Steve Askew, the Australian programming head and (Star TV’s programming chief in India) Sameer Nair’s boss in Hong Kong, came across Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.

“It was very popular (in the UK and Australia) and not at all elitist. It didn’t exclude people. People with average intelligence, like me, or the next viewer could watch and enjoy it equally,” said Askew.

The game show devised by David Briggs puts regular people selected through various rounds on a hot seat, where they answer fifteen questions. It starts with simple questions and a small amount of prize money, which rises dramatically after each round as the questions get tougher. At several points in the game the person on the hot seat can take his or her winnings and leave.

In July 1999 Askew showed a tape of the show to Nair.

[…]

Nair moved fast. He asked Askew to buy the rights for Who Wants to Be A Millionaire from ECM, the firm that had bought the Asian rights from format creator Celador. He then started looking around for someone to make a show like that in India.

He zeroed in on Siddhartha Basu. Siddhartha had worked with Star Plus earlier on A Question of Answers, a current affairs show with journalist Vir Sanghvi, and on Eureka, a science show. A postgraduate in English literature, Siddhartha turned to documentary film-making and then quizzing in the early days of DD (Doordarshan).

By the time Nair began putting together his team for Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, Siddhartha was already a big name on Indian television. He and his wife Anita Kaul-Basu had set up a production firm, Synergy Communications, in 1988. It was producing, among other things, Mastermind India on BBC World.

Just as the new millennium rolled in, Nair called Siddhartha to check whether Synergy could produce a show like Who Wants To Be A Millionaire. “The prospect of getting our teeth into something so large was interesting. We were up for it,” says Siddhartha.

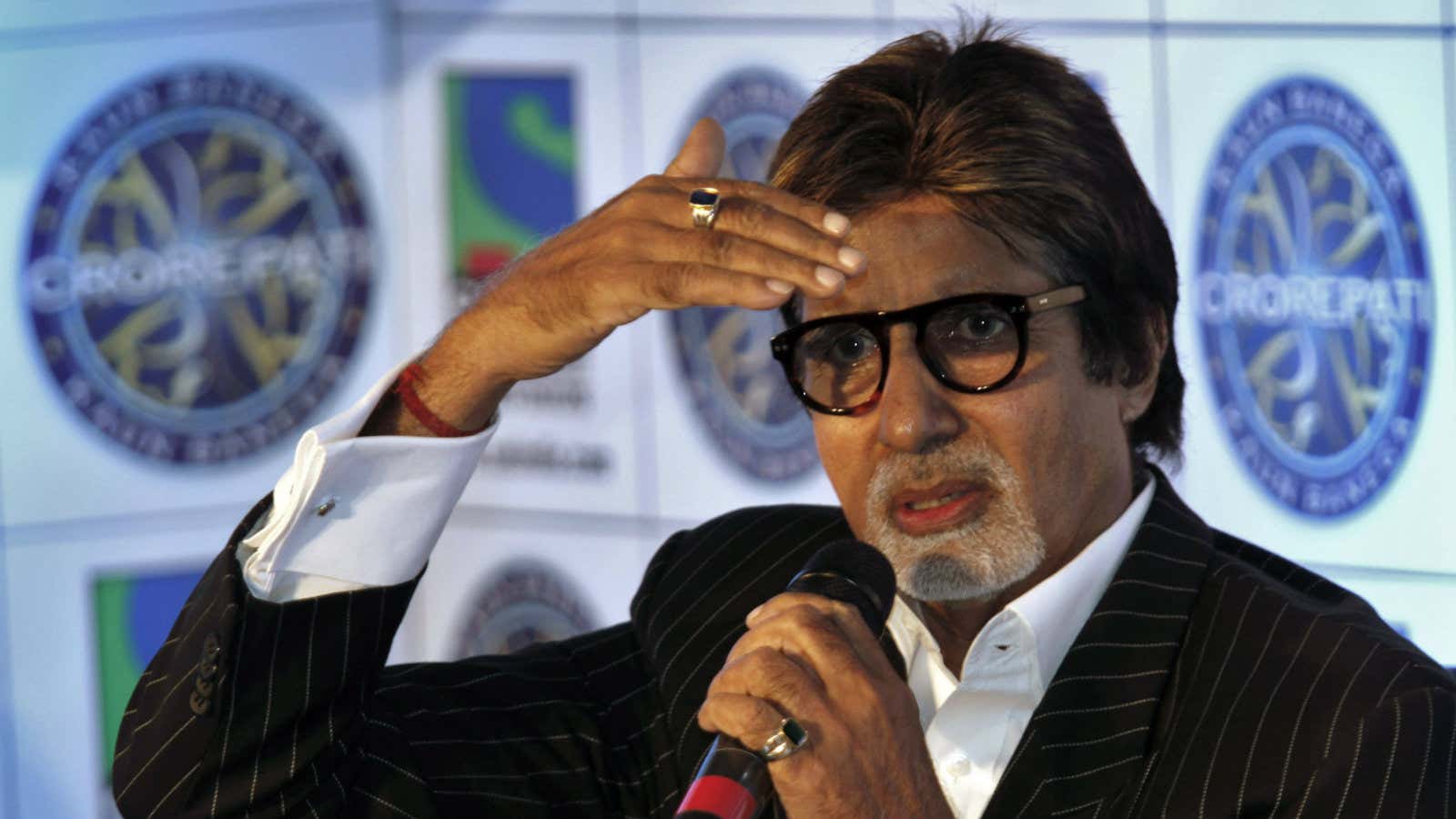

Askew, Nair and Siddhartha met in January 2000 at the Oberoi hotel in New Delhi to talk about who would host the show. For Nair, “Amitabh Bachchan was the only choice.” India’s biggest superstar at the time was fifty-seven and on the wane.

His films had been flopping and he had no connect with a new generation of Indians. Still, his was a name almost every Indian knew. “When he said ‘Bachchan,’ I said perfect—bilingual eloquence, gravitas, mass connect. At that time there were only two icons: (cricketer) Sachin Tendulkar and Amitabh Bachchan. And the formula for non-fiction game shows was cheap and simple. Using Bachchan was to signify scale,” says Siddhartha.

“Scale” was a word that would keep coming back as Star reinvented itself as a fully-Hindi, fully-local broadcaster. Bachchan was a way of announcing that.

(CEO Peter) Mukerjea’s brief to his marketing team perfectly captured what Star was attempting: “Think of it as an Indo-Pak one day international (cricket) final; that is the kind of impact I want.”

An India–Pakistan cricket match usually brings India to a standstill. The rivalry between the two nations has run deep ever since they were cleaved into separate countries from the same land mass in 1947. It has the kind of nation-stopping impact of a political assassination or that the Super Bowl had in the American market in those days.

This was a make-or-break moment for everyone at Star TV.

“We needed to pull together one show that worked across all audience groups, all socio-economic groups and several languages and do it quickly. There wasn’t a drama, a soap, a serial or a chat show that could do that. When you look at that kind of brief, you had to find the common denominator across that delivers audiences from kids to grandparents,” said Mukerjea of the task his team faced in 1999.

While they were still talking, late in February 2000, Rupert Murdoch, chairman of Star TV’s parent firm, News Corporation, came to town after four long years. And in a meeting that has now become part of corporate legend, he changed everything.

[…]

Murdoch’s insight

The meeting was going badly. Star TV’s India office was presenting a review of its business to Murdoch.

The first chart shown by Nair had partner and rival Zee as the No. 1 channel with a 7% audience share, followed by Columbia Tristar’s Sony. Star Plus, News Corp’s flagship channel in India, was a distant No. 3 with a minuscule 2% viewership share going by TAM Media Research, the ratings body.

Seven years after Murdoch had bought Star TV and poured over $1.5 billion (Rs10,300 crore at current rates) into the promise of China and India, this was dismal stuff. Especially for an aggressive, ambitious media mogul running a $14 billion empire that owned some of the world’s largest newspapers and TV stations.

Murdoch hammered his hand on the table with, ‘Oh my gawd! I never want to see this chart again.’

Nair moved quickly to the next point in the presentation. Star Plus was going to become an all-Hindi channel after the break-up of a joint venture with Zee that had restricted Star from doing Hindi programming.

The big show that would lead this change was the Indian version ofWho Wants to Be a Millionaire. Since Indians counted in lakhs and not millions, the show was to be called Kaun Banega Lakhpati.

[…]

“Are you doing the real thing or a rip-off?” asked Murdoch.

It was the licensed version of the hugely successful British show, said Steve Askew. “How much are you giving (as prize money)?” asked Murdoch.

“One lakh rupees,” said someone.

“How much is that?”

“That is $2,133,” came the answer.

“That is pathetic, it is nothing; what is the largest amount of money I can dream of winning?” he asked.

“A crore,” said Nair.

A crore, or Rs10 million, is a huge amount of money for anybody in India, even today. Murdoch wanted to know how much that was.

“That is about $2,13,310,” said someone. The bean counters in the room were beginning to fidget by now.

“Make it a crore then,” said Murdoch, picking up his jacket.

Right move

“That single decision is at the heart of where Star is today. It wouldn’t have changed the industry the way it did if that hadn’t happened. And Rupert doesn’t get credit for that,” says Ajay Vidyasagar.

“Those few minutes is what made Star. Somebody had the guts and vision to ignore the prepared presentation,” agrees Kaushal Dalal.

Making Kaun Banega Lakhpati into Kaun Banega Crorepati (KBC) did not just treble the budget of the show, it changed the nature of the TV game in India. It meant announcing loudly, emphatically that Star was local, Hindi and very Indian. It meant using the Bachchan charisma to funnel audiences to Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi and Kahaani Ghar Ghar Kii.

It meant ruling the airwaves for six long years. And it meant that Star became one of the largest media companies in India—largely on the back of the head start given by KBC.

Excerpted from Vanita Kohli-Khandekar’s The Making of Star India with permission from Penguin Random House India. We welcome your comments at [email protected]