 2019 Indian general election here.