Nirav Modi did not leave Belgium as a successful entrepreneur, nor did he have any kind of work experience with top Western jewellery houses. While it’s not clear what he intended to do when he returned to India, what is certain is that by around 1999 Nirav Modi had arrived in Mumbai and begun his tutelage under Mehul Choksi.

Why did he not, instead, join hands with his other uncle, Chetan Choksi, who was already in Europe? The answer is that there wasn’t much love lost between him and Chetan. Aside from his rapport with Mehul, another factor may have motivated his return. India was at a crossroads after the liberalisation of its economy. The future was wide open and for a young entrepreneurial expatriate who had returned to start with the support of an entrenched player, India was a land of endless opportunities.

Once the die was cast, Modi learned how gems and jewellery worked in India. What he learned he would, in turn, pass on to his brother Nishal, including how to work within tight budgets and how to buddy up to mid-level employees in factories by sipping on cutting chai with them during breaks.

Modi has claimed that he had always planned for a luxury brand, but during the years that he was with his uncle, and shortly after, he was building up businesses of the diamond supply chain that were of lower-value and that included polishing and trading. But it was fluting, essentially the manual bagging of diamonds for other manufacturers, that gave his company the launch pad it needed, or so Modi would declare publicly.

Modi first called his company Firestone, but then changed it to Firestar in 1999 because the former sounded too much like the automotive tyre company. In Modi’s own words, the company gave him consistent profits for the better part of five or six years and, by 2004, Firestar’s revenues crossed Rs400 crore ($56.5 million).

However, when others got into the game and competition stepped up, the margins he was making in the fluting business evaporated. It was then that he looked to maximise his footprint in manufacturing and distribution. After all, monster-size margins only came into the picture once a jeweller got into retail and then branding, followed by the luxury segment.

In 2005, he bought a retail division owned by Frederick Goldman, an American diamond retailer with a nationwide footprint. Two years later he bought Sandberg & Sikorski, the largest jewellery supplier to the US Armed Forces, as well as A Jaffe, a 120-year-old luxury bridal jewellery label that Sikorski owned.

Its promoter Samuel Sandberg retained a 5% stake in the firm, and had Modi supplying diamonds and jewellery to department stores like Costco, JCPenney and Zales. A Jaffe’s only business was to make and sell bridal jewellery and while it did buy loose diamonds it didn’t keep diamonds as inventory or sell loose stones, let alone in bulk.

When it was first bought, A Jaffe’s revenues were sluggish, at between $6 million and $7 million a year and the firm was struggling to make profits. However, in due course, the company saw growth with as much as $20 million sales a year. The extra gravy was cash from loose trades. While the business involved standard contracting jobs that would get outsourced to Indian jewellers, in Modi’s case it was a means to an end: building his business slowly but surely to get his finger into every single aspect of the diamond trade.

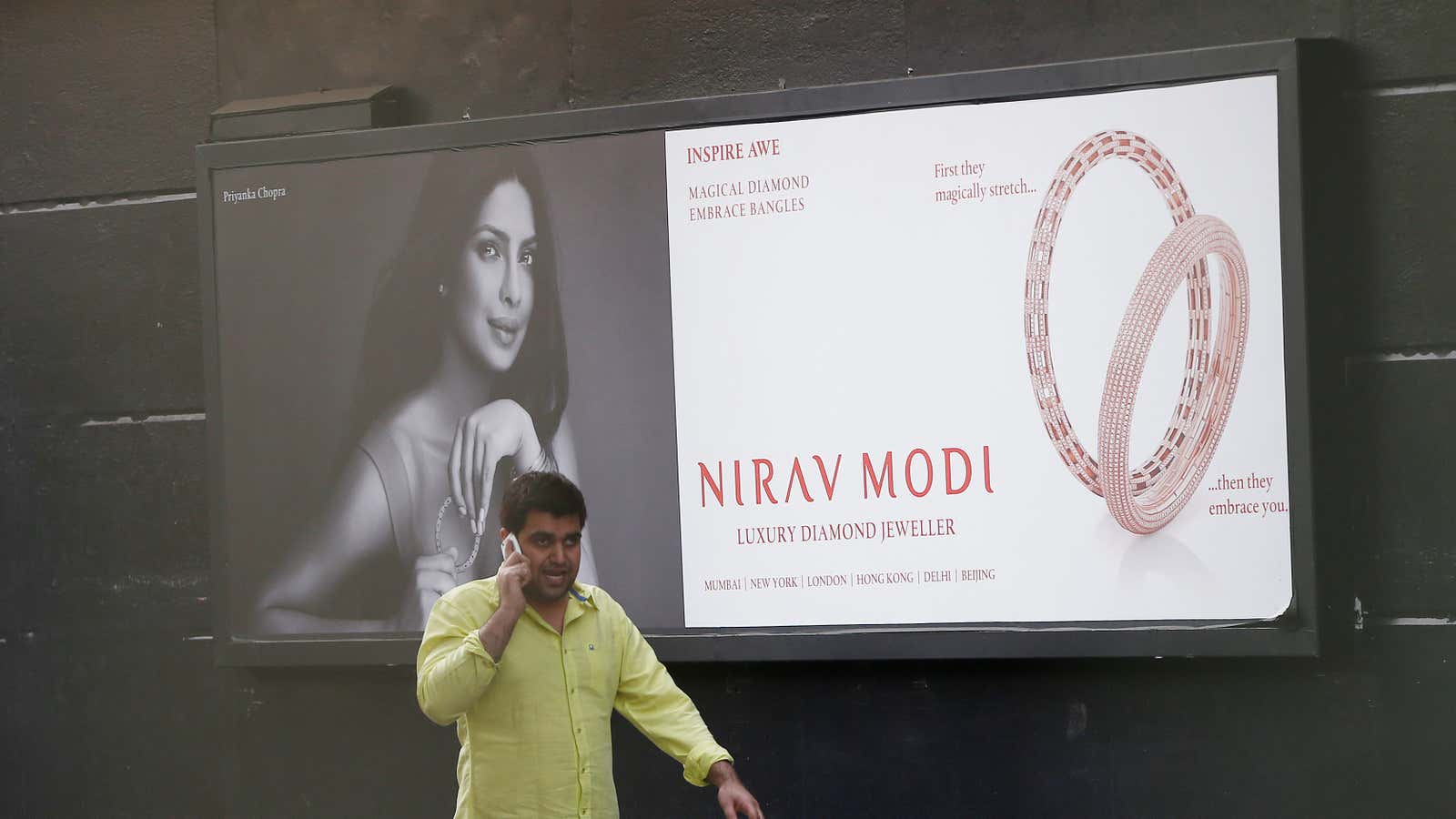

Besides the fatter margins that lay higher up on the value chain in designer jewellery and retail, the other upside for Modi was to see his name lighting up on billboards across the world, later even on Madison Avenue. The margins that come with luxury retail work like this: it’s 2.5% on diamond trading, between 5% and 7% on wholesaling, and anywhere between 15% and 25% and upwards on retail.

By 2015, with the addition of these assorted businesses, Modi would report that his revenue had crossed Rs10,000 crore, with average margins at around 3.6%.

“Are you a trained jewellery designer?” I asked Modi some time in 2015 during a meeting for a Fortune India interview at his office in Worli.

“No,” came the answer as he shifted in his seat.

“A professionally trained artist then?”

Another “No.”

Was he someone with an eagle eye for great stones and a dyed-in-the-wool knack for “rough” trading, which drove the bulk of his revenue?

Yet another “No,” followed by a reference to his younger half-brother, “That’s Nishal’s thing.”

If design was handled by his sister Purvi Modi-Mehta in Hong Kong, and finance by CFO Vipul Ambani, what then did Modi do, apart from just lending his name to the brand? Turns out, plenty. For starters, he created the brand. Then he took all the wild gambles, speeding the train forward while the other family members assumed charge of more sedate corporate functions, though all under his direction.

Nirav Modi was the undisputed boss of the family, says one jeweller who knows Modi well. “Everyone, including his parents and siblings, worked for him and took orders from him.”

Modi, who ran the flagship company, Firestar International Private Limited, may have been nephew to Gitanjali Gems’ boss Mehul Choksi, but what is not commonly known is that Modi’s sister Purvi Modi-Mehta is married to Mayank Mehta, Rosy Blue’s boss Russell Mehta, through being brother to Russell’s wife Mona.

Again, Mona’s first cousin is Preeti Choksi, or the wife of Mehul Choksi, Modi’s uncle, and Choksi’s daughter Priyanka wed Antwerp-based diamond merchant Akash Mehta in 2011. At the time, Priyanka Choksi was running the jewellery company A Jaffe, which her cousin Nirav Modi had invested in.

Modi was also the architect of the eponymous brand right from its marketing and inception to overseeing product development and customer relations.

While he kept books on Harry Winston, Joel A Rosenthal and Bvlgari on his office mantelpieces, as well as at home, he would agree that his plans most resembled those of diamond king Laurence Graff, the founder and chairman of Graff Diamonds, a company launched over half a century ago that had gilded its reputation by purveying large, rare gems to celebrity clients ranging from Elizabeth Taylor to Oprah Winfrey to Donald Trump. Graff never finished school but instead became an apprentice to a jeweller.

In due course, he went on to start his own brand that targeted high net worth clients. He launched dozens of stores across the world and even picked up a stake in a diamond mine to complete the supply chain internally for his company. Beyond business, Graff also has a passion for art with a collection that includes Warhols and Picassos.

The parallels between Graff and Modi are apparent. Like Graff, Modi too never completed college and, with the exception of mines, owned and operated other parts of the diamond value chain, including retail, wholesale, cutting and polishing, trading of roughs and private label manufacture for other companies.

The key difference between Modi and other jewellery bigwigs like Bvlgari, Harry Winston, Cartier, Tiffany’s, and Van Cleef & Arpels was, of course, that they had begun their journey over half a century ago—and had burnished their luxury synonymous names over time with millions of customers and celebrity endorsers who sported their wares because they wanted to and not because they were being paid to do so.

Modi, on the other hand, was pushing the needle from trading to luxury in just a little over a decade.

Excerpted from Pavan C Lall’s Flawed: The Rise and Fall of India’s Diamond Mogul Nirav Modi with permission from Hachette India. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.