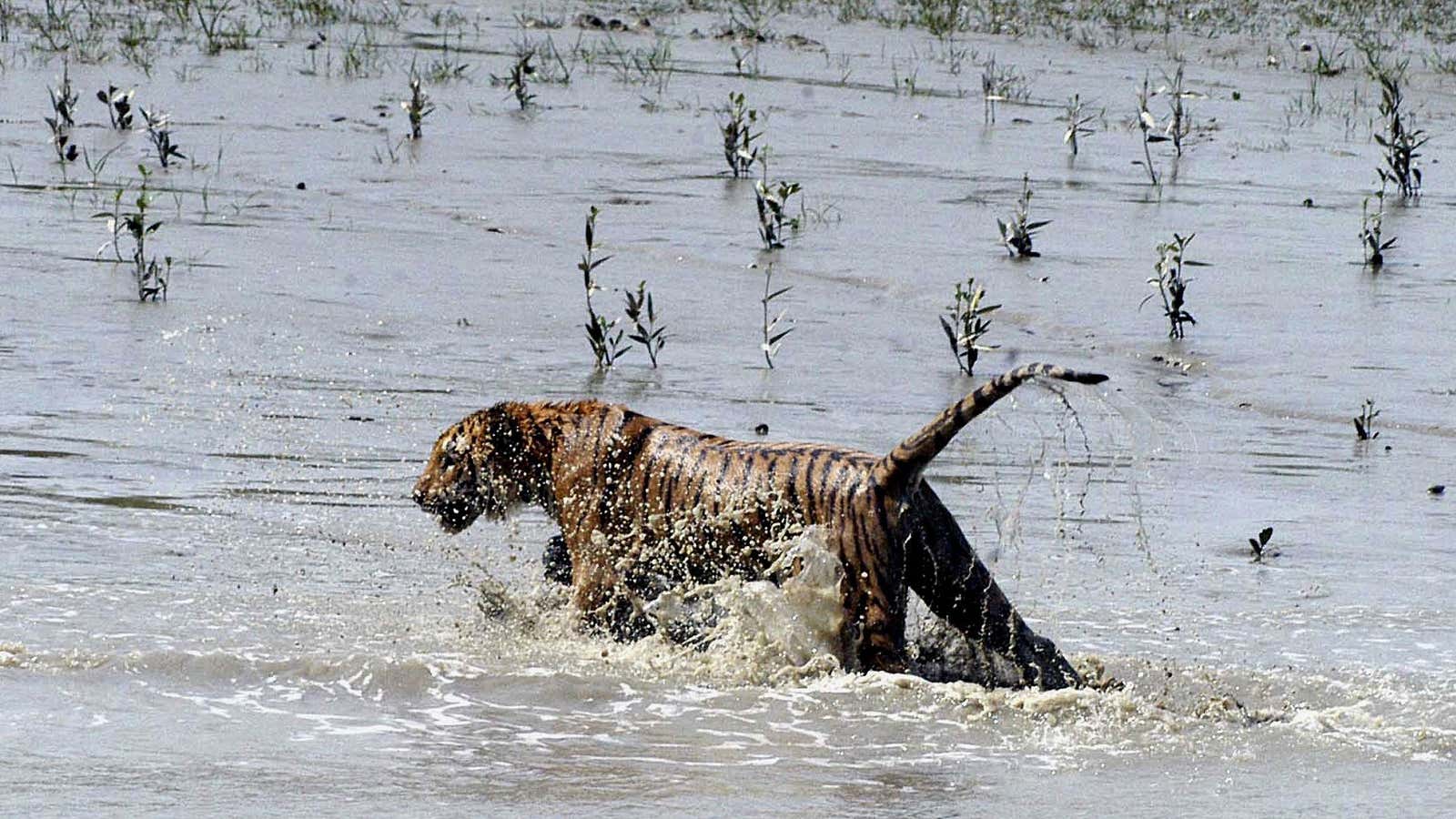

The Sundarbans—a vast swath of mangrove where the Ganges river meets the Bay of Bengal—is a wild place to live. Those brave enough to work here, many of them extracting a honey so delicious it’s been dubbed “liquid gold,” others fishing the region’s rich waterways, face near constant threat from the coastal forest’s preeminent inhabitant: the Bengal Tiger.

Rising sea levels and shrinking habitats, the dual menace of climate change, is making things worse—driving tigers and humans ever closer to each other. Increasingly, both must fight for their lives. Yet despite all these natural threats, the people living in this region fear even more something else entirely: politics.

India today will release the results of the country’s Lok Sabha, a month-long process to elect India’s House of Representatives. The country’s national Election Commission often holds up the Sundarbans as an example of the extent to which the central government will go to make sure everyone in India—the second most populous country in the world—gets to vote. Photos of election workers precariously carrying electronic voting machines on boats that connect the various regions of the Sundarbans is so familiar its a near cliche.

But for the actual voters of this region, election time is not charming. This is a land where people are forced to choose between poverty and work that can be lethal. Yet equally lethal can be the political fights, which in these areas of West Bengal are the most violent of the country. Party members in the area are used to ruthless, at times deadly, fighting with the goal of intimidating their adversaries, as well as the voters who support them. As is so often the case in politics, the end game isn’t so much to help this troubled land, but to retain—or gain—power.

As a result, election time can be more dangerous than the Bengal Tiger.

Of tigers and men

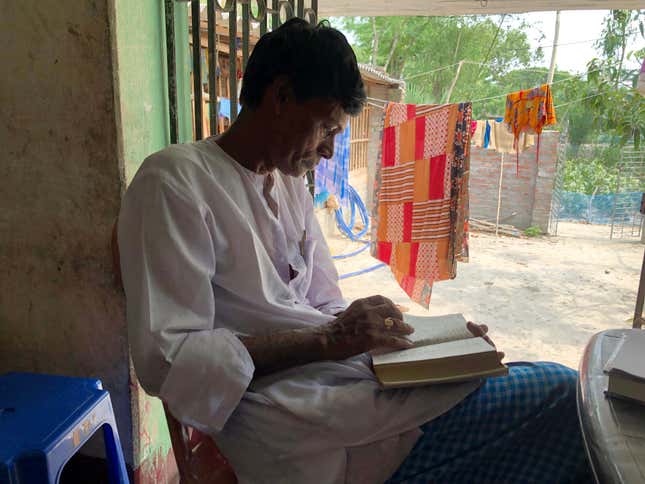

Bongeshar Mandal, 51, lives and works in the Sundarbans. For 22 years, Mandal has taken annual trips into the jungle to collect mangrove honey, a delicacy. In all that time he’s been lucky. He never stood face-to-face with a tiger, the profession’s biggest risk. Recently, his luck changed.

As per custom, he had ventured into the jungle with a group of about a dozen men. Left alone for a rare moment to guard the team’s boat, a tiger seized its opportunity. Tigers, the local people say, are so determined that if they see prey in the distance they will track it down, even if there is an easier, more appetizing prey somewhere closer. So Mandal knew his life was on the line. He carefully moved to grab some firecrackers they kept on the boat. He lit them off, scaring the predator just long enough for the larger group to re-join Mandal. Deterred by the large numbers of people, the tiger turned away.

People here often manage to scare tigers away with fire or even long sticks. But it’s not a fail-safe way to survive. Many are attacked and mauled, sometimes losing limbs. Dozens of times every year, it is their life they lose. Tigers kill more people here than anywhere else in the world. And it’s the only place in the world where tigers routinely attack people.

Most of the tigers of the Indian Sundarbans—74, according to the 2014 tiger census—live in the natural reserves, protected from the dangers that have caused their near-extinction: habitat loss, hunting, and illegal animal trade. The quintessential embodiment of so-called “charismatic wildlife,” they arguably enjoy more attention and dedicated policy than the people who live near them.

But the various islands in Sundarbans are so close to one another that, when the tide is low, the predators can easily leave the reserve and cross into inhabited islands. The forest authority has installed nylon nets, which provide a psychological barrier to tiger crossings, to protect human settlements. Still, dozens of people a year get attacked, mostly while traveling in the forest, fishing for crabs or collecting honey.

A very long war

The fight between man and tiger is centuries old. Tigers are endangered now, and even the locals understand and support the importance of wildlife conservation. On the other hand, no one is going to fault a resident who kills a tiger in order to protect their cattle, farm animals, or their families. Tigers, it seems safe to assume, would do the same.

If the proximity with tigers weren’t enough, every year between April and May, thousands of men like Mandal venture into the mangrove forest to find local honey. They have been doing so since the 16th Century, says Kanai Sarkar, a writer and historian from the Sundarbans region.

At the time, the honey collectors were from areas that are now on the border with Bangladesh. Authorities gave permission to enter the forest for two weeks to collect the honey. By the 18th Century, people began living on the island. The East India Company encouraged populations from neighboring areas to move to the Sundarbans, giving out 90-year leases for people to deforest and farm in the fertile lands, collecting taxes in exchange.

Eventually, the area grew to be highly populated, and nearly 4.5 million people live here now. It is one of the poorest areas of India, and one that suffers from a range of problems even more threatening than ferocious wildlife.

For one, the islands are essentially melting away. Climate change and rising water levels cause extreme erosion and entire islands have been lost. Scientists project that, at the current pace, by 2030 a dozen islands will disappear entirely, along with the homes of 70,000 people. This doesn’t even account for extreme weather. Cyclone Aila in 2009 destroyed more than 700 kilometers of embankment the islands rely on to keep high tides at bay. So far the government has only repaired about 20% of those embankments, Sarkar said.

Rising sea levels are also reducing the amount of fresh water available in the area, threatening both people and crops.

All of this only makes the tigers more dangerous: Their habitat is shrinking and they, too, are often unable to find freshwater to drink. As a result, the tigers have moved closer to populated areas. Hungry and thirsty, the tigers have become even more aggressive.

People too are forced to venture further into tiger territory. As climate change reduces the amount of sea life in the region, crab hunters and fishermen head further inland to make ends meet. “Whatever we used to get 20 years ago,” says Sitanshu Mondal, a 51-year-old fisherman who has been going out in the delta every day for the past 23 years, “we get less than half.” Sitanshu recently escaped a close encounter with a tiger while he was fishing with his wife during a storm.

According to the official numbers, Sarkar said tigers kill about 100 victims every year. But he says this isn’t but a fraction of the real number of casualties. He likens the ratio of reported deaths to actual deaths to that of reported versus actual rapes. Honey collectors and crab hunters need a government license to venture into the protected area. But many go without one because the processing of permits is often delayed until well after the honey season begins.

If unauthorized collectors get attacked, it just doesn’t get reported. “The [families] don’t tell anyone,” Sarkar said. “And the tears of losing someone stay inside.”

Death by politics

Chandima Sinha, who works for the Nature Environment Wildlife Society, a nongovernmental organization working on habitat preservation, said that the real offense is that the prices set by the government for honey is too low, especially relative to the dangers the work presents. A honey collector usually makes between Rs 5,000 to Rs 6,000 ($70 to $85) in a season.

As a result, honey collectors and crab hunters Quartz spoke with all said they would quit their job in a heartbeat if another form of sustenance was available. Many, for stretches of time, join the ranks of migrant labor heading to other parts of the country.

“I have many sleepless nights when I sit with my heart in my hands,” says Shudha Mandal, whose husband Orun has been going out at night fishing for crabs for 26 years. “Because of the almighty gods,” her husband says, “I have only encountered tigers twice.”

Political candidates should have their choice of issues to address in this region. But many residents here fear making any demands.

Sarkar said that clashes between members of different parties can result in deaths, and deliberate killings of adversaries aren’t unheard of either. People are used to being intimidated out of voting, or threatened if they don’t vote for a specific party. Although central forces have been assigned to guard polling stations to prevent violence, they do not protect threatened residents.

Sarkar said people are terrified of speaking up. He says that even by mentioning what their priorities might be—more jobs or better roads—they fear that those in power may think they are badmouthing their work, or candidates who are focusing on other issues will accuse them of supporting their adversaries. According to accounts locals shared with Quartz, at least two people died in the past few weeks in apparent political killings. As of May 18, the photo of one of the corpses welcomed people getting off the boat in Satjelia, an island in the Sundarbans.

Women are an unusually large, and neglected, part of this constituency. The so-called “tiger widows,” women whose husbands were killed by tigers, make up large parts of entire villages in the area. Impoverished, disenfranchised, and often stigmatized (residents believe that being killed by a tiger is an expression of divine wrath), they are especially reluctant to share their needs. “After the voting, they will speak,” Sarkar said.

“I hope there is no fighting,” says Radha Mondal, who runs a chai shop with her husband and is one of the few women wanting to discuss the election in any way. “[Last election] a lot of people were stopping us from voting; this time it has been fine—but tomorrow we’ll see.”

Sujatro Ghosh contributed reporting to this article.

Read Quartz’s coverage of the 2019 Indian general election here.