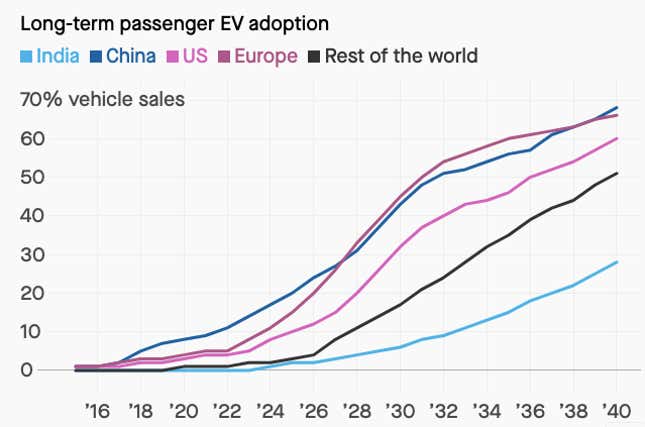

Last year, the Narendra Modi government announced plans to achieve electric-vehicle penetration of 30% of all vehicles sold in India by 2030. Little did it know that a pandemic outbreak would soon bring its entire economy to a standstill.

Several industry experts now say that coronavirus has put the brakes on the sector for the short term, and most likely for the medium term as well—established players will focus on conventional vehicles, while new players will be stuck for capital.

“Owing to weak demand amid the Covid-19 outbreak, capital expenditure and investment plans towards electrification of vehicles in India will be deferred by 12-18 months,” Subrata Ray, senior group vice-president at credit agency ICRA, told Quartz, adding that internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles “will continue to account for the bulk of sales.”

Not just coronavirus pain

Even before the coronavirus outbreak, the EV segment in India was a roller-coaster ride with a few highs and many lows.

For starters, the government flip-flopped over its EV goals—initially announcing in 2017 that India would switch to 100% electrification of vehicles by 2030, and then dialing back those ambitions, which led to delays in clarifying its plans for incentives for the industry. Yet experts felt the revised goal wasn’t realistic either, because the issues that plague EVs everywhere—price and charging anxiety—are even more intense in India.

“EV prices remain significantly higher than their ICE counterparts, which along with limited range and lack of public charging infrastructure resulted in minimal EV penetration in the country,” said Ray, which expects their share of sales in the next five years to be no more than 3-5%.

While electric vehicle sales in India were up 20% in the financial year ended March—compared with a nearly 18% decline for regular vehicle sales—the already tiny figures for EV passenger cars declined. Even the roughly 150,000 electric two-wheelers sold account for less than 1% of sales in that category. (The EV sales figures don’t include the popular e-rickshaw category, a more informal sector whose numbers are hard to capture.)

The entire Indian passenger car industry saw sales plummet after the government imposed a strict lockdown in late March, but electric passenger vehicles are set to be “disproportionately affected” by dampened demand, explained Aarti Khosla, director of Climate Trends, a Delhi-based firm focusing on issues of clean energy.

“(The) average Indian customer views the car as a mature investment, and so has to be convinced of its ease of maintenance and resale value, and a traditional internal combustion engine vehicle provides that,” Khosla told Quartz. “After-sales convenience with a novel technology such as EVs is yet to be adequately visible.”

The current crisis is piling more pain on top of those challenges by crippling the sector’s financing, which depends heavily on investors since sales are still so small. Several member startups of the industry body Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles (SMEV) shut their businesses due to cash flow problems in recent months, Sohinder Gill, director-general of SMEV and global CEO of Hero Electric, told a recent conference by ETAuto.

Other manufacturers concur that hard times lie ahead.

“The scale in EV demand will come only when we have a domestic battery-making industry and a well established charging/swapping network. Due to coronavirus, there is financial stress on companies, and investments would be hard to come by in the short term,” said Deb Mukherji, managing director of Omega Seiki Mobility Pvt. Ltd., a New Delhi-based EV startup firm that provides electric three-wheelers to global e-commerce companies for deliveries. Players reliant on Chinese imports will also face disruptions, he added.

At present, India is heavily dependent on China for EV components. In the financial year ended March 2018, Chinese EV exports to India touched $4.3 billion, up 27% over five years. But Chinese factories didn’t reopen as usual after the Chinese New Year holiday that fell in late January, as Beijing imposed lockdowns to contain an outbreak that was soon to become a global pandemic.

Delivering hope

Even with these challenges, experts see specific types of demand growing—especially those linked to e-commerce, which has done well during India’s rolling lockdowns.

“There are two reasons for this: One is the e-commerce industry using a lot of these EVs for last-mile drops. The second reason is to focus on health, hygiene and environment in the post-Covid-19 world, which will drive the EV industry and the focus will be on two-wheelers and three-wheelers,” said Mukherji.

That would mimic the pattern in China, the world’s biggest maker and buyer of electric vehicles, where two-wheeled EVs supplying online deliveries paved the way for wider adoption. For instance, Walmart-controlled e-commerce giant Flipkart has been adding electric vehicles to its delivery network, with a goal of covering 40% of its last-mile fleet this year.

The trade disruptions of this year could also help boost local supply chains for the industry, Mukherji believes. “Companies that are focusing on developing and producing vehicles indigenously will continue and may even get a stronger push… We will see serious players with the domestic supply chain successfully launching their products,” he said.

Those suppliers could take some time to materialize, however.

“At present, in India, localisation content in electric-vehicles is fairly low,” said Ray, of ICRA, adding that it takes substantial time for new products to come online. “But, with expected improvement in volume over the medium term, localisation content will gradually increase.”

Industry trackers will be looking closely at India’s early adopter states for signs of resilience. Gujarat, for example, has the highest number of high power lithium battery (pdf) electric two-wheelers sold through FAME, a central government program to boost demand. It is followed by Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Haryana, according to a 2019 report from the New Delhi-based sustainability think tank TERI.

“Provided the economy starts to recover, EV sales could improve. This is particularly for regions with heavy use of two-wheelers, such as Gujarat and parts of Maharashtra,” said Khosla of Climate Trends.

While Maharastra has been one of the hardest-hit states by the outbreak—it accounts for roughly 1 out of 3 coronavirus infections in India—Khosla believes that “if manufacturers and government collectively come with the right discounts and incentives, EV two-wheelers sales have the potential to grow post-Covid-19 as well.”

Rescue expectations

A lot of Covid-19 damage control could depend on how much the government steps up.

Last year, the government allotted Rs10,000 crore ($1.3 billion) for the next three years under its Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid &) Electric Vehicles (FAME) programme. The plan provides subsidies for manufacturers so they can discount vehicles for buyers, and is also supposed to deploy charging infrastructure in cities.

But the amount to subsidize demand for passengers cars over the next three years, for example, is only Rs525 crore ($70 million), which Ray said is too little “to provide any meaningful impetus to EV growth in the passenger car segment.”

Khosla suggests the government could offer corporate tax breaks or reimburse a percentage of their costs for switching. Additionally, the government could boost public visibility by deepening the use of EV in public transport. “(T)his is a chance to also ensure electric buses are given incentives and offer good quality public transport to those for whom buying a private vehicle is not a matter of choice,” Khosla said.

Last year in Maharashtra’s Pune, the authorities did adopt EV buses as a mode of public transport. But the rest of the country is still way behind. According to SMEV, the industry body, big commitments regarding EV buses made by various state governments did not translate into purchases.

Some think more subsidies will accomplish little—if India doesn’t quickly invest in and build the infrastructure electric vehicles need.

“These stimulus plans don’t fare well in the long-run because they don’t solve the underlying issue,” said Moran Price, co-founder and CEO of IRP Systems, an Israel-based manufacturer of EV components used in India. “The government would be wise to invest in EV charging infrastructure and sustainable technological innovations, both of which will make EVs more affordable for everyone.”