Why do companies exist, and why are some large, and others small?

In 1937, a young London School of Economics graduate named Ronald Coase published an academic paper titled “The Nature of the Firm” which questioned why firms exist, when instead they could all be one-person outfits, each contracting with the other.

The reason, Coase said, had to do with transaction costs involved in contracting an economic activity (sales, manufacturing, etc.) outside the firm. When the costs of such contracts were lower within the firm, versus the outside market, the entrepreneur would choose to do it internally.

This insight, which seems obvious now, at the time revolutionised the field of microeconomics. Coase went on to win a Nobel Prize for Economics in 1991 with the Academy citing this paper.

The last 100-odd years of the firm have all largely been in a one-way direction: the average firm has gotten bigger and more vertical as it insourced more and more economic activity.

However, this one-way trend is now ending. Firms are shrinking as much more can be done, much faster, by fewer people.

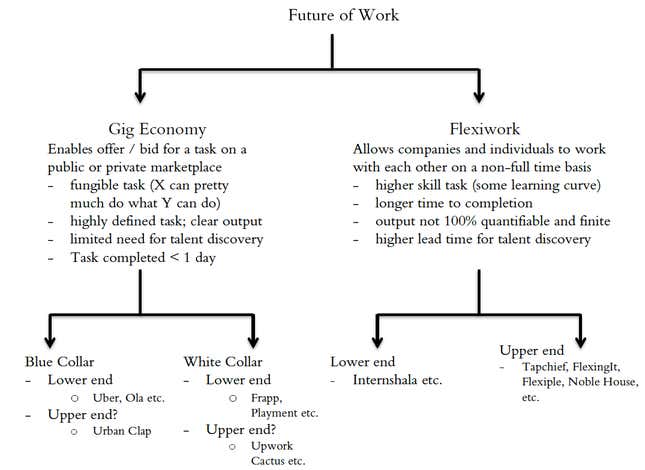

With other related economic trends underway, including the growth of smartphones, cheaper data, and the pressure to save costs, we are seeing two broad trends emerging:

- The rise of the gig economy: While the popular symbol of the gig economy is the Uber driver or the Zomato delivery executive, the gig economy is outgrowing its blue-collar origins fast. There is a strong white-collar element to the gig economy now—from logo designs or content writing at the upper end to labeling pictures for machine learning training data at the lower end.

- The shrinking of full-time roles: Let us call this flexiwork. While primarily led by the need to save costs, this trend is also getting reinforced by the phenomenon that people, especially younger folks, are open to exploring lower intensity engagements, and recognise that part-time jobs can pay sufficiently enough while giving the freedom to have a more easy-paced life.

The Indian gig sector

Historically, in India, we have had an equivalent of the gig model, where workers connect at prominent spots (called labour nakas) in cities and contractors approach to hire them for the day.

With the increasing popularity of cheap handsets and falling internet rates, more and more of these folks will begin to move from just standing around and waiting for work, to taking up jobs on mobile apps.

The Indian gig sector is growing, and creating a new lower middle class. The gig economy is growing in size both at the bottom (lower-paid task end on apps such as Uber, Dunzo, and Zomato), but also at the upper end (think Upwork).

Smartphones, tech literacy, and new business models are transforming attitudes to gig work both among corporates and workers across skill levels in India. We are seeing gig work take off both at the blue-collar end and the white-collar end. Capitalising on these trends are a whole host of startups, aiming to build the Teamlease of the 2020s.

There is little research on the India market numbers. Still, I reckon around 2 million jobs have been created under the digital gig model over the past five or so years, especially at the bottom end. Most of this digital underclass works for the big six gig employers—Uber, Ola, Zomato, Swiggy, UrbanClap, and Dunzo. Some of them may not be new jobs per se, but we now have around 2 million urban lower middle class earning relatively decent wages.

Allied to the emergence of this lower end is also the rise of the upper end of the gig economy, which deals with white collar assignments. There aren’t too many specifically Indian marketplaces such as Upwork or Fiverr yet in India. Instead, there are managed service providers who work with corporates to supply the talent.

Shrinking core and rise of flexiwork

Almost every large company in India today has a cryptically named project under which senior management meets to plan how to reduce employee headcount. And almost every one of us knows at least one middle-aged friend who is now a consultant, having suddenly resigned from what was a well-paying job. Sometimes we are that consultant.

A contracting full-time workforce is a reality today. Besides being driven by the need to reduce payroll costs, the trend is also led by a workforce that is happy to embrace the non-linear rhythms of flexible working.

Unlike the employees who entered corporates in the 1980s, or 1990s, and were happy to embrace a linear career, the millennials and Gen Z employees see their career as a non-linear punctuated progression. They are happy to quit a well-paying job, take a six-month sabbatical and go to Bali (as someone I know has done), and then come back and search for a job.

Where is all this leading to?

I sense a long-term scenario where large companies have much smaller full-time employees, supported by partnerships with more staffing or flexiwork providers.

Accompanying this will be parallel cultural trends such as the end of the stigma attached to short-term or part-time employment, and acceptance of careers that comprise a continuous series of hops across different projects and enterprises.

Perhaps in the future, high-quality talent may prefer to work for multiple employers and could be “represented” by organisations, just like creative artistes are represented by agents.

As part-time or project-based employment becomes more and more common, and as the gig economy booms in parallel, there will be a wave of products that cater to their needs such as insurance for days (and earnings) lost and lending (and savings) products for careers where earnings are lumpy.

At the same time, the government would do well to encourage and facilitate these, by ensuring that they are on par regulatorily with the products catering to what is seen as conventional full-time employment.