One of Narendra Modi’s biggest policy initiatives in his first term was Swachh Bharat, the Clean India initiative. It helped Modi build his image as a statesman who looked at the big picture—as well as win votes by building toilets for millions across India.

How was this initiative funded? Using a cess: the Swachh Bharat cess came into being in 2015 as part of a 0.5% levy on services. If you take out a restaurant bill before the new Goods and Services Tax (GST) came into effect, you will be able to see it as a separate line item.

And while the GST was supposed to usher in a “one nation, one tax system,” cesses are still clinging on. In fact, they are thriving. In the latest budget, the Modi government has hiked the cess on petrol and diesel. A close cousin of the cess, the surcharge has also been used as a way to better tax the super rich.

Once an arcane part of fiscal policy, cesses are now playing an increasingly significant role in how the union government raises money.

A cess is simply a tax earmarked to a particular purpose. So, in theory, the Modi government can’t spend the Swachh Bharat cess on, say, buying defence equipment. It is also typically imposed as a tax on tax—the Swachh Bharat cess was a 0.5% add on to Service Tax. And most importantly, the union government does not have to share cesses with the states. This is something that cesses have in common with surcharges. Although unlike a cess, a surcharge does not have to be earmarked.

In India’s system of federalism, while the union collects most of the taxes, it is the states that do most of the development work. What does it mean for Indian federalism if the union government is now relying more and more on cesses and surcharges which are not shared with the states?

Fiscal squeeze

To understand why the union government would want to take the drastic step of keeping money away from the states, it would be instructive to start by looking at the state of the centre’s finances.

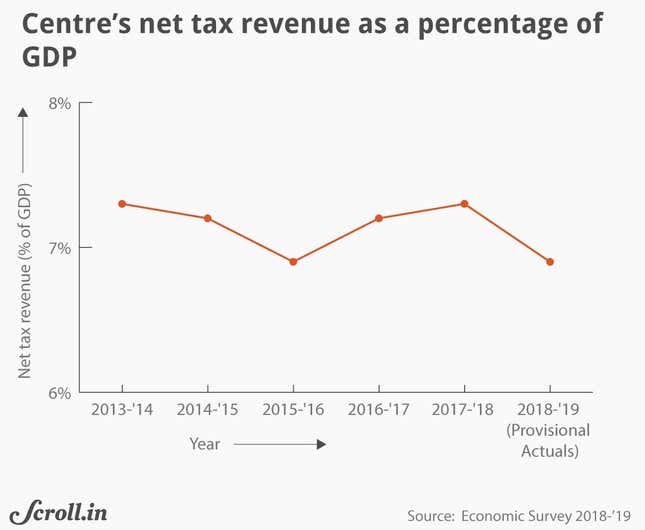

As we can see from the above chart, the union government’s net tax revenue (that is, its tax revenue once the states’ share has been transferred) has had a choppy ride over the past six years. While it was 7.3% of the Indian GDP in 2013-14, it eventually dipped to 6.9% in 2018-19.

Moreover, as Rathin Roy of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy pointed out in February, a very large proportion—more than two-thirds in 2017-18—of central government expenditure is on committed expenditure: things such as interest payments and wages, over which the government has little control. This shrinks the government’s space to manoeuvre when it comes to, say, launching a new scheme.

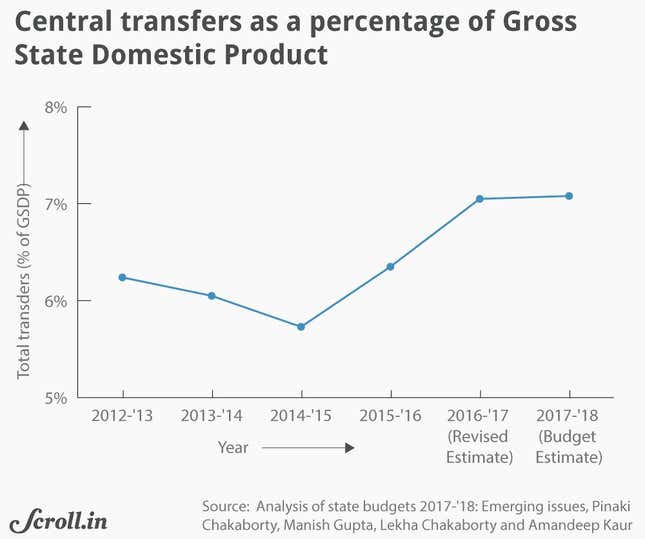

Besides, central transfers to the states actually saw an uptick thanks to the recommendations of the 14th finance commission—the constitutional body that decides how the centre and the states will share taxes. See what is happening in the chart below in the year 2015-16, when the commission’s recommendations come into play: there is a sharp spike in central transfers.

How then did New Delhi lessen this fiscal squeeze? One solution it pulled out of its hat: cesses and surcharges. Since these don’t have to be shared with the states, it partially helps the centre get out of its cash crunch.

A history

Cesses might have hit the limelight now but they have been part of the Indian state since the British Raj. The first cess in British India was an education cess on land revenue levied by James Thomason, the lieutenant-governor of the north-western provinces, now part of Uttar Pradesh. The money generated was used to set up rural primary schools.

According to extensive research by Ashrita Kotha, an assistant professor at the Jindal Global Law School, Sonipat, there have been 39 union cesses since 1950. Most of them fall within three buckets: development of a particular industry, labour welfare and general, broad-based causes.

The first type dominated from 1950 to 1980, as India endeavoured to develop indigenous industry. The Nehru government, for example, levied a rubber cess in 1961 in order to grow the rubber industry. Labour cesses (for example, a levy on mine owners for worker welfare) held sway from the 1960s to the 1980s as India took a socialist turn under Indira Gandhi. From the late 1990s, broad-based cesses came into play to finance education, hygiene and agriculture, amongst others.

No sharing

The first time it was set out that cesses would not be shared with the states was in 1965, as per the recommendation of the fourth finance commission. The logic of it was: since the purpose of the money was already earmarked, it made no sense to hand it over to the states.

By the time of the eight finance commission, which submitted its report in 1986, the problem of rising cesses had become quite acute. A number of states complained and the commission itself noted that the cesses and duties that the Union hoarded for itself stood at (pdf). While the report did not change the nature of cesses, it did suggest that they “should be kept to the minimum as it causes grievances amongst the states”–a suggestion that New Delhi cooly ignored.

In 2000, upon the recommendation of the 10th finance commission, the constitution was amended to provide, for the first time, legal backing for cesses and surcharges which would not be shared with the states.

Post this, cesses get turbocharged. Cesses are now applied not only on excise duty but also income tax (education cess) and service tax (Swachh Bharat cess).

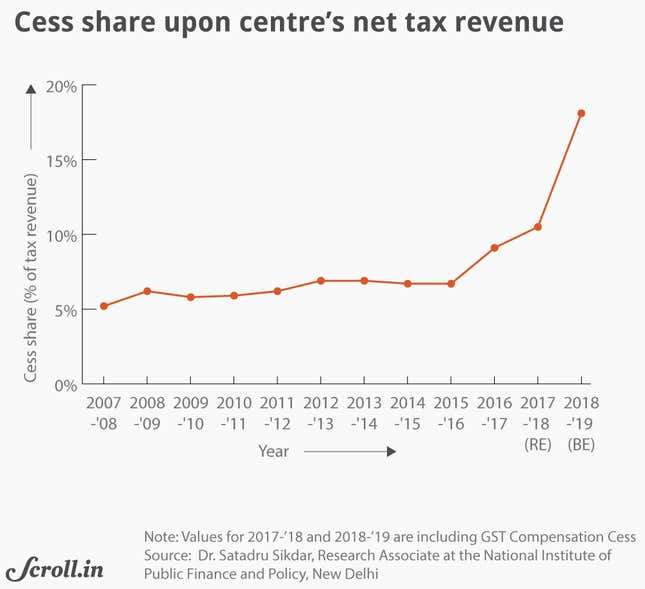

As can be seen above, cesses rise steadily from 5.2% of the union’s net tax revenue in 2007-08 to 6.7% in 2015-16. This number sees a further spike in 2016-17, a year after the 14th finance commission recommends a higher tax devaluation to the states. And it sees a large jump in 2017-18 and 2018-19 as the GST Compensation cess kicks in to compensate states for tax revenue lost as a result of the new GST regime.

Note, however, that by now the initial logic that actually allowed the centre to not share cesses with states is gone: cesses are not being earmarked to particular purposes anymore even though they are still called cesses by the Union government.

“It turns the initial rationale of cesses on its head,” said Kotha.

Red Flags

Given this sudden prominence of cesses in union finances, a number of alarms have been raised by experts.

The biggest concern is the impact on India’s federal structure. “Since the revenue from cesses is not shared with the states, this might have a negative impact on India’s structure of fiscal federalism and curb the fiscal space of state governments,” explained Satadru Sikdar of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

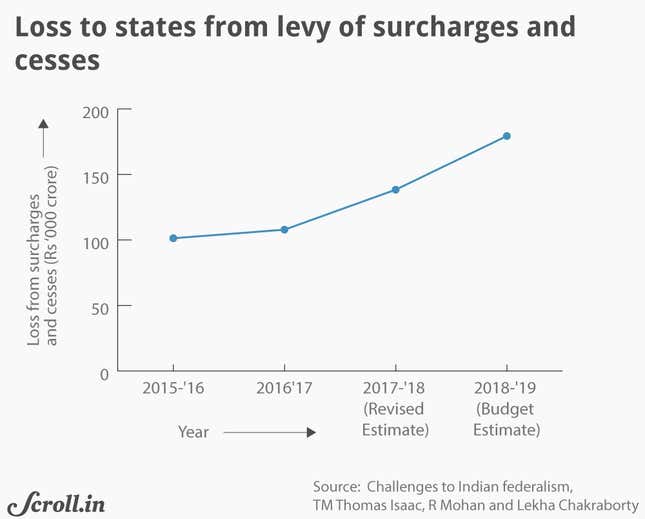

Sikdar’s point is borne out by the data. As can be seen from the chart below, the states are losing a significant amount of money with the imposition of cesses by the Union government.

In the union budgets since the 14th Finance Commission, argue TM Thomas Isaac, R Mohan, and Lekha Chakraborty in their book Challenges to Indian Federalism, “surcharges and cesses are being used as mechanisms to shrink the divisible pool of taxes and compensate the Centre for the perceived loss of revenue due to enhanced devolution.” In the 2017-18 union budget, for example, even as the rate of income tax was reduced, a new surcharge was added since only the former need be shared with the states.

This is a continuation of what Justice MM Punchhi, who headed a commission on centre-state relations in India, had described in 2010: “Extension of cesses and surcharges amounts to dilution of the recommendations of the Finance Commission and deprives the States of their due share of tax revenue.”

However, the damage done to the federal structure is not only limited to the fiscal side. Interestingly, the union government has also used cesses as a tool to enter the administrative domain of the states as defined in the Indian constitution. “Using cesses on agriculture (Krishi Kalyan cess) and sanitation (Swachh Bharat cess), the union is entering domains that are a part of the state list,” explained Kotha.

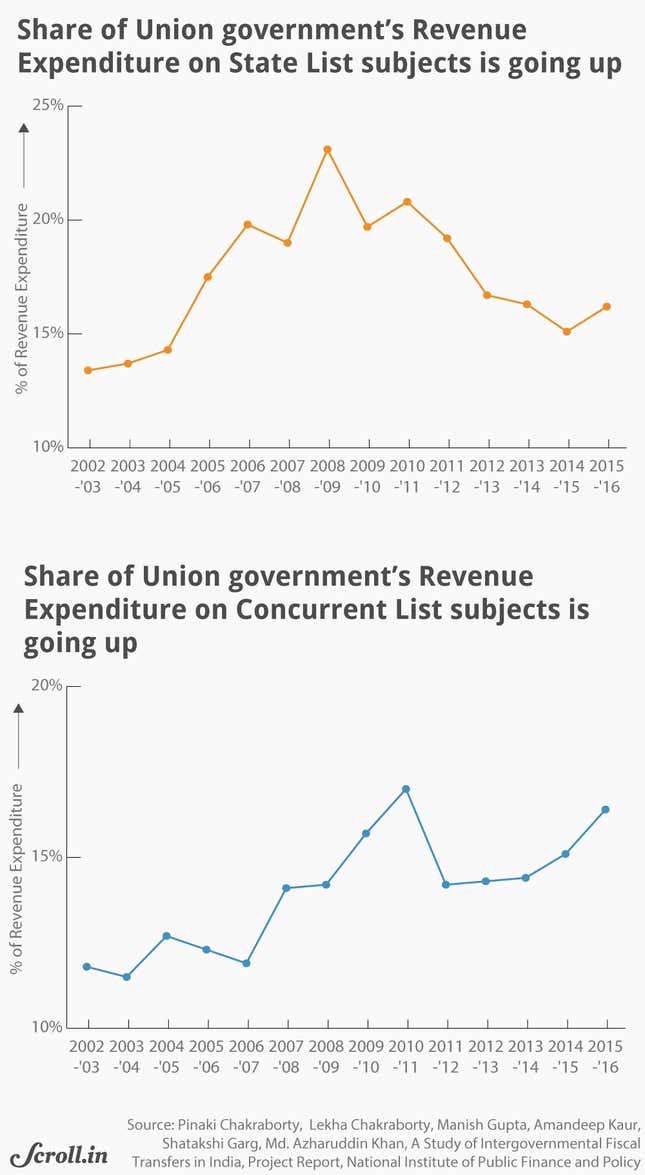

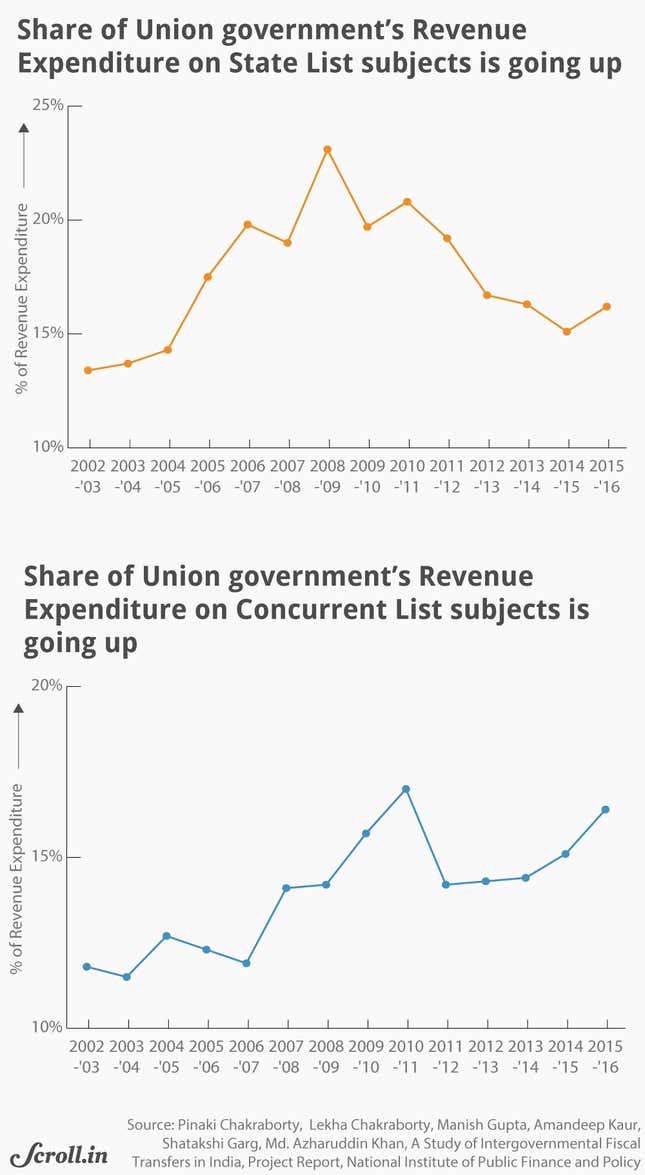

This intrusion of the union into the domains of the state government has been fiscally mapped by Pinaki Chakraborty at the national institute of public finance and policy. Between 2002-03 and 2015-15, central spend (as a proportion of its revenue expenditure) on state list subjects went up from 13% to 16%. The equivalent expenditure on concurrent list subjects (a constitutional domain shared by New Delhi and the states) went up from 11.8% to 16.4%.

Another concern is that cesses are not being used for their earmarked purpose and being diverted to other commitments. The 2013-14 report of the Comptroller and Auditor General noted that only 11.12% of the amount collected under the Research and Development Cess from 1996-97 to 2013-14 was used for research and development. Of the remaining funds, some were even used to finance the revenue deficit of the union government.

More worryingly, cesses are simply not being earmarked to begin with. The Swachh Bharat cess, for example, had an ambit that was so wide it was difficult to pin down to a specific, earmarked task. Some part of the Swachh Bharat cess was spent not on sanitation but on advertisements. Moreover, Kotha notes that the GST compensation cess is simply not earmarked but the amount transferred to states. “One state could build a road with it, the other could spend it on salaries,” she explained. “How does this fit the definition of a cess anymore?”

Lastly, having such a multiplicity of tax heads is a recipe for inefficiency. This point has even been made by the Modi government itself as it repelled 13 cesses in 2016.

Ironically, the GST regime was meant to do away with multiple taxes under the Modi government’s “one nation, one tax” mantra. However, as is clear from the spike in cesses, they now occupy a greater prominence than ever.

Curb cesses

Given how cesses impact Indian federalism, for some time now, experts have been advocating that their use be curbed. As far back as 1983, the Sarkaria commission had recommended that cesses “should be for a limited duration and for specific purposes only.”

In 2019, TN Thomas Isaac, R Mohan and Lekha Chakraborty suggested that cesses that continue for more than two years should compulsorily be shared with the states and a constitutional amendment be passed to reflect this arrangement.

Kotha recommends a further cutting down of the inflated role of cesses, suggesting that it only be applied by local government, as it was in British India given that in that case the “the implementing authority is better equipped to understand the needs of the concerned communities” and it will truly function as an earmarked tax.

However, this expert opinion needs to be seen against the 2019 general election results, where multiple states voted for a strong national party which is also ruling at the Centre.

While expert opinion might be ranged against monies which the Centre can keep from the states, will the political economy of the current Indian union–where the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) rules both in New Delhi and 16 states – allow for even this minimum degree of fiscal federalism?

This piece was first published on scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].