India’s global competitiveness has fallen for the third year in a row.

The country has slid 10 places on this year’s global competitiveness index, “an annual assessment of the drivers of productivity and long-term economic growth” released by the Geneva-based World Economic Forum (WEF). India now ranks 68th out of 141 economies. This year, Singapore overtook the US as the world’s most competitive economy.

The rankings roughly correlate with the countries’ average income levels. India’s rank had improved during the early years of prime minister Narendra Modi’s government, to the evident joy of his administration. But it has steadily fallen since then.

In 2017 and 2018, WEF attributed the decline to a change in its methodology. But the organisation has not made a clarification for India’s worsened performance this year.

All in the workplace

In a subset of the rankings, India’s labour market fell 28 places to 103 this year. “The labour market (in India) is characterised by lack of worker rights’ protections, insufficiently developed active labour market policies, and critically low participation of women,” the report said.

The Modi government, which kicked off its second term this year, has proposed to reform India’s archaic labour laws and improve business conditions for companies. The reforms are expected to weaken some of the legal protections accorded to workers. With Modi’s party eyeing a majority in both houses of parliament, amending the existing laws is likely to become less painstaking.

At rank 128, India’s ratio of female to male workers (both salaried and otherwise) is among the worst in the world. While more and more Indian women are getting higher education, their share in the workforce isn’t rising proportionately, at least partly due to the cultural pressure on many women to be homemakers.

Ranked 107th, India’s workforce is also among the least-skilled even though the country has some of the best innovation capabilities, ranked 35th in the world. While many Indians are at the forefront of technological advancement, a majority of the country’s labour force is being left behind. This begins as early as in primary school, where there are an average of 35 students for every teacher, WEF notes in the report.

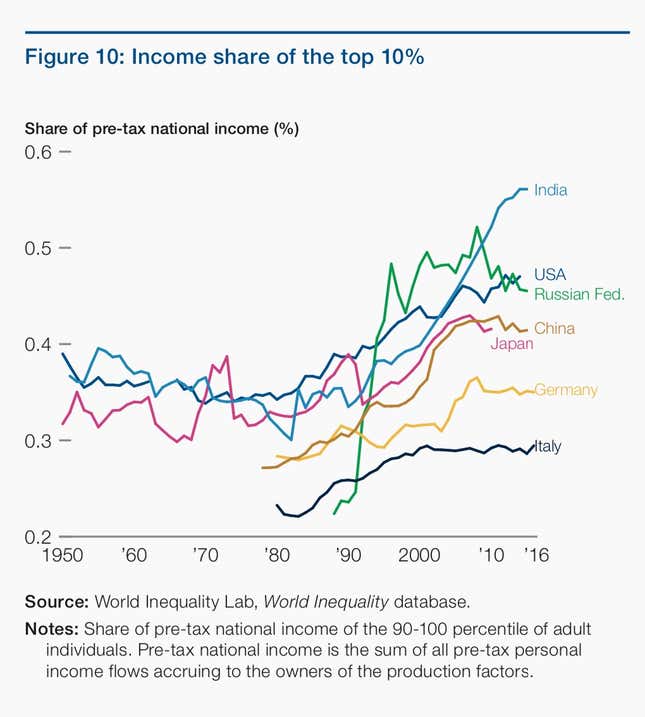

India’s crumbling public education system and low social mobility also contribute to income inequality in the country, which has shot up in only the past few years.