The Himalayan Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), the scene of terrorist violence for decades and one of the world’s most militarised regions, ceases to exist from today (Oct. 31).

The 200-year-old state officially bifurcates into two Indian union territories—J&K and Ladakh—which will be administered from New Delhi. Senior bureaucrat Girish Chandra Murmu will take oath later in the day to be the first-ever lieutenant governor (L-G) of J&K, while Radha Krishna Mathur, another bureaucrat, will be sworn-in as Ladakh’s new L-G.

This marks the downgrading of the former kingdom’s status from one of the 29 (now 28) Indian states to one of its nine union territories now. With this, J&K also loses its relative autonomy from the Indian government, it’s separate flag, and a constitution.

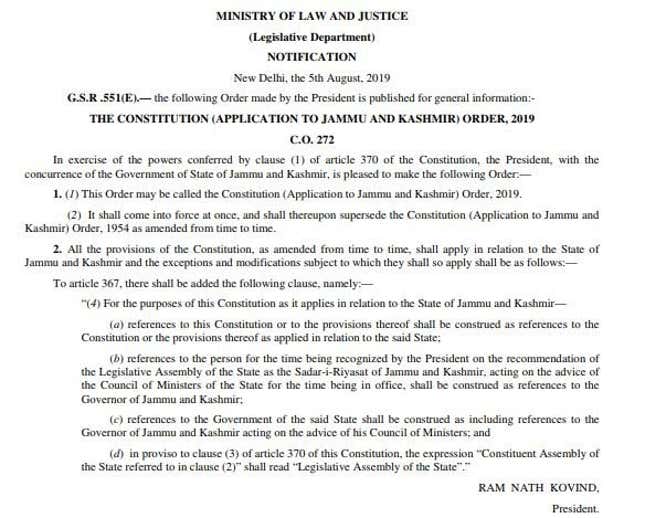

This former arrangement was the condition under which J&K, under its late king Hari Singh, acceded to India following the subcontinent’s independence from British rule. On Aug. 5 this year, the Narendra Modi government rendered Article 370 of the Indian constitution, which formed the bedrock of this autonomy, ineffective through an amendment in parliament.

“We are adopting the same path as adopted by the Congress in 1952 and 1962 by amending the provisions of Article 370 the same way through a notification,” Indian home minister Amit Shah had told the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian parliament.

Since this dramatic move, J&K has been placed under a massive clampdown fearing an uprising. The communication blackout, heavy deployment of security forces, and a never-ending curfew have been making international headlines.

The new L-G’s focus will now be ensuring the return of normalcy following the over 80-day long restrainment. The Muslim-majority region has already suffered from war—between Indian and Pakistan—terrorism, and military high-handedness for close to seven decades now.

With J&K administration ending the house arrest of top state leaders after two months, here is a recap of some key developments that have put the spotlight on the plight of the people of Kashmir.

A contentious visit

On Oct. 29, an international delegation constituting some members of the European parliament visited J&K. This was a private event, not an official one.

Of the team’s 27 members, mostly from the far-right parties, four dropped out earlier. One of those who dropped out, Liberal Democrat Chris Davies, said he changed his plan because he wasn’t allowed access to people and places in Kashmir for a fair assessment.

“I am not prepared to take part in a PR stunt for the Modi government and pretend that all is well. It is very clear that democratic principles are being subverted in Kashmir, and the world needs to start taking notice,” Davies said.

Yesterday (Oct. 30) after the completion of their visit the delegation extended its support to India. “This visit has been an eye-opener and we would definitely advocate what we have seen on ground zero,” said Newton Dunn, a lawmaker from the UK.

The MPs also met the Indian prime minister on Oct. 28.

The Indian National Congress’s Rahul Gandhi, however, slammed the government over its decision of not allowing the country’s own opposition leaders to visit the state but entertaining foreign leaders.

On Aug. 24, the government stopped a delegation of Indian MPs from opposition parties, led by Gandhi himself, from entering J&K at the airport in capital Srinagar. The team wanted to assess the situation after the Aug. 5 announcement.

No end to violence

The European Union parliamentarians visited J&K on a day when five labourers from the state of West Bengal were killed by terrorists in J&K’s Kulgam district.

This wasn’t the first such incident though. The spike in killings of truck drivers and apple traders from outside Kashmir by terrorists has kept even local farmers anxious of late.

Contrary to the government’s claims of “peace” in J&K, close to 300 incidents of stone-pelting have been reported in the past two months. There have also been reports of shootouts by security forces.

Since 1947, ethnic strife and terrorist attacks have resulted in hundreds of thousands of lives lost in the region.

UN, other global bodies appeal for human rights

The United Nations on Oct. 29 expressed its concerns over violations of human rights in Kashmir.

“We are extremely concerned that the population in Kashmir continues to be deprived of a wide range of human rights and we urge the Indian authorities to unlock the situation and fully restore the rights that are currently being denied,” Rupert Colville, spokesperson for the UN high commissioner for human rights, said on Oct. 29.

Human rights organisation Amnesty International, too, launched a campaign in September to end the blackout.

When will Kashmir speak?

India has justified the communication blackout in J&K on various grounds.

On Sept. 22, Indian Army chief, Bipin Rawat, claimed that despite the suspension of telephones, there was “no communication breakdown among people” in J&K.don’t agree there is a clampdown. The brick kilns are active. Smoke is seen coming out of the chimneys. Sand is being collected from Jhelum river,” Rawat said.

The government recently allowed only postpaid phone connections to be resumed. Internet services, too, have been shut for the 87th straight day.

Earlier, when asked when the communication will be fully stored in the valley, the government spokesperson said: “There continues to be tremendous provocation from across the border. Any decision on restoring mobile services will have to factor it in also.”

Other countries react and here’s how India replied

The ties between India and Malaysia have come under stress over Kashmir.

In a bid to support Pakistan’s stance at the UN last month, Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad criticised India for “invading and occupying the country of Jammu & Kashmir.”

In his address to the 74th UNGA, Mohamad said: “There may be reasons for this action but it is still wrong. The problem must be solved by peaceful means. India should work with Pakistan to resolve this problem. Ignoring the UN would lead to other forms of disregard for the UN and the rule of law.”

However, these comments have not gone down well with India. Indian traders have called for a boycott of Malaysian palm oil, of which India is the third-biggest market.

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, too, has talked about resuming talks between India and Pakistan so that the Kashmir issue could be settled. “In order for the Kashmiri people to look at a safe future together with their Pakistani and Indian neighbours, it is imperative to solve the problem through dialogue and on the basis of justice and equity, but not through collision,” he said.

Meanwhile, US president Donald Trump has offered to mediate between India and Pakistan on the condition that both the countries agree for the same. On Oct. 22, the US House foreign affairs committee held a hearing on human rights in south Asia, debating the situation in the state.

Many other countries, meanwhile, have avoided getting drawn into the controversy. This includes India’s neighbours Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. On the other side, the UK has expressed concerns over the situation but has maintained that Kashmir is a bilateral matter between India and Pakistan.

Overall, the Kashmir imbroglio has received considerable international attention since Aug. 5, a situation that India, which deems the issue a strictly bilateral one, has avoided for decades and Pakistan has sought desperately.

Pakistan’s “concern”

As expected, Pakistan has been vocal about its displeasure over India’s Kashmir gamble.

Since the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, the country had refused to recognise the accession of J&K with India, making multiple failed bids to militarily seize the region—1947-48, 1965, and 1999.

In his UN speech in September, Pakistan prime minister, Imran Khan, warned against a “bloodbath” in Kashmir once India lifts the curfew. In its response, India reiterated its stand that the country “does not need anyone else to speak on its behalf.”

This, though, did not stop Pakistan from lashing out more against India. On Oct. 29, Pakistan’s minister for Kashmir affairs and Gilgit Baltistan, Ali Amin Gandapur, warned of a nuclear attack against India and countries supporting its stand.

“If tensions with India rises on Kashmir, Pakistan will be compelled to go to war. Hence, those countries backing India, and not Pakistan (over Kashmir), will be considered as our enemy and a missile will be fired at India and those nations supporting it,” he said.

These chilling comments from a high official of that country once again put the spotlight on the nuclear risks involved in south Asia, especially with regards to Kashmir.