For the last few years, India’s Bharatiya Janata Party-led union government has insisted that all is well with India’s economy and that it remains among the fastest growing in the world. But revised projections for India’s GDP growth rates this year alone indicate otherwise.

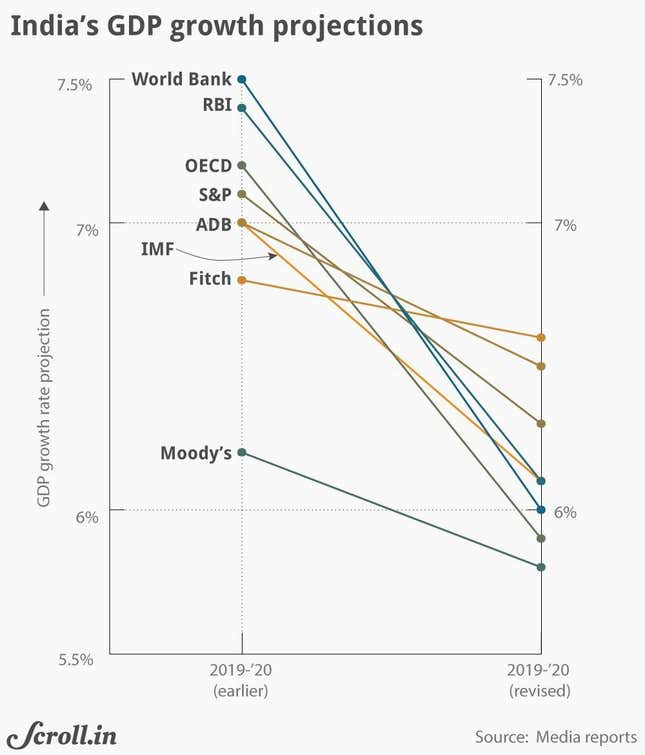

In fact, some analysts have dropped growth projections for 2019-20 from 7.5% all the way to just 6%.

The bad news started to pour in after India’s GDP growth rate slipped to a six-year low of 5% in the April-June quarter, and the government finally admitted that the economy was slowing. On Oct. 15, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) slashed India’s GDP growth rate projections to 6.1% from the 7% it forecast in July, The Hindu Businessline newspaper reported.

While trade tensions between the US and China have also hurt the Indian economy, the IMF stated that India’s “governance of public sector banks and the efficiency of their credit allocation needs strengthening,” according to the report.

A few days earlier, the World Bank, on Oct. 13, had cut India’s GDP growth for 2019-20 to 6% in its latest South Asia Economic Focus report. “India’s cyclical slowdown is severe,” the report states. It also projected 6.9% as the growth rate for 2020-21, and 7.2% for 2021-22.

In April, the World Bank had forecast a growth rate of 7.5% for India, but in 2018 it pegged the rate lower at 6.8%.

Multiple indicators

The IMF and the World Bank have not been the only institutions to sound the alarm bells for India’s economy.

Their assessment comes after the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the country’s autonomous central bank, trimmed India’s growth rate projection to 6.1% on Oct. 4 for 2019-20. This came after the RBI approved a transfer of Rs1.76 lakh crore ($25 billion) of its reserves to the central government on Aug. 26.

But the central bank indicated a sluggish pace in the economy much earlier as it kept slashing its projections for 2019-20. It started off with 7.4% in February. This figure fell by 0.2 percentage points to 7.2% in April. The figure gradually decreased in June and August, before coming down to 6.1% when the RBI made its latest revision.

The indicators from other rating agencies started to come in June when Fitch Ratings cut India’s growth rate projections to 6.6% from 6.8%.

A few months later, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) was also one of the institutions to sharply cut down its forecasts for India. It narrowed it down to 5.9% on September 20, a reduction by 1.3 percentage points from its previous projection in May.

On September 25, the Asian Development Bank slashed India’s growth projection to 6.5% from 7% in July. It also projected an increase in India’s growth rate for 2020-21 at 7.2%, attributing it to the “proactive policy interventions along with a recovery in domestic demand and investments.”

On Oct. 1, another rating agency, Standard and Poor’s, slashed India’s ratings and stated that the country’s slowdown was “deeper and more broad-based” than what it expected, adding that there were more signs of caution. It projected India’s rate at 6.3%, a reduction by 0.8 percentage points from its previous prediction for 2019-’20.

On Oct. 10, credit rating agency Moody’s Investors Service had trimmed India’s growth rate down to 5.8% from 6.2% for 2019-20. It forecast that the rate would pick up to 6.6% in 2020-21.

Falling economy

The Indian economy has been plagued by several challenges. Some of these include non-banking financial corporations (NBFCs) running into trouble in 2018, hurting lending services to residents of smaller Indian cities seeking credit to buy homes and vehicles. This is also one of the reasons for the slowdown in the automobile sector.

Several analysts have also attributed this slowdown to a decline in consumption, investment and exports.

In addition, the Union government is facing a severe cash crunch because of the falling tax revenue under the Goods and Services Tax (GST) mechanism.

Amid clear signs of an economic slowdown, union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman on Sept. 19 announced tax cuts for domestic companies from 30% down to 22%. The hope was that the new rates would increase the profit margins of domestic companies leading to more investment and economic activity.

But less than a month later, the euphoria around the tax cuts died down as stock prices of several listed firms on BSE were back to the old levels.

This story originally appeared on Scroll.in.