Sanjay Kumar Hansda, a member of the Santhal tribe, would usually earn as much as Rs25,000 ($331) between March and June by collecting and selling minor forest products. However, this year, the prospects look rather bleak.

Until now, early May, his earnings have plummeted by 70% from the usual due to the ongoing lockdown in India. “I used to collect and sell mahuwa, karanj seed, tamarind and other forest products in the market but this year no buyer has turned up in our area. Whom should I sell all this to now?” questioned Hansda, who lives in Jashipur Block of Mayurbhanj district in Odisha.

The countrywide lockdown imposed to prevent the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic has impacted the livelihood and economy of indigenous people living in and around the forests of India. The collection and sale of hundreds of minor forest products (MFPs), which form the backbone of forest dwellers’ economy, are badly affected. This is despite the lockdown relaxation announced by the central government on April 17 for harvesting and processing of these forest products. It is estimated that every year the tribal people and forest dwellers collect Rs2 lakh crore worth of non-timber forest products (NTFP) from the country’s forests.

“The lockdown relaxation is for the people living in these (tribal) areas, not for the traders and contractors. For the traders to come and operate (collect and purchase the MFPs), they need to bring vehicles like trucks with them to transport the (forest) produce. That is why there is a lot of confusion and it has hampered the season this year,” said Y Giri Rao, director of Vasundhara, an NGO that closely works on forest dwellers’ livelihood issues.

NTFP and MFPs have a major role in the economy of the tribal societies. According to the government’s own admission, “Around 100 million forest dwellers depend on MFPs for food, shelter, medicines and cash income.” Across the country, there are more than 200 recognised minor forest products including tendu leaf, bamboo, mahuwa (flower and seed), sal (leaf and seed), lac, chironjee, tamarind, gum, and karanj seed.

As per the data of Tribal Co-operative Marketing Development Federation (Trifed), an arm of the ministry of tribal affairs, the total estimated value of only 55 forest products is Rs20,000 crores. It is estimated by the government that the annual value of 13 MFPs gathered from just seven states stands at Rs3,802 crores. Tribal people constitute 8.6% of India’s total population, and 11% of the country’s rural population. It is estimated that directly or indirectly the livelihood of at least 250 million people is dependent on forest products and its business.

The four-month period from March to June is the time when most of the MFPs are collected and purchased. This earning constitutes the majority of the annual income of tribal communities. The nationwide lockdown that began on March 25 was recently extended by the government of India until May 17 with some relaxations. Particularly after the government failed to provide employment to labourers under the schemes like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) during the lockdown period, the dependence of the tribal people on the sale of forest produce increased in this period.

Mongabay-India spoke to several stakeholders including forest dwellers, community leaders, traders, and government authorities in different states to assess the impact of coronavirus lockdown on the tribal communities. It is clear that while there are pockets where the collection and purchase of MFPs is underway, the lockdown has largely had an adverse impact on the lives of tribal communities.

The fear of exploitation

Masaram, a 45-year-old Gond tribal who lives in Kuakonda block of Dantewada district in Chhattisgarh, can’t sell his tamarind as the markets have remained closed during the lockdown. In such a scenario many of the forest dwellers are selling their products at a very cheap price to sustain them through this tough time.

After the lockdown was imposed, the union tribal affairs minister Arjun Munda wrote a letter to all chief ministers on April 6, asking them to initiate “proactive measures” for the well-being of the tribal population. Munda asked the states to act through Pradhan Mantri Van Dhan Yojana (PMVDY) to provide the tribal people safety and ensure their livelihood. Moreover, the government revised the minimum support price (MSP) of 49 MFPs.

“The increase across various items of minor forest produce ranges from 16% to 66%. The increase is expected to provide an immediate and much-needed momentum to the procurement of minor tribal produce in at least 20 States,” said an official statement of the government of India.

Despite this, people on the ground are grappling with many issues and for those who live in far-flung areas, it is impossible to get the price for their crop.

“The government rate of mahuwa is Rs30 per kilogram but there is no market and no traders. If you live near the roadside you can sell it for around Rs20-22 per kg (to local shopkeepers), but in the villages deeper in the jungle one can only barter (with some other product),” said Ranjana Kashyap, a Maria tribal who lives in Nakulnar village of Dantewada, Chhattisgarh.

Experts say that the most critical institutional support doesn’t exist for collection and procurement of the MFPs with immediate payment.

“The proposal for providing support through Van Dhan Vikas Kendras (VDVKs) would not help as so far there are only about 1,000 VDVKs. Most of these VDVKs are not fully functional. Similarly, the primary procurement agencies (PPAs) proposed earlier by Trifed for facilitating the implementation of MSP schemes have not been constituted in the states or are not functional,” said a report prepared by civil society organisations like the Campaign for Survival and Dignity (a national platform of forest dwellers groups), Kalpavriksh, and several other independent researchers working on the issues related the tribal communities and forest dwellers. The report was submitted to tribal affairs ministry on May 4.

The report also highlighted poor access of tribal and forest dwellers to the public distribution system (PDS) is being reported from across the states which is putting their food security in danger. “At this time, the PDS should be provided to all needy families and migrant workers including those who don’t have any cards. Provision of ration, vegetables, cooking oil, and other essentials should be made available at their doorstep,” said the report.

It demanded that special attention must be given to ensuring that single women and women-headed households are covered under MGNREGA. The report also said that the union tribal affairs ministry should constitute a Covid-19 Response Cell with a team of designated nodal officers to coordinate with state governments (and their tribal departments) and civil society organisations to monitor issues of tribal people and forest dwellers and provide the necessary support.

For tribal people and forest dwellers living in the wildlife sanctuaries, national parks and tiger reserves, the report said that they have been facing problems in exercising their livelihoods rights. “The ministry of tribal affairs should request the environment ministry to modify the advisory on protected areas to ensure that rights and livelihoods activities of communities living in protected areas are not restricted due to the lockdown and to ensure the communities be provided with food, income, and other essentials,” said the report.

The government officials say it will take time to assess the impact of lockdown on the tribal economy. “No doubt this year the trade is down 30-40% in comparison to last year,” said Swayam Mallik, divisional forest officer of Baripada division of Mayurbhanj district in Odisha. “Traders are restricted within the districts and they are holding the stock (in that area). Some of these items are not perishable. So, after the lockdown is relaxed or eased, they can move and sell it. We hope things will start turning normal.”

Backbone of the tribal economy

Tendupatta or tendu leaf, often called the golden leaf, is the most prominent forest product and has the highest revenue-generating potential. It is mainly used to wrap tobacco and manufacture bidi (a form of cigarette). Besides sale in the domestic market, tendu leaf is also exported to several countries including Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia.

As per the data provided by the ministry of tribal affairs, the estimated annual value of tendu leaf is Rs1,000 crore, but given the modest procurement by the government, this value seems very low.

More than 90% of total tendu leaf procurement happens in just five states—Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Maharashtra, and Andhra Pradesh. According to a report by Indira Gandhi National Forest Academy, Dehradun, every year almost 200,000 tons of tendu leaf is procured from Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, which is more than 50% of the total procurement.

With the extension of the lockdown in India, the business of tendu leaf may suffer this year. However, the state governments claim that they are “alert” and have a “plan” ready to deal with the situation.

“We have declared a minimum support price of Rs4,000 per manak bora (a standard unit of 45 kg) for tendu leaf. No other state is offering this price. Amidst the Covid-19 problem, we are also following the safety norms strictly. All labourers coming from outside of our state are going through a coronavirus test before they enter here for work,” said Bhupesh Baghel, chief minister of Chhattisgarh.

Another important issue during this lockdown is the high rate of goods and services tax on tendu leaf. Activists say that while the GST on all other MFPs is 5%, it is 18% on tendu leaf. If the government reduces or exempts the tax this year, traders may pass some of the benefits to the tribal people.

“These products provide income to the poorest of poor families living in and around forested landscapes of India, of whom scheduled tribes constitute the majority. The lockdown has not only affected rural communities but also traders who deal in these items. In order to bring back normalcy in the rural economy, the central government should bring down the GST rates to zero on forest products for the time being. Zero down of GST would encourage their trade, which would give a fair return to the poor forest-dependent families,” said Rao.

Social distancing in the forest

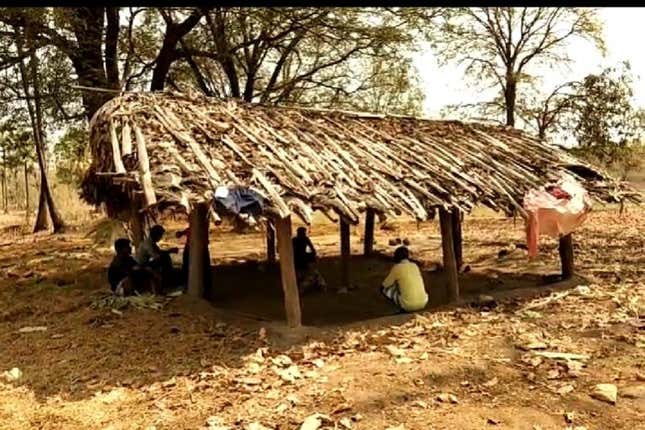

During the lockdown, the tribal people have shown remarkable prudence and sagacity by maintaining the physical distance while collecting the forest produce. In most of the places, they have followed the instructions and guidelines issued by the local administration.

On April 3, the Trifed had also issued a list of dos and don’ts while collecting MFPs. Besides asking people to keep distance while collecting forest products, it advised hygiene and use of hand sanitisers while working at collection and processing centres.

“Only one person is allowed to climb on the tree during collection. Even while processing the products, we are maintaining the distance. All men and women are asked to clean hands properly before and after the work,” said Lalbihari, a Khanti tribal who lives in Manika block of Latehar in Jharkhand.

In many places, the tribal people have blocked the entry points and did not allow any outsiders to come in. In the villages of south Bastar in Chhattisgarh, the people who returned from Telangana after the business of chilli plucking were asked to stay at the borders of the state for 14 days. Villagers arranged for their food and shelter but did not allow them to enter before they completed the quarantine period.

“In local tribal markets, the cock-fight is so common where many people gather at one place. But you know, during this lockdown, perhaps for the first time in history no cock-fight happened anywhere in Bastar. The villagers even had put banners at the boundary of their villages and denied entry to any outsider. It shows that they are as aware and concerned about this disease as those who live in the urban areas,” said chief minister Baghel.

This post first appeared on Mongabay-India. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.